Paris slayings put spotlight on Kurdish female warriors

Women play prominent role in separatist group in Turkey

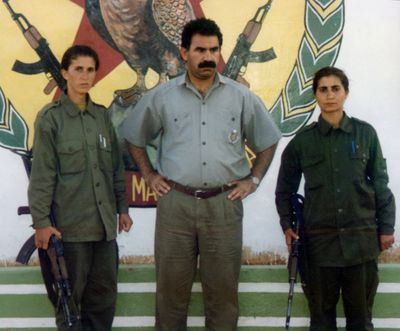

ANKARA, Turkey – The photograph shows a young woman in guerrilla fatigues, long hair tied back, toting a machine gun. She stands next to Abdullah Ocalan, the feared leader of Turkey’s separatist Kurd militants – testimony to her senior role in the insurgency.

The scene was a guerrilla training camp at the height of the Kurdish rebellion. The woman was Sakine Cansiz – the exiled Kurdish activist who was found shot dead along with two other women on Thursday in Paris.

Cansiz, who went by the nom de guerre “Sara,” was legendary among Turkey’s Kurds as a founder of the separatist movement, a champion of women’s rights and an unbreakable warrior who endured years of torture in a Turkish prison. A 2007 cable from the U.S. Embassy in Ankara, released by the secret-spilling Wikileaks website, shows that U.S. officials had identified Cansiz as one of the outlawed PKK’s top two “most notorious financiers” in Europe and wanted her captured to stop the flow of money to the rebels.

And her life and death put the spotlight on a seeming paradox: Women have played a prominent leadership and combat role in the insurgency of an ethnic group known for its conservative, male-dominated values.

The 55-year-old Cansiz was found at a Kurdish information center in Paris with multiple bullet wounds to the head. Two other Kurdish activist women lay dead beside her. French authorities called the attack an execution and hundreds of angry Kurds immediately gathered outside the building claiming the killings were a political assassination.

There was no immediate claim of responsibility. Kurdish activists blamed Turkey for the deaths while some Turkish officials pointed at a possible feud between factions within the PKK, the Kurdish acronym for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party.

The killings come at a time when Turkey has resumed talks with jailed rebel leader Ocalan in a bid to persuade the group to disarm and end the nearly 29-year-old conflict that has killed tens of thousands of people. Some speculate that the slayings may have been an attempt to derail peace efforts.

Cansiz and Ocalan’s now-estranged wife, Kesire Yildirim, were the only two women among a core group that founded the PKK in a village in southeast Turkey in 1978. The organization has since grown into one of the world’s bloodiest separatist groups, where women make up around 12 percent of the estimated 5,500 fighters.

Details about Cansiz’s early years are sketchy. Turkish and Kurdish reports say she became a Kurdish and youth activist in the mainly Kurdish province of Elazig in the 1970s before helping to found the PKK at a “congress” while in her early 20s. She was arrested during Turkey’s 1980 military coup and thrown into a prison in the city of Diyarbakir that was infamous for torture and ill-treatment.

After her release in 1991, she spent time in PKK camps first in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, which was controlled by Syria at the time, and later in northern Iraq, where she led and organized the group’s women’s wings.

At the height of the conflict between the PKK and the Turkish security forces, an estimated 20 to 25 percent of the group’s fighters were women, according to Nihat Ali Ozcan, a terrorism expert at the Ankara-based Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey.

In March, Turkish security forces killed 15 female Kurdish rebel fighters in a clash in a forested area in southeast Turkey, believed to be the largest one-day casualty toll for women guerrilla fighters. A Turkish security official, speaking on condition of anonymity in line with government rules, said security forces did not realize they were fighting women until all were killed and they recovered the bodies.

The PKK originally set out to fight for a separate state for Kurds, who make up an estimated 20 percent of the Turkish population. It later revised its goal to autonomy and greater rights for Kurds, including the annulment of Kurdish language bans imposed in the 1980s.

Cansiz received asylum from France in 1998, according to Devris Cimen, head of the Frankfurt-based Kurdish Center for Public Information.

The Wikileaks cable suggests that Cansiz and another PKK member, identified as Riza Altun, were the PKK’s key financiers in Europe, helping to funnel “upward of $50-100 million annually” to the organization. The PKK is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey and its allies, including the United States.

The cable suggests that the PKK raises money in Europe through fundraising and business activities as well as drugs, smuggling and extortion.