In honor of the departed

‘Day of the Dead’ celebration is expanding in the U.S.

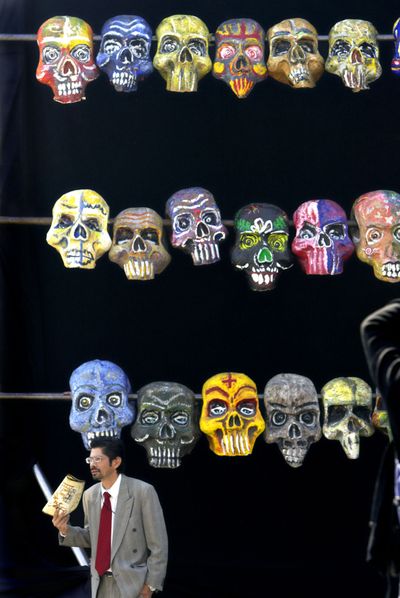

Still, Torres became fascinated by Day of the Dead folk art and ceremonies he saw during his father’s research trips to Mexico. Those images of dancing skeleton figurines and the event’s spiritual messages of honoring the dead, he says, were misunderstood in the United States.

“People here thought it was something to be scared of or evil,” says Torres.

But that’s changing. In the last decade or so, this traditional Latin American holiday has spread throughout the United States. Not only are U.S.-born Latinos adopting the Day of the Dead, but various underground and artistic non-Latino groups have begun to mark the Nov. 1-2 holidays through colorful celebrations, parades, exhibits and even bike rides and mixed martial arts fights.

In Houston, artists hold a “Day of the Dead Rock Stars” where they pay homage to departed singers like Joey Ramone, Johnny Cash and even “El Marvin Gaye.”

Community centers in Los Angeles build altars for rapper Tupac Shakur and Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

“It’s everywhere now,” says Carlos Hernandez, 49, a Houston-based artist who launched the “Day of the Dead Rock Stars” event. “You can even get Dia de los Muertos stuff at Wal-Mart.”

The Day of the Dead, or Dia de los Muertos, honors departed souls of loved ones who are welcomed back for a few intimate hours. The holiday is celebrated in Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil and parts of Ecuador.

Pre-Columbian in origin, many of the themes and rituals are mixtures of indigenous practices and Roman Catholicism.

At burial sites or intricately built altars, photos of loved ones are centered on skeleton figurines, bright decorations, candles, candy and other offerings such as the favorite foods of the departed.

Leading up to the day, bakers make sugar skulls and sweet “bread of the dead,” and artists create elaborate paper cut-out designs that can be hung on altars. Some families keep private night-long vigils at burial sites.

In North America, decorations often center on images of La Calavera Catrina, a skeleton of an upper-class woman whose image was made popular by the late-Mexican printmaker Jose Guadalupe Posada.

She is typically seen on photos or through papier-mache statues alongside other skeletal figures in everyday situations like playing soccer, dancing or getting married.

“She is our best-selling item,” said Torres, 35, who owns the Masks y Mas in Albuquerque, N.M., a shop that sells Day of the Dead art and clothing year-round. “I have artists sending me their Catrina pieces from all over.”

Albuquerque’s National Hispanic Cultural Center hosts an annual “Dia de los Muertos Community Gathering.” This year it is exhibiting an altar by Mexican-American novelist Sandra Cisneros dedicated to her mother.

The city also hosts an annual parade where marchers dress in Day of the Dead gear and makeup, and organizes a “Day of the Tread” bike and marathon race.

Events are not limited to the Southwest. Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology has a Day of the Dead altar on permanent display and offers Day of the Dead art classes to students in second to eighth grades.

And in New York City, the Brooklyn Arts Council recently initiated a year-long Day of the Dead education project to heighten public awareness “on mourning and remembrance.”

The growing Latin American population in the U.S. and the increasing influence of Hispanic culture here in everything from food to TV programming are obviously major factors in the growth of Day of the Dead celebrations.

But the holiday’s increased popularity may also coincide with evolving attitudes toward death, including a move away from private mourning to more public ways of honoring departed loved ones, whether through online tributes or sidewalk memorials.

“I think it has to do with Sept. 11,” says Albuquerque-based artist Kenny Chavez. “We’re all looking at death differently, and the Day of the Dead allows us to talk about it.”

He says those unfamiliar with the event sometimes freeze when they first see Day of the Dead images.

“We have people come into the shop and ask if this about the occult or devil worshipping,” says Chavez, who works at Masks y Mas. “They get all weirded out until you explain what this is.”

But as Day of the Dead grows in presence, some fear that the spiritual aspects of the holiday are being lost.

Already in Oaxaca, Mexico, where Day of the Dead is one of the most important holidays of the year, the area is annually overrun by U.S. and European tourists who crowd cemeteries to take photos of villagers praying at burial sites.

Art dealers buy cheap crafts, then resell them at much higher prices at chic shops in the U.S.

Oscar Lozoya, 57, an Albuquerque-based photographer who shoots fine art photographs of La Catrina, says some newcomers to the holiday are merely using it as an excuse to party and dress up in skeleton costumes. He hopes that they eventually do their research.

“I know what it means and its importance,” he says. “So I think the more people look beyond the art and learn about it, the more people will understand its real significance.”