Flansburg, one of WSU’s top receivers, is Hall of Fame bound

It’s Hall of Fame weekend at Washington State, or as it’s better known, story hour.

Doug Flansburg dials the clock back to 1964 when Bert Clark had taken over the Washington State football program, and the “two” in two-a-day practices stood for cruel and unusual. Except that two practices a day in the preseason weren’t enough for Bert, so he added a third.

Later on, after what he considered a poor effort in a game, Clark inched closer to the draconian. He introduced a leather strap to the proceedings, and had assistant John Nelson give players a thwack across the backside if he sensed a let-up.

And then he thwacked Larry Eilmes, the piledriver fullback with a legendary ferocity.

“Larry just took off his helmet,” Flansburg recalled, “walked off the field, got in his car and drove home to Spokane. So then the coaches have a meeting and draw straws to see who’s going to go bring him back. When another guy walks off, maybe they let him go. Not Larry.

“That’s when they decided the strap wasn’t such a good idea.”

A different time, right?

Wrong. It was downright Triassic.

But that sort of dichotomy becomes instant context for the celebration the Cougars have cooked up for Friday evening at the Davenport, when a whopping 31 “pioneers” – almost all pre-1970s figures – join WSU’s Athletic Hall of Fame. It’s athletic director Bill Moos’ leather strap, if you will – something to spur the hall up to speed from all those years when his predecessors didn’t bother with an induction.

