Work underway to close abandoned North Idaho mine shaft

A special state fund derived from mining profits will be tapped to close a dangerous, publicly accessible abandoned mine shaft on private land in North Idaho.

But first, state and federal mine-safety experts say they will use a special “shaft cam” video device to find out what, if anything, has fallen down the Evolution Mine shaft and determine its exact depth.

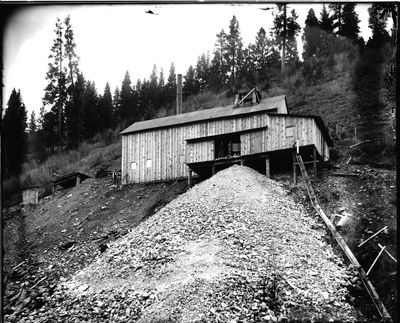

The vertical shaft, thought to be between 100 and 300 feet deep, is not marked or fenced. It has sat unattended for more than 60 years since mining operations ceased. The Evolution claim, filed in 1883, is the oldest in Shoshone County and very likely the oldest in Idaho, public records show. It was closed in the late 1940s.

“With all the time that’s past, what’s down that hole? That’s what people want to know before they close it up,” said historian and author Tony Bamonte, of Spokane, who was told about the abandoned mine shaft earlier this year by area residents Butch Jacobson and Fred Bardelli while researching a book about the mining district.

“It’s a bad situation up there, so this is real good news,” Jacobson said Wednesday when told efforts were underway to close the shaft he discovered as part of his hobby of visiting and documenting abandoned mining sites in the Idaho Panhandle.

Idaho Department of Lands mine safety experts visited the site 10 days after The Spokesman-Review published a story Sept. 20 detailing public safety concerns and the mystery surrounding the oldest mine site in the Panhandle.

The mine shaft is 475 feet from a frontage road on a steep hillside about 60 feet above Interstate 90. The opening measures 10.5 feet by 13 feet.

“It’s a big hole, easily accessible to the public,” said Eric Wilson, the Boise-based minerals program manager for the Idaho Department of Lands. Primarily for that reason, Wilson said, his agency is giving top priority to closing the shaft, mostly likely with a bat-friendly metal-mesh covering.

“Clearly, it’s very dangerous,” Wilson said after reviewing a report written by Jim Brady, a resources supervisor with the agency who inspected and photographed the site on Oct. 1 with Lauren Brunko.

In the inspection report, obtained under the Idaho public records act, Brady expressed surprise at how publicly accessible the site is and at its closeness to Interstate 90 near Osburn.

“It was way too accessible,” Brady wrote. “A good portion of my concern for this particular closing is the accessibility by the public. There is significant evidence the public uses the area just below for things such as paintball wars and target practice.”

The site is owned by the Coeur d’Alene Crescent Mining Co., which is owned and controlled by H.F. Magnuson & Co., of Wallace.

Dennis O’Brien, an executive with the Magnuson company, said he was unaware of the shaft’s existence. After reading the story in September, O’Brien said he made three attempts to locate the site before finding it.

“It is a big hole and it needs to be filled in or closed,” he said.

After the Department of Lands officials inspected the site, they contacted O’Brien and made him aware of a state fund created by the Idaho Mine Profits Tax. One-third of those taxes are set aside in a fund created a decade ago to pay for the closure of hazardous mine sites.

There are 440 identified sites on federal land alone in the Idaho Panhandle, and untold others on private property, according to officials with the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Emily Callihan, a spokeswoman for the Department of Lands, said the mining tax fund currently has about $7.1 million.

O’Brien signed an eligibility form giving the state the authority to develop and proceed with a closure plan that will be completely paid for through the state fund.

The state will seek bids from private contractors before the actual closure work occurs, likely early next spring, Wilson said. But before issuing requests for proposals, the state will have to fully identify the site and its location, including the depth of the shaft, and determine whether it provides bat habitat.

The Department of Lands doesn’t have equipment for video inspections, so the agency has contacted the federal Bureau of Land Management for that work. The federal agency has a special mine closure team based in Salmon, Idaho, which has agreed to assist, officials said.