Family of man slain by deputies wants inquest

Granville Dodd was home in bed when he got the call.

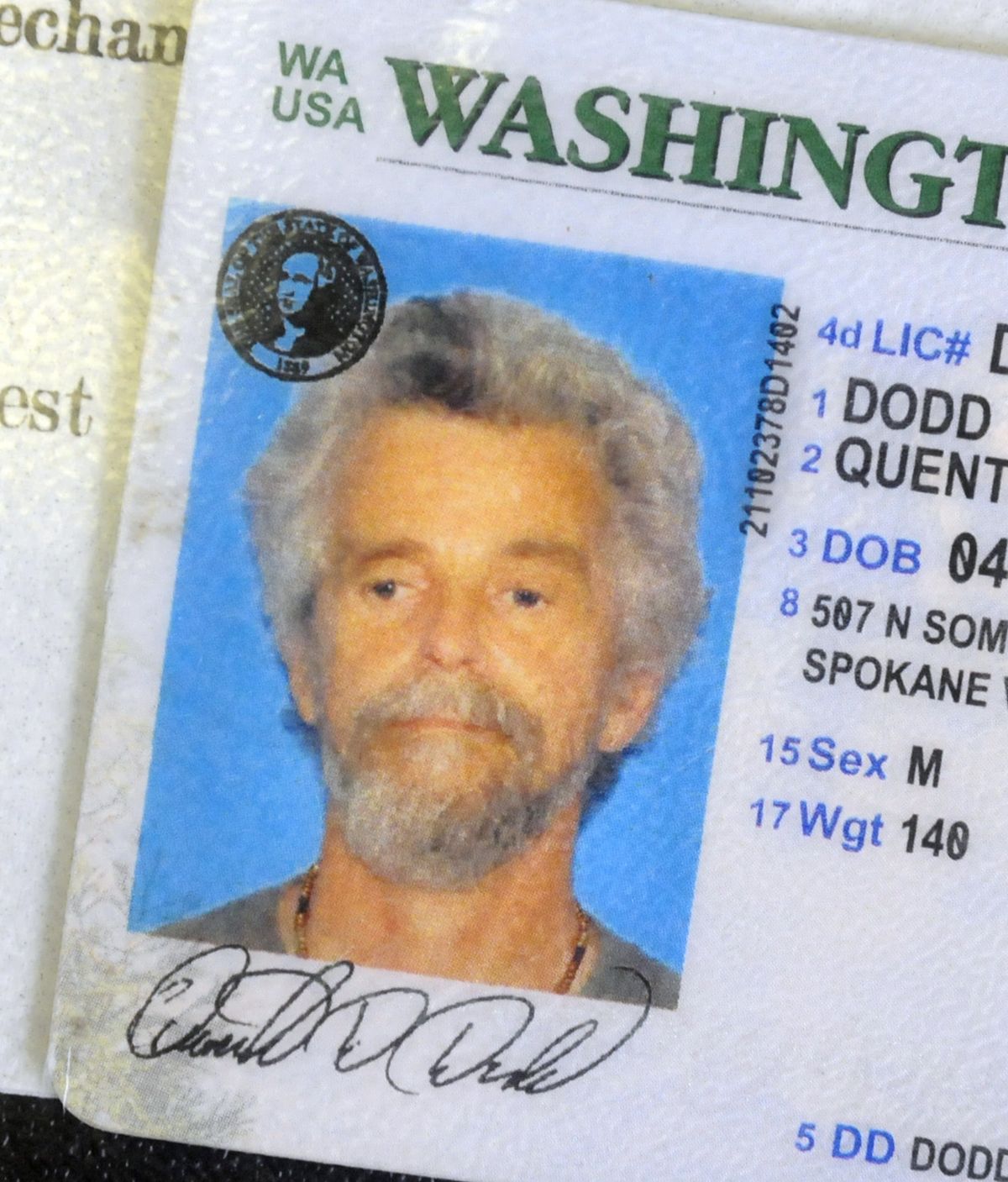

His younger brother, Quentin Dodd, one of 11 siblings, had been shot in Spokane Valley by a Spokane County sheriff’s deputy. It was bad, his family said, but no one knew exactly what happened.

Dodd soon learned his 50-year-old brother was dead. Nearly one year later, he says he’s still searching for answers to questions he has had since day one.

Granville Dodd questions the deputy’s account of the shooting, compared to the forensic evidence, and he’s troubled that police portrayed his brother as being high on drugs when an autopsy showed only prescription medication was in Quentin Dodd’s system.

