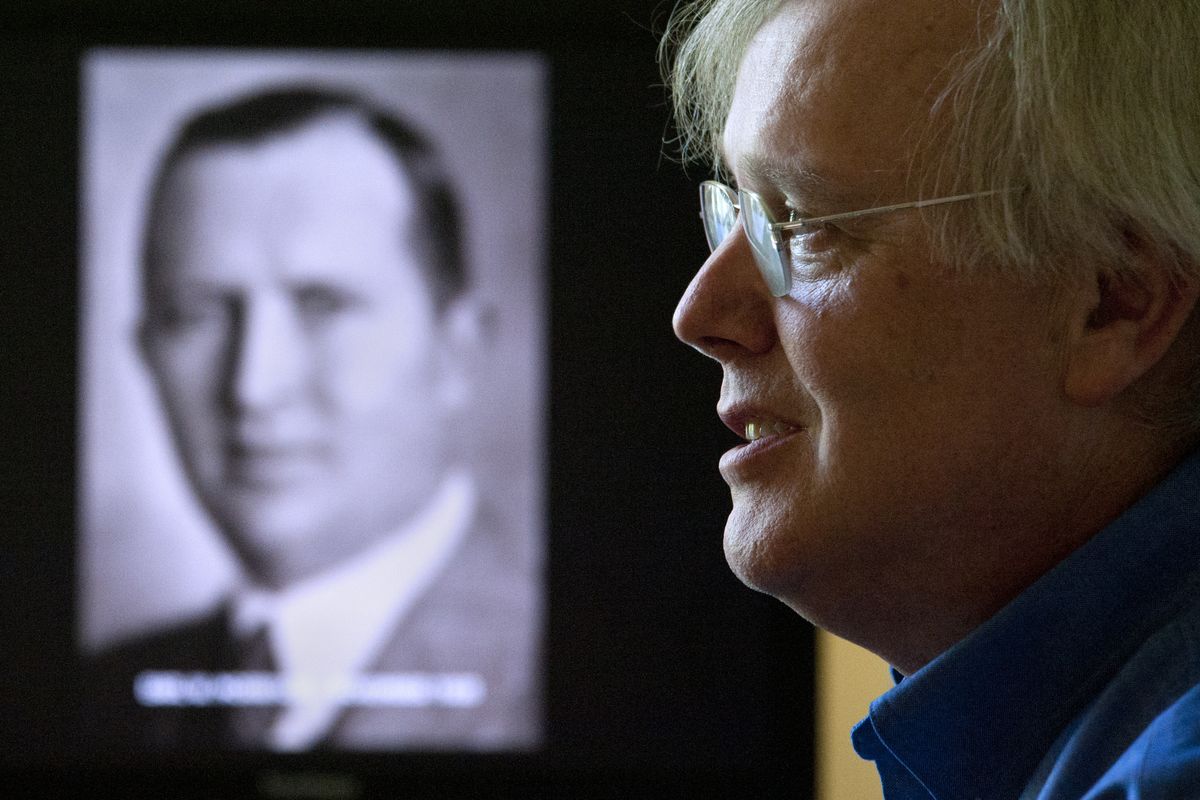

Admirer unearths memory of young architectural genius

Four years ago, Spokane architect Glenn Davis took a job renovating a historic South Hill home.

It was a beautiful Rockwood Boulevard home, built in 1912 in the Prairie style of Frank Lloyd Wright. As Davis delved into the restoration of the home, known as the David and Edith Ackermann house, he was impressed by the sophistication of the design.

“Everything just worked beautifully and fit together nicely and was done with quite a bit of restraint, which is a real rare thing,” Davis said.

Davis was surprised to discover that the architect had designed the home at the age of 23. It was among many large, impressive South Hill homes that Spokane’s “boy architect” had designed as a high school and college student.

And Davis, a man who knows a lot about Spokane’s architectural history, had never heard of him.

•

In the early 1900s, the lower South Hill and Rockwood Boulevard were being developed as the neighborhoods of choice for Spokane’s wealthy families. The Rockwood neighborhood was designed to follow the curve and sweep of the landscape, to provide access to street cars and to reflect a treed, green, park-rich environment.

The city was booming, and the swells – the bank presidents, the businessmen, the railroad bosses – were buying the mansions of their day. The homes were often built on spec, and the newspapers reported on them as they went up and when they were purchased.

A lot of those homes were designed by Earl W. Morrison.

Morrison was a professional architect before he finished high school at 22, having also worked as an electrician and a “helper” in a construction company. He had an office in his father’s suite in the Paulsen Building by the time he graduated in 1910. The exact path that led such a young man to design homes for the city’s most successful people isn’t entirely clear, but he seems to have forged relationships with key builders and businesspeople early, in part through his father, and earned their faith in his abilities, according to a history of Morrison that Davis has compiled.

By the end of 1910, at least 14 homes that Morrison had designed had been built and purchased by some of the city’s biggest names. Martin and Edwidge Woldson. Matt and Mamie Baumgartner. Edward J. and Helen Cannon.

By the time Morrison left to study in Chicago, he was locally famous. Within the next few years, his influence on Spokane’s South Hill architecture would only grow.

“It was a point of pride to say this was an Earl Morrison home,” Davis said.

Morrison studied under prominent architects at the combined Chicago Art Institute and Armour Institute of Technology. It was a time of change, of progress, of modernism in style, building materials and attitude.

Morrison, meanwhile, kept designing homes for Spokane’s South Hill at a torrid pace. In his exhaustive research into Morrison, Davis has identified some 18 designs that were built in his time in Chicago, and there are undoubtedly others.

“When I look at what he produced in college, I wonder how he had any time for classes,” Davis said.

•

The Ackermann house was one of those college designs. Built on spec, it was purchased by David Ackermann, a man who owned a café and bakery which was later sold to a conglomerate that bought up smaller bakeries and eventually developed Wonder Bread.

Davis worked on the restoration in 2008. When the time came to have the home designated for the Spokane historic register, Davis began to research Morrison more fully.

The more he tugged at that little bit of string – who was Earl Morrison? – the more another question grew in his mind. Why, given Morrison’s impact on Spokane and the state, didn’t people already know the answer?

•

Morrison returned from Chicago and opened an architectural office in Spokane. He continued building nice homes on the South Hill, but he had developed his craft and had begun to consider other ways he might use his skills.

The same year that the Ackerman home was built, Morrison’s first apartment building went up. The Oxford Apartments, which still stand at 702 S. Bernard St., reflected several Morrison hallmarks: high-quality materials and craftsmanship, careful use of attractive detail on a simple design, a dramatic entryway.

“He became interested in not just wealthy people of means, but also what he could do for people of limited means,” Davis said.

Also in 1912, Morrison designed a grand new vision for Cheney Normal School, complete with a glass dome and grand rotunda. It was never built, as it got caught up in political battles over state spending and education cutbacks.

Morrison enlisted in the Army Quartermaster Corps in 1917, designed a training camp in New Mexico and coordinated a supply station in France. He returned to a dismal Spokane economy two years later. A recession and then a depression followed the war, and Spokane’s population plummeted.

Morrison looked westward, opening a satellite office in Wenatchee, where fruit agriculture was booming. In 1921 and 1922, he designed fruit warehouses, a pool hall, a school, a church, another school, several homes – almost all in Wenatchee.

He was beginning to show the versatility and range that would come to mark the rest of his career. And, like so many of Spokane’s talented young people through history, he was edging away from his hometown.

Saturday: The boy architect puts his stamp all over the state.