Bin Laden was angry, alone

Letters show al-Qaida founder frustrated near the end

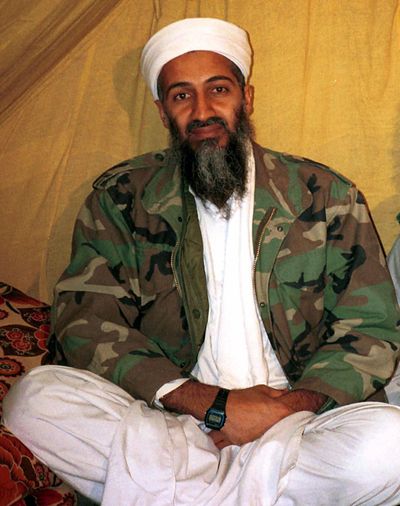

WASHINGTON – Seventeen letters seized from Osama bin Laden’s Pakistani hideout by the Navy SEALs who found and killed him there last May expose the international terrorist icon in his final years as increasingly irrelevant to his own movement.

The selection of letters – written between 2006 and April 2011 and released Thursday by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point – show bin Laden to be frustrated by the actions of the al-Qaida affiliates that had cropped up around the world and claimed the mantle of the organization he’d founded. With al-Qaida’s central organization largely destroyed, and what was left harried and in hiding, the letters indicate that bin Laden and his inner circle were unable to direct the activities of a network of affiliates – from Pakistan to Yemen to Algeria – over which he apparently had little or no control.

During bin Laden’s final years, as American and NATO forces focused the war on terrorism on breaking apart al-Qaida’s ability to operate from Afghanistan and Pakistan, the terrorist leader was dashing off letters that were highly critical of the affiliates’ operations, particularly those that resulted in the deaths of Muslims, and making calls for attacks that appear to have been ignored. Among them, bin Laden called for assassinating President Barack Obama – which he said would leave a “totally unprepared” Vice President Joe Biden to assume power – and Gen. David Petraeus, who was then the head of U.S. Central Command, which had responsibility for Afghanistan, by targeting their planes when they visited Afghanistan or Pakistan. It was unclear whether those plans were ever put into motion.

The Combating Terrorism Center, a privately funded research center at the West Point military academy, said that only these 17 letters out of reportedly thousands of documents seized from bin Laden’s compound had been declassified. Still, even that small sample, released a year and a day after bin Laden’s death, reignited debate among terrorism experts over the al-Qaida leader’s importance.

Magnus Ranstorp, the research director at the Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies at the Swedish National Defense College, said evidence of a neutered, irrelevant bin Laden should cause some concern over U.S. counterterrorism policy, much of which has focused on breaking apart a network that wasn’t functioning – and may never have functioned.

“We like to create frameworks and structure, even when sometimes there isn’t any structure,” Ranstorp said.

However, Daniel Byman, a terrorism expert at the Brookings Institution’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy, argued that counterterrorism efforts themselves had rendered bin Laden irrelevant. The intense hunt for al-Qaida central, he said, including the campaign of drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal areas, killed many militants, forced others into hiding and disrupted communications networks.

Still, Byman said, the letters imply that bin Laden had become a sort of modern-day Dr. Frankenstein in his last years. “He knew the monster was out there ravaging; he just wanted it to stop ravaging local villages and to go abroad,” he said. “He didn’t have that level of control.”

The Combating Terrorism Center’s analysis of the letters said that “bin Laden was burdened by what he viewed as the incompetence of the ‘affiliates,’ including their lack of political acumen to win public support, their media campaigns and their poorly planned operations which resulted in the unnecessary deaths of thousands of Muslims.” An apparently frustrated bin Laden wrote in May 2010 that such killings were eroding al-Qaida’s support and he urged that all attacks be aimed at the United States or U.S. interests overseas.

He wrote that in the case of such attacks, the perpetrators should “apologize for these errors and be held responsible.”

The letters cover a wide range of issues and hint at discord between bin Laden and other senior al-Qaida leadership. In one, bin Laden politely refuses an offer to make a direct public link to Somalia’s al-Shabab militant group, noting that such a connection would only bring more intense U.S. attention, might chase away relief and charity efforts in the area and might discourage the investment needed to build a solid economy in the poor nation.

In another, bin Laden delivers advice to Jaish al-Islam, a militant group in the Gaza Strip, which asked whether it was acceptable to take money from Iran and Shiite Muslim groups. (Bin Laden is Sunni.) Bin Laden replied that “accepting these monies for the sake of using it to conduct jihad and to strike the Jews is better than abandoning the jihad due to paucity of funds. So take it, if there is no other way, and strike the Jews. … And aim well!”