Obama to designate Chavez home as nat’l monument

KEENE, Calif. (AP) — Maria Ybarra’s trailer is one of two left on the property that for over two decades was home to Latino labor leader Cesar Chavez and farmworkers like Ybarra who made up his movement.

Today, the foothills of the Tehachapi mountains continue to house the United Farm Workers of America headquarters and memorials to Chavez, though farmworkers no longer live there.

On Monday, during a campaign swing through California, President Barack Obama will designate 105 acres of the property as a national monument within the National Park system — a move that could help shore up support from Hispanic and progressive voters before the election.

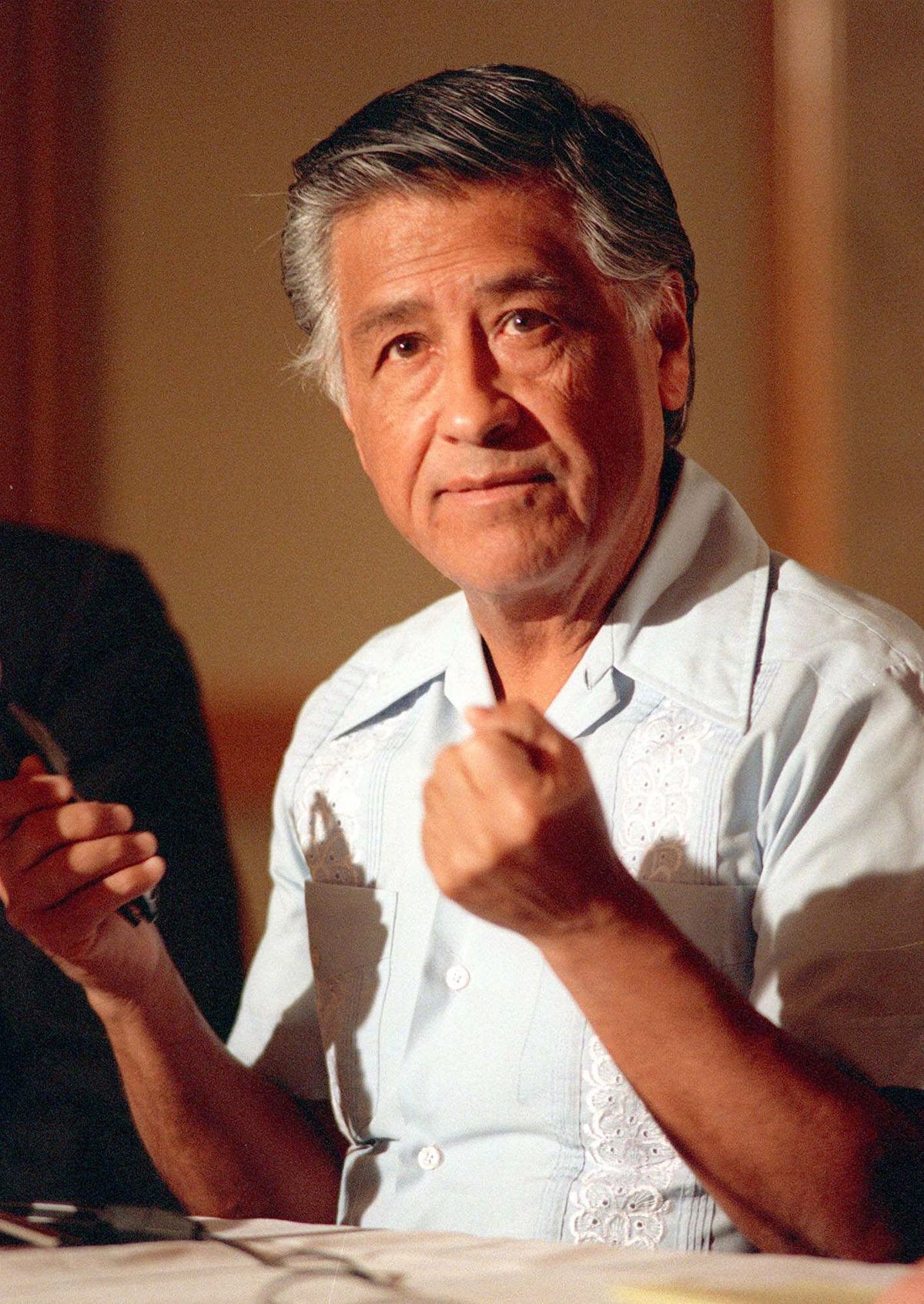

As head of the UFW, the Arizona-born Chavez staged a massive grape boycott and countless field strikes, and forced growers to sign contracts providing better pay and working conditions to the predominantly Latino farmworkers. He was credited with inspiring millions of other Latinos in their fight for more educational opportunities, better housing and more political power.

The 187-acre site, known as Nuestra Senora Reina de la Paz (Our Lady Queen of Peace), or simply La Paz, served as the planning and coordination center of the UFW starting in 1971. It’s where Chavez and many organizers lived, trained and strategized before heading into the fields and cities of California and beyond. Chavez taught farmworkers how to write contracts and negotiate with growers.

“When my father came to La Paz, he was looking for a place to pull back from the daily struggles,” said Paul Chavez, Cesar’s middle son and president of the Cesar Chavez Foundation. “He had a tremendous faith that with some training and confidence, the poorest and least educated among us could take on the biggest industry in the state.”

Ybarra still remembers those times and how Chavez’s movement coalesced around the property that she calls home.

Several hundred adults and children were housed at La Paz throughout the 1970s and 80s, Ybarra and her husband Miguel Ybarra among them, most in trailers on the hillside and in dorms. Kids played among the oak trees, while adults worked. “It was a lot of noise,” Ybarra said.

La Paz was a city unto itself: it had a Montessori school, a hospital, a legal department, a credit union, even a gas station. People worked as volunteers — paid symbolically $5 per week. There was a community kitchen and everyone ate together.

“It was fun, because we were working as a group,” said Ybarra, who first came to La Paz in 1973 and moved there permanently a few years later. “We were like a family. It was a lot of hard work, but Cesar motivated us.”