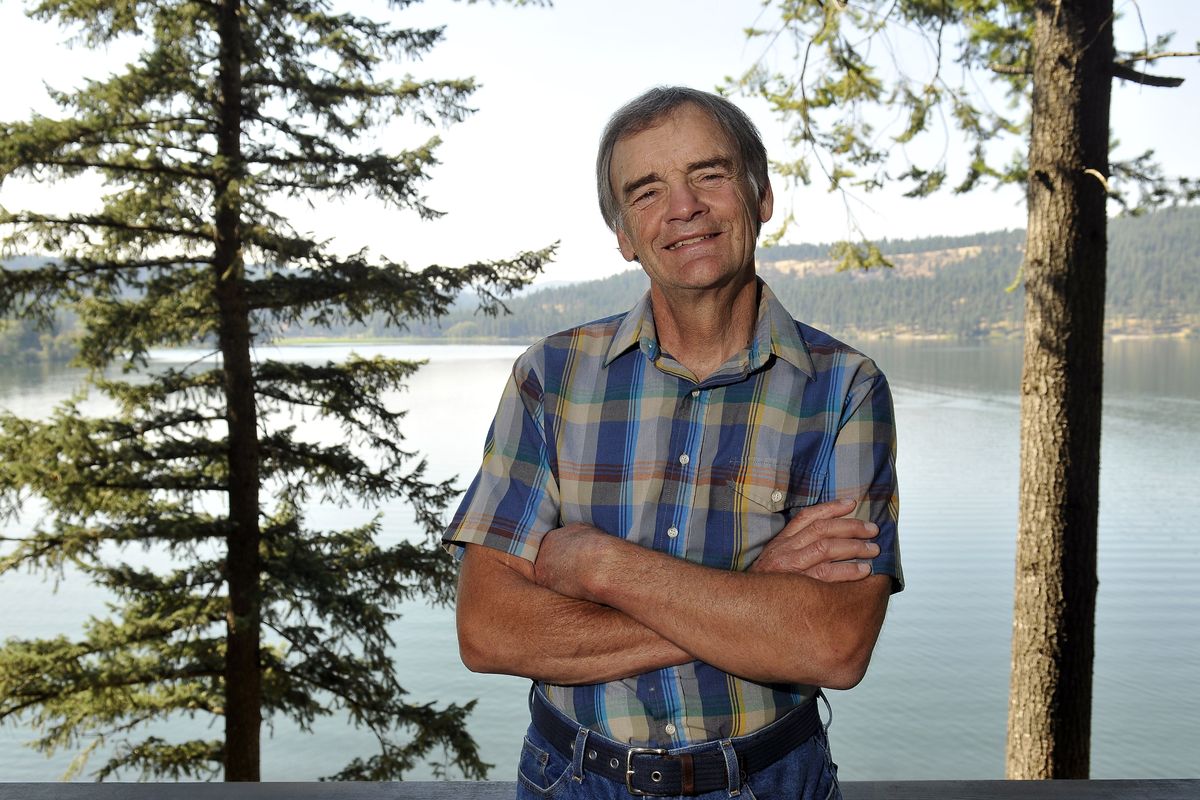

Still among Wazzu’s top 10 career receivers despite all the throwing the Cougs have done the past 35 years, Flansburg certainly fits in the what-took-them-so-long class. And when he found Moos’ letter in his mailbox out on Highway 27 south of Palouse, he spent the day in his shop telling his dog, Clancy, what a good deal it was.

“Somebody asked me if I expected it,” he said, “and I thought, well, I was probably eligible by the time I was 26 and I’m 66 now, so I figured I’d been passed over 40 times. No, I didn’t expect it. So I was tickled.”

And it’s only part of a good week. Harvest done on the 1,800 acres of wheat three generations of Flansburgs farm, he’s winding down at the family retreat on Lake Chatcolet where his grandfather built a cabin in 1935. Wheat prices “for the first time in my life” are high for a second straight year – $7 a bushel and change – and all the moisture produced the highest yields they’ve ever had.

Despite its teeter-totter nature, farming’s rewards endure. Flansburg watches his father, Allen, climb aboard a tractor at age 91 and can’t see himself backing off yet.

“Except when it’s 100 degrees and the combine breaks down and you’re out there trying to change a tire,” he laughed.

Valedictorian of the 15-student class of 1963 at Palouse High School – Flansburg knew he was destined for WSU 12 miles away, even though no one was going to give an athletic scholarship to a single-wing tailback from an 8-man team. He did get courtesy letters from basketball coach Marv Harshman and football assistant Rod Enos.

“I figured I’ll try football and if I don’t make it, I’ll try basketball,” he said. “And if I don’t make that, I’ll try baseball.”

He never got to Plan B. End Bud Norris wrecked his car and himself two weeks before practice began in 1965 and Flansburg stepped in, snagging 46 passes for the 7-3 “Cardiac Kids” who made incredible comebacks routine. He caught the touchdown pass against Indiana after time had expired – the Hoosiers had been flagged offsides – and the Cougs made the two-point conversion for a miraculous 8-7 win.

The graduation of Eilmes and key figures from a terrific defense, plus the toll of Clark’s spirit-crushing, put the program in reverse. But Flansburg still thrived, becoming All-Pac-8 as a junior and catching 12 balls in a loss to Houston – still WSU’s single-game record.

“But you have to realize Bert just wanted to run the ball,” he said. “I was the only split end in the offense.”

Befitting his talent, he was drafted after graduation – only by the Army. His year-long tour in Vietnam was as a chaplain’s assistant – “I had to carry a rifle, but not in a rice paddy” – and though he witnessed the worst, he also remembers small rays of light. He taught at a school outside the base at Phuc Vinh, and his old high school raised money and sent it off to buy his students books. The engineers at the base built sports fields for the children.

“You felt like you were doing something kind of good,” he said, “but hindsight makes it a lot clearer. I have a different opinion about the war now.”

That was the only year in the last 54 that Flansburg didn’t drive combine. Football seemed very far away when he returned, other than the fall Saturdays he’d find his way to Martin Stadium. Even those have become fewer – sometimes because “it takes me longer to get my work done,” and sometimes because, well, the results were making it worse to be there than to stay home.

And, yes, it’s different now.

“I don’t think a guy from Palouse can play for the Cougars anymore,” he said. “You have to be special to make those teams. I feel a little bad about that. There are so many kids who would have the same dream I did, but realistically, they don’t have much of a chance.”

Just another reason to get the ones who lived the dream into a place where the stories can be shared.