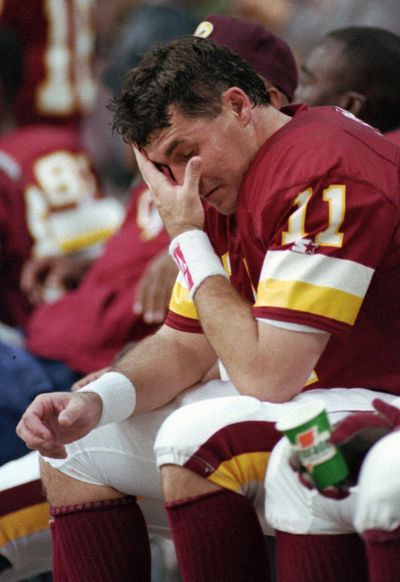

Mark Rypien witnessing worrisome outcome of athletes’ trauma

The charity golf events he hosts and plays in are a joy for Mark Rypien.

The causes are close to his heart, someone’s swing is bound to be source of high comedy and the company can’t be beat, whether he’s teeing it up with friends from his high school days at Shadle Park or former Washington Redskins teammates or, especially, NFL legends he’s long admired.

But more and more now, a shadow intrudes on the laughter.

Just last month Rypien hosted the Mickey Steele Celebrity Tournament at Queenstown Harbor in Maryland, raising money both for his own foundation and Redskins charities. More than 50 ex-players showed up, and Rypien renewed his bonds with all of them. He also came away a little shaken.

“You’re with them when they played, when they’re full and vibrant,” he said, “and to see some of them in the shape they’re in now, it’s very alarming.

“These are guys we all cherished as Redskins, and you accept that physically it’s going to be tougher for them getting around. But you’ll be talking to them and sometimes there’s a blank stare and you wonder where they are, and you know there are connections that aren’t being made. Yeah, some of these guys are in their 60s and 70s, but it’s more than that. And that really hit me this year for some reason.”

Could be that the reminders are beginning to bump together in such a way that they can’t be ignored.

He is among a growing chorus of former National Football League players suing over concussion-related injuries, claiming the league hid or even lied about risks to players and isn’t doing enough toward post-career care for brain trauma. They number more than 4,300 now, including other locally grown players like Gail Cogdill, Cory Withrow and Rollin Putzier. On July 22, U.S. District Judge Anita Brody is expected to rule on whether those suits can move forward in court rather than arbitration, where the NFL wants them handled.

Rypien’s participation was bracketed – and his reality rocked – by the suicides of contemporaries Dave Duerson and Junior Seau, both later found to have had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative condition linked to concussions.

More recently – and even closer to home for Rypien – was the suicide of his cousin. A National Hockey League grinder who had suffered from depression, Rick Rypien also played with rough-and-tumble abandon, and the pounding he took as an undersized enforcer likely exacerbated his mental health issues.

And then there are the gaps and disconnects Rypien senses, things beginning to haunt his own days.

He is 50 now, 12 years removed from his last game and 21 from his Super Bowl MVP performance against Buffalo. But already he has experienced memory problems, significantly enough that he has recorded conversations to track details of daily life. Blessed with a facility for putting names with faces, he’s finding that gift betraying him. He admits to bouts of depression.

“I don’t know if that’s normal,” he said, “or is it magnified because of what I did for a living?”

If he wasn’t a Duerson or a Seau whose job entailed inflicting hits, Rypien played football’s most vulnerable position, and he sustained “two or three” concussions with the Redskins. In particular, he cites a game against Minnesota when he was rocked after an 8-yard scramble (“a miracle in itself,” he laughed), came to the sideline to get the play from Joe Gibbs – a staple from the Redskins game plan – and promptly told the coach, “We don’t have that play.”

“Except I was thinking of our playbook at Washington State,” Rypien said, noting there were probably another dozen times “when I spent a series out there wondering, ‘Where am I?’

“Now I’m not naïve. That’s the inherent risk. You can’t put flags on us and take the helmets away. We’re gladiators and the job is to keep going out there.”

This is Rypien’s particular conflict. He’s forever wedded to football. He expresses regard for steps the NFL has recently taken in concussion-related education, diagnosis and safety. He understands, too, that many fans think the suing players are trying to erase their own personal responsibility, even as those critics ignore evidence that NFL-hired physicians and consultants not only dismissed links between concussions and CTE but actively tried to discredit such research.

“I want to fight for something for the common good,” Rypien said. “You do this for the guys who are really struggling and having a hard time. I see that and it’s frightening. How can I know what’s ahead?

“So let’s do something for all the guys who played before, and after, me, and maybe put something in place, something positive in the way of after-care or neural health – so we can move on and still enjoy this game we love.”