While Ybarra worked in the mail room and raised her children, her husband, now retired, was Chavez’s longtime personal driver.

After Chavez’s death in 1993, La Paz transformed. Volunteers started to get paid and most organizers moved out to towns and cities in the Central Valley, taking the sense of community and the noise with them. Ybarra, who still works in the mail room, and her husband were one of only two families that remained.

Union membership also declined, from more than 70,000 in the 1970s to what UFW officials say is about 27,000 today. That’s based on the number of people who work under union contract at least one day a year. However, the union has reported only about 5,000 members to the U.S. Department of Labor in each of the past eight Decembers, an admittedly slow month for farming.

Today, the La Paz property is quiet and peaceful, except for the regular sound of trains (the historic Tehachapi Loop is only a few miles away) and the occasional chatter of school children who come by the busloads to learn about Chavez’s movement. Lizards, squirrels and wild birds abound.

There are exhibits at the visitor center about the UFW and Chavez’s office has been carefully preserved. Visitors can also pay respects at Chavez’s grave site in the memorial garden and see the house where the farmworker leader lived with his family — his widow Helen Chavez still lives there. Those three sites will be part of the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument.

A conference and education center opened two years ago on the property in a converted historic building. It rents out halls, a theater, and a full service lounge for weddings, conferences and retreats.

The hope, Paul Chavez said, is that the center can go back to doing what Cesar Chavez once did: training regular people such as farmworkers, community leaders and activists in how to make change.

“If they can come here and we can give them some tools, and they can go back to their communities to use them, then I think my dad’s legacy has been served,” he said.

The national monument, which will be managed by the National Park Service, will bring more visitors to learn about the farmworker movement, Paul Chavez said.

The designation also will help diversify the offerings of the National Park System, said Tom Kiernan, president of the National Parks Conservation Association, an independent nonprofit that pushed to make the Chavez property the 398th site in the system.

“The whole purpose of the National Park System is to speak of what it means to be American and tell the stories of Americans,” he said. “The Latino culture and stories are not adequately told and interpreted throughout the park system, and this designation helps fill that void.”