Landers: new steelheading book a matter of facts

A wise angler will shut up and listen to anyone with 30 years of steelhead fishing experience.

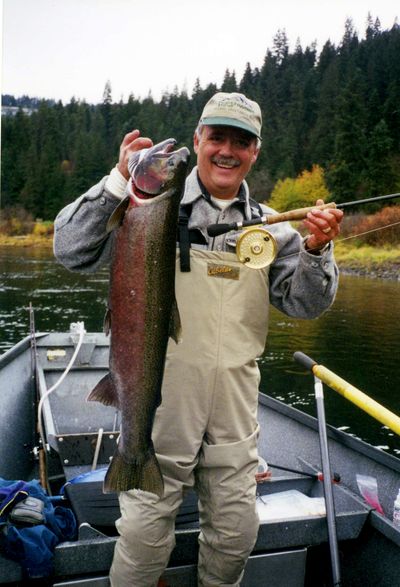

In the case of Dan Magers, steelheaders should go further, forking over $25 and devoting a few evenings to serious study of his new book.

Magers has backed his steelheading savvy with detailed records of Idaho’s Clearwater River. The information will boost the probability of catching steelhead in varying conditions in any river using any method, he said.

Magers, co-founder of Idaho Steelhead & Salmon Unlimited, has been rubbing elbows with experts on steelhead biology, politics and fishing for decades. What Magers has recorded has been debated, analyzed and, just recently, organized and published in “Striking Steelhead,” by Frank Amato Publications.

Thanks to a computer-literate daughter, Magers’ 18,000 nuggets of data were compiled in spreadsheets to draw out enlightening trends and percentages based on 18 of the 22 years he’s fished the Clearwater from his driftboat.

He filled out a log sheet each day after returning from the river. He usually annotated the report with information from guides who were working the river the same day.

“Like most steelheaders, I tried just about every technique,” he said. “Eventually, I found back-trolling lures from a drift boat to be the most exciting for me.”

The data are based on that technique, but he casts no aspersions on whether other methods are as good, better or more fun.

More important than the method is checking river flows and temperatures, knowing steelhead migration habits, having a working knowledge of river hydraulics and fishing accordingly.

“The most successful steelhead anglers change the type of water they fish and the tactics to fit the flows and temperature regardless of their preferred method,” he said.

Over 22 years, he’s logged 1,261 steelhead caught in his boat, for an overall average of 1.61 hours per fish.

Nevertheless, he said he knows a handful of Clearwater professionals who are even more successful because they’ve had to learn how to change techniques to put their clients into fish regardless of the conditions.

“I fish only the better conditions,” he said.

On the days that flows run too high in November, he simply doesn’t fish. He goes on to more productive use of his time, such as getting all of his business in order so he can hit the water as soon as conditions are right.

The book touches on the history of steelhead that make the 400- to 500-mile run from the ocean to Idaho waters each year. It sorts out the A-run from the B-run fish headed to the Clearwater, and distinguishes wild fish from hatchery fish.

He admits he has a preference for wild fish, which guides where he devotes most of this fishing time.

The perfect steelhead, he suggests, is “a 32-plus-inch wild steelhead that is in the air instantly upon hook-up, jumps three or more times, makes a couple reel-screaming runs across or up-river, comes unhooked just as it gets to the boat and darts away.”

Mostly, the book is about catching more steelhead, wild and hatchery fish alike.

Water temperature, he says, is almost everything, offering documentation to show that steelhead are happiest in 45-55 degree water. He notes they’ll travel farther to hit a lure in the upper reaches of that range.

He also demonstrates how fish shut down after a rapid decrease in water temperature.

Where you fish in the river is another major factor. The book illustrates the river structures that have produced the bulk of Magers’ fish with a discussion of bottom and edges, boulders, points, tailouts, slots and channels, ledges and eddies.

“Structures create hydraulics that pause upriver movement of migrating fish,” he said. “What type of hydraulics they favor is temperature dependent. Flow fluctuations change the hydraulics of all structures.”

Learning to adjust is the secret, he said:

“Ninety percent (of steelheaders) do the same thing every trip to the river, fishing the same way in the same place or same type of water. Then when the conditions finally line up with their method, they say ‘the fish were biting that day.’”

River flow is a bigger issue for the angler than the fish. Magers notes that his “60 best days” in the upper Clearwater are in flow ranges of 2,500-3,900 cfs, with a slightly narrower window in the lower river.

Other data trends help an angler decide whether to use bait (especially effective in colder temperatures), what colors to use and when to anchor for lunch with lures out (around noon to 1 p.m.).

He details drift-fishing sections of the river and instructs anglers on making a plan to improve their success.

A summary of conditions during Magers’ “60 best days” of steelheading on the Clearwater is compelling: 31 of the days were in October, 15 were in November, nine in September and five in December.

On the average during these 60 top trips his boat hooked a fish every 45 minutes; the average water temperature was 47 degrees, the average flow was 3,967 cfs.

“If somebody had given me this book and this data 30 years ago I can’t tell you how much money and time I’d have saved,” Magers said.

Weather is not a major factor, and “it doesn’t matter how many fish are coming over the dam. In fact, it can be better when there are fewer fish coming upstream.”

“I’ve taken these principles and found they work on steelhead streams all over the region,” he said.

It’s a matter of fact, he said.