First U.S. team to top Mount Everest reunites

Seattle man says his life changed

BERKELEY, Calif. – It might be hard to conceive now, in an era of extreme sports and ultra-light equipment, but there was a time when Americans who set out to conquer mountains engaged in a pursuit that was as lonely as it was dangerous.

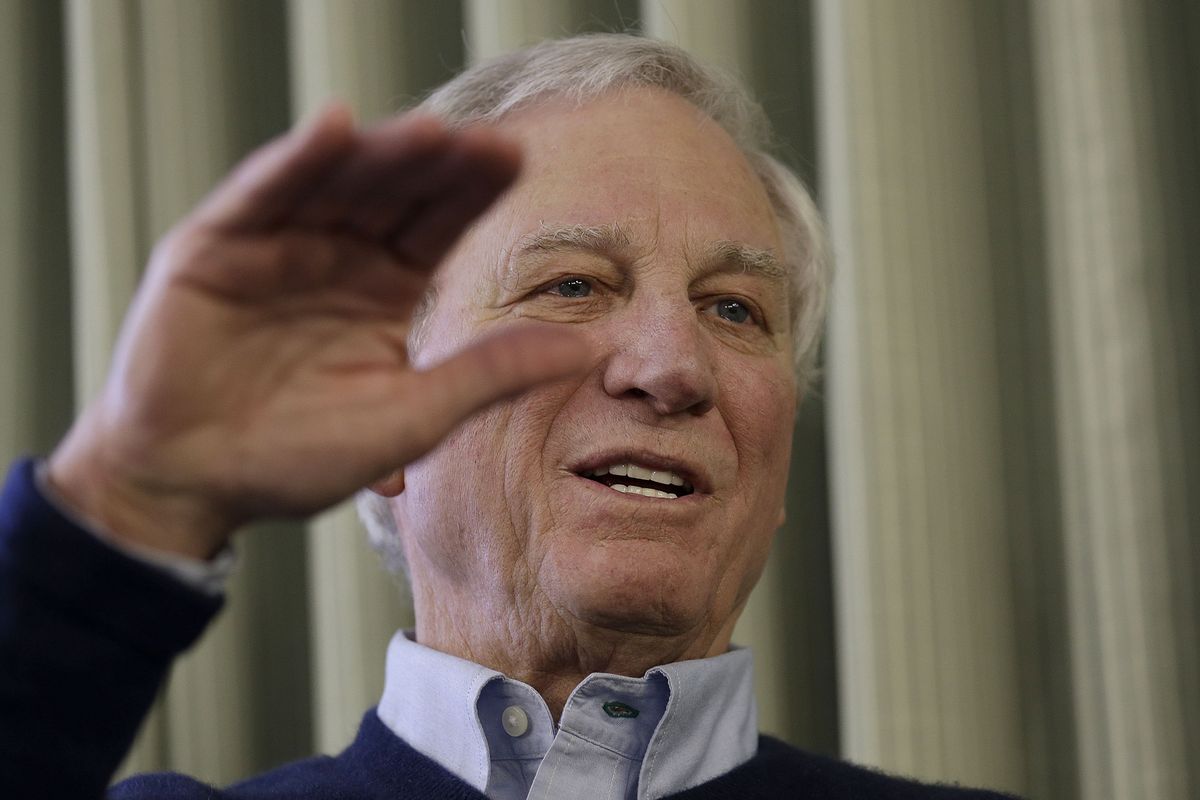

But four men remember: Norm Dyhrenfurth, 94; Jim Whittaker, 84; Tom Hornbein, 82, and Dave Dingman, 76. The leather boots that stayed wet for weeks. Oxygen canisters that weighed 15 pounds. The shrugs of indifference most of their countrymen gave a half-century ago to what it takes to get a U.S.-led mountaineering expedition to the top of Mount Everest.

“Americans, when I first raised it, they said, ‘Well, Everest, it’s been done. Why do it again?’ ” Dyhrenfurth recalled Friday as he and three other surviving members of the 1963 expedition gathered in the San Francisco Bay Area for a meeting honoring the 50th anniversary of their achievement.

The American Alpine Club this weekend is recognizing the pioneering climbers and what their feat came to represent in the years after President John F. Kennedy honored the Everest team with a Rose Garden reception. Life magazine even devoted a cover to the subject: the birth of mountaineering as a popular sport in the U.S.

Whittaker, who lives in Seattle and went on to become chief executive of Recreational Equipment Inc., was the first American to summit Everest. He and his Sherpa companion, Nawang Gombu, reached the top of the world on May 1, 1963, a decade after Great Britain’s Edmund Hillary and about six weeks after another climber on the U.S. expedition, Jake Breitenbach, died in an avalanche.

Memories of how close he came to his own death on Everest – he and Gombu ran out of oxygen on the summit and had to climb up and back without water after their bottles froze – infused every day of his life since with gratitude and child-like wonder, he said.

“I think I will probably take it with me into my next life, if I have one,” Whittaker said.

Three weeks after Whittaker’s ascent, two other Americans, Hornbein and the late Willi Unsoeld, became the first men ever to scale Everest via a more dangerous route on the mountain’s west side. The next day, they descended by the southern route that Hillary, Whittaker and, by then, two more members of the American team, had taken to the summit.

The adventure, which included spending the night without sleeping bags or tents at 28,000 feet, made them the first men ever to traverse the world’s highest peak – and cost Unsoeld nine frost-bitten toes.

Dingman has been lauded over the years for sacrificing his own chance to scale Everest to belay Hornbein, Unsoeld and two other climbers, Barry Bishop and Lute Jerstad, who had gotten stuck out in the open with them, back down to base camp.

Dingman never made it back to Everest. He said he has no regrets.

“It would have made no difference to get two more people on to the summit, but if we had lost two or three people on the way down that would have been a very different story,” he said.