Spokane County prosecutors recently ruled the Oct. 24, 2010, shooting by Deputy Rustin Olson was justified. Olson and another deputy who confronted Dodd that evening told investigators that Dodd wielded a sharp obsidian rock, refused orders to drop it, threatened to stab one of them, then ran toward Olson, prompting the deputy to shoot.

But the Dodd family, through their attorneys, Breean Beggs and Mark Harris, are calling for a closer examination of the case in the form of a jury inquest.

Beggs said a jury inquest – common in some jurisdictions but not conducted in Spokane County in the past 30 years – would help address what the family considers troubling questions.

“This is exactly why we need to have them,” Beggs said. “When the victim’s dead, the only witnesses are officers, and the forensic evidence doesn’t match at all – that’s when you need a jury to figure out what really happened.”

But law enforcement authorities and Spokane County Medical Examiner John Howard say it’s not necessary.

“We don’t do inquests on request,” Howard said. “They’re a tool – an ancient tool – to answer those questions which modern investigation has basically superseded.”

Chief Deputy Prosecutor Jack Driscoll, who reviewed Dodd’s death, said he believes he had enough information to assess the case. Witnesses told investigators that Dodd left the halfway house that evening holding the obsidian. That information was reported in a call to 911, then relayed to deputies, Driscoll said.

“Under the facts and circumstances, the officers were justified in their use of force, from the reports I was presented,” he said. “The critical factor is this person was asked repeatedly to drop the weapon. It’s verified through other witnesses that he had a weapon.”

Autopsy photos show the bullets Olson fired entered Dodd at a downward angle from the left side, including a shot to the left shoulder. Dodd’s family says the wounds don’t match Olson’s claim that Dodd was charging him head-on. But Driscoll said the shots entered Dodd’s body from the front, which is consistent with Olson’s version of events.

‘Like sitting ducks’

Quentin Dodd worked as a helicopter mechanic for the Army National Guard for nine years before working a variety of maintenance and mechanical jobs in Spokane. He had prior run-ins with police, including a reported suicide attempt on railroad tracks in Spokane Valley in July 2010.

He had completed a drug rehabilitation program and had been at the halfway house at 507 N. Sommer Road for about 2 ½ months. The residence’s owner said that Dodd had admitted using methamphetamine three days before the shooting and that Dodd had left the home that night after threatening another resident.

Two deputies were dispatched around 7:30 p.m. in response to the 911 call regarding Dodd’s behavior. They gave detailed statements to investigators on what they encountered that evening.

Olson said he “was a little nervous” when he first arrived at Progress Road and Valleyway Avenue, after Deputy Todd Miller spotted Dodd walking north from the halfway house.

Olson said he and Miller were “like sitting ducks” as they approached Dodd that day. They had heard witness reports, which Dodd’s family claim are in dispute, that Dodd was armed with a sharp obsidian rock. They weren’t sure if he also had a gun.

“And then I just figured, you know, regardless what it is, it needed to be contained so he didn’t walk into somebody’s house and kill somebody,” Olson told investigators.

In reply, Spokane police Detective Mark Burbridge, the lead investigator of the shooting, said, “Perfect,” according to interview transcripts.

Miller and Olson followed Dodd in their patrol cars, and Olson jumped out and commanded, “Police. Stop.” Dodd turned around and, using an obscenity, said he would stab Olson. He then ran toward Olson, according to the deputy’s account.

“It was pretty much a run across the street at me and so I hurried and drew my gun,” Olson recalled in his interview. He said he took three or four steps back and turned on the light on his handgun “so I could see better ’cause I could see something in his hand,” Olson said.

The deputy said he realized what it was and yelled “Drop the knife” repeatedly. Olson said Dodd turned “for a second” before he turned back around “and just started coming at me.”

Olson said Dodd raised his right arm and said either “I’ll … stab you” or “I’ll kill you.”

“I could see the knife in his right hand,” Olson said, describing it as a brown arrowhead knife without “the standard silver blade.”

“He never stopped, and that’s when I raised up and shot him three times in the chest,” Olson said.

In his interview, Miller said Dodd yelled “Shoot me” repeatedly when Miller first contacted him from his police car. Miller said he stopped his car and shined a spotlight on Dodd. At that moment, Dodd dropped the obsidian, then picked it up, yelled at Miller and continued walking, the deputy said. Miller and Olson continued to follow Dodd in their patrol cars, side by side in both lanes of Progress.

Miller said Dodd ran at Olson when Olson got out of his car. He said Olson yelled at Dodd “the whole time” to drop the knife and get down on the ground.

Burbridge asked Miller if he was concerned for Olson’s life.

“I wasn’t exactly sure how far he was going to let the guy go,” Miller responded, “because I felt comfortable where I was at from the guy.”

