Stepping into the light

Implanted scope can restore sight for those with macular degeneration

People suffering from severe age-related macular degeneration, one of the leading causes of blindness in older adults, will soon have a way of seeing again – with a tiny telescope implanted in their eye.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved the CentraSight telescope for people 75 and older who have not had their cataracts taken out and have end-stage macular degeneration, the most advanced form of the disease where there is permanent scarring in the eye.

The FDA based its approval of VisionCare’s telescope on results of a clinical trial that included Marian Orr of Charlotte, N.C.

Orr was one of 19 patients to receive the telescope seven years ago at Charlotte Eye Ear Nose and Throat Associates. The Charlotte practice was the only one in the state to participate in the clinical trial in 2003.

Medicare still has to review and approve the device for coverage, which could take a few months. The cost for screening, surgery, rehabilitation and the device is about $20,000.

Orr, now 80, was diagnosed with macular degeneration in 2001, when the center of her vision became progressively blurrier and darker until much of her eyesight was blocked out.

“My dad and his brother were blind in their later years and I didn’t want to be like that,” Orr said. With the implanted telescope, she can watch TV and read books.

Age-related macular degeneration affects about 8 million people in the U.S., significantly impairs vision for 2 million, and occurs most commonly in people 60 and older.

The eye telescope is the only implantable device to improve vision for those with end-stage macular degeneration. Laser surgery, light-activated medicine and eye injections can also be used to treat advanced macular degeneration.

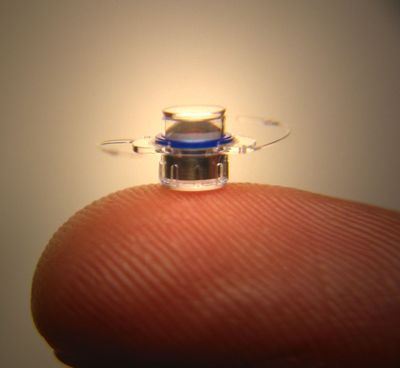

The telescope, smaller than a pea, works by allowing light to be focused on working parts of the retina. That helps restore the ability to see what had been previously lost, said Dr. Don Stewart, Orr’s ophthalmologist at Charlotte Eye Ear Nose and Throat. He implanted her telescope.

“Anyone can walk around with an external hand-held telescope, but that’s not very convenient,” he said. “But if it’s inside the eye, it’s really life-changing for people.”

Once implanted, the telescope is unnoticeable. There are two models: one that magnifies vision by 2.2 times, and another that magnifies by 2.7 times.

To implant the device, doctors remove the cataract from the eye. Then the telescope is put into the support structure of the eye’s lens, called the lens capsule, so it sits where the cataract was, said Dr. Kathryn Colby, an ophthalmic surgeon in Boston. She was one of the principal investigators for the clinical study that Orr participated in.

Though the telescope doesn’t heal anything, it uses other parts of the retina to partially restore central vision – the ability to see fine detail.

“Someone with end-stage macular degeneration might have a hole in their vision,” Colby said, “but with the telescope, we enlarge the image of the face so maybe you’re just missing the nose or part of the mouth.”

People who receive the implants have to go through rehabilitation to train one eye – the one with the implant – to see centrally and the other eye to see peripherally, Colby said.

Because of the telescope, Orr can see the most important things in her life – her family.

“My grandson once came to me and said, ‘Grandma, feel my face so you know who I am,’ ” she said. “And I said, ‘Now I don’t have to anymore.’ ”