Miller said he was about 30 feet from Dodd, but “he was too close to Olson for my comfort.”

“Olson had his gun drawn on him and was giving verbal commands and I figured, when it was too close for him, then he would do what he had to do,” Miller said.

Miller said about 30 seconds elapsed between Olson getting out of his car and shooting Dodd.

Questions unanswered or unasked

The Dodd family, Beggs said, expected the prosecutor’s office to meet with them as the case was being reviewed, but that never happened, so they asked Beggs to conduct his own inquiry.

What Beggs found, he said, were troubling questions he doesn’t believe were posed, let alone answered, in the official investigation.

Beggs says the downward and leftward angle of bullet entrances on Dodd’s body don’t match Olson’s claim that Dodd was charging at him when the deputy fired his gun.

He and the Dodd family also question why investigators did not photograph Dodd’s key chain, which they believe he was holding instead of the rock.

Investigators say the obsidian was found two feet from Dodd’s body, but it was not photographed together with the body. In another photo taken at the scene, the key chain is seen from a distance but was not photographed up close. When Dodd’s family got the key chain back from police, a little plastic dagger that Dodd kept on it was missing, family members said. They later found it in Dodd’s room.

An autopsy showed Dodd tested positive for only the drugs he was prescribed to take. Despite the report Dodd had used methamphetamine three days earlier, no conclusive signs of illegal drugs were found in tests, according to the medical examiner’s office.

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich said he has never heard concerns from Dodd’s family about the shooting or the investigation.

Knezovich said the apparent angles of the bullets may not account for the position of Dodd’s body as he was charging Olson.

“In my experience bullets do a lot of different things when they hit a body,” he said. “Simple breathing can change the angle 5 degrees depending on whether you’re inhaling or exhaling.

“What you’re seeing in those (autopsy) photos is a body that was not in the position it was when he was shot,” Knezovich said.

Granville Dodd said he suspects his brother was irritated at deputies for trying to stop him and likely cussed at them and waved his keys. He believes his brother had the plastic dagger on his key chain at the time. So does Zachary Williams, Dodd’s roommate at the halfway house.

“I think it was just the key chain,” Williams told The Spokesman-Review. He said Dodd kept the rock as a collectible and didn’t often carry it. “I could have sworn I’d seen it in his room,” he said, adding that he doesn’t recall seeing it the day Dodd died.

Williams also said Dodd threatened him that day and accused him of pointing an airsoft rifle at him, which Williams denies.

The family, which has pored over the autopsy photos and report, believe the photos show signs that Dodd had been holding the key chain when he was shot. When they got the key chain back, one of the rings was damaged, as if something had been torn off of it, they maintain.

Beggs said Dennis Seymour, who reported to police that Dodd had thrown a can at him that day while holding a knife-like object, now says he didn’t see what Dodd had when he left the home. According to police, Seymour said Dodd went upstairs to his room for about five minutes before he left the house.

Seymour did not return a phone call seeking comment.

Differing views on aim of inquests

State law allows county medical examiners to call inquests, in which jurors consider autopsy results and police reports, and hear testimony from witnesses and people involved in fatal actions.

Typically, in an inquest of an officer-involved fatality, a deputy prosecutor directs the proceedings and an attorney for the family of the deceased may have the chance to cross-examine officers. The jury can decide whether the officers were justified in their actions or should face charges, but the decision is not binding on prosecutors.

King County conducts inquests for nearly every fatal police shooting under the direction of the county prosecutor and the county executive. Other jurisdictions, like Clark County, Nev., which includes Las Vegas, require inquests in every fatal police shooting. All are televised on the county’s public access station.

Knezovich said he wouldn’t object to an inquest but doesn’t think one is necessary.

“This thing’s been investigated by a regional team,” he said. “It’s gone through the prosecutor’s office, and the medical examiner has looked at it.”

Howard, the county medical examiner, said an inquest wouldn’t answer questions other than basic facts such as who was killed, where they were killed and who killed them. “Those questions have already been answered,” he said.

Beggs points to an inquest held in King County in January regarding the fatal shooting of woodcarver John T. Williams by Seattle police Officer Ian Birk, on Aug. 30, 2010. A jury of eight was tasked with answering two key questions: Did Birk believe Williams posed a threat, and did Williams pose an actual threat? Four jurors found that Birk believed he was being threatened, while the other four answered “unknown.” Four concluded there was no actual threat, one said there was and three others answered “unknown.” Birk was not charged in the shooting but has resigned.

Washington law states that the intent of an inquest is to determine a cause of death, but Beggs said inquests aren’t limited to certain questions. “(Howard’s) office has sort of taken this narrower approach, but that’s not how it’s been used in Washington.”