Large dose of reform: Washington embraces Affordable Care Act

Health care, American-style, is about to undergo the biggest change since the enactment of Medicare 48 years ago.

In quiet office buildings far from the glare of television cameras, officials worry that people who need these changes have no idea what’s coming. Health insurance is complicated, and there’s been no lack of controversy to obscure the emerging structure of reform.

But in Washington state, reform is becoming reality, more rapidly than in most areas of the country.

Over the next week, The Spokesman-Review will describe Washington’s effort to implement what many call “Obamacare” – a law of the land, enacted in 2010, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, validated during a hard-fought presidential election, and known officially as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Here’s what that federal law will do:

• Push uninsured individuals to get health insurance, and employers to provide it.

• Apply tough federal regulations to the health insurance industry, prohibiting practices that made coverage unaffordable or unavailable when people needed it the most.

• Provide insurance carriers with federally funded safeguards, so carriers would be more willing to sell their products in compliance with the tough federal rules.

• Create websites, one for each state, where uninsured individuals and small businesses can sign up for health insurance coverage for themselves or their employees. Cost will begin at zero for low-income Americans, and go up as an applicant’s income rises. On these websites, insurance companies will compete with one another. The websites will rate the quality of the competing insurance plans, using a star system like Amazon.com’s, so paying customers can compare the plans on an apples-to-apples basis.

These websites are to begin operation Oct. 1, selling insurance that will take effect Jan. 1, 2014. If a state declines to operate its own website, a federal website will serve the state.

• Fund an aggressive communication and outreach program, so people who need insurance will hear about the opportunity to get it, with in-person assistance for those who have questions or lack access to a computer.

• Subsidize the cost of health insurance with federal money. That’s why insurance will be available at no cost for many and at low cost for many more. But here lies a dispute: Some predominantly Republican states, such as Idaho, are still debating how much of the federal subsidies they will accept.

What will politicians do?

In politically liberal Washington, however, the governor and Legislature so far have embraced the federal law. Even though debate lingers in the Senate’s Republican caucus, leaders say it’s not likely the Legislature will stymie health care reform with a partisan standoff.

Federal funding, in particular the controversial money to expand Medicaid, “is a win-win for the state and the people in Washington,” said state Sen. Randi Becker, R-Eatonville, who chairs the Senate Health Care Committee. With federal dollars to expand Medicaid, low-income people will “get insurance they don’t have right now.”

Those words do not come easily from a Republican, Becker acknowledges. But when she went doorbelling in her last campaign, “It was amazing to hear the lack of trust, the lack of respect” that voters feel toward legislators in Washington, D.C. After “crisis after crisis” in the nation’s capital, Becker asks herself: “Can we do better?”

From office buildings in Olympia, filled with professionals laboring to implement the federal law, will come the reply, spoken not in words but in deeds.

“The difference between local politics and D.C. politics is, we have to live with each other here. It creates an atmosphere of cooperation,” said Richard K. Onizuka, CEO of Washington state’s Health Benefits Exchange. Onizuka sits in the driver’s seat for Washington’s implementation of the federal law. His agency will operate the website where subsidized health insurance will be sold.

The changes he oversees will be profound.

Today, it takes 45 days for the state to investigate and approve an application for Medicaid coverage.

But on the new website, approval is expected to take 15 to 30 minutes, Onizuka said.

And the speedier application process is only one small aspect of the coming changes.

“I don’t think the public realizes how big this is, whether they agree with it or not,” Becker said. She emphasizes she is “not the biggest fan” of the federal law. But she declares that “anybody who worked in the medical field, like I did, knows there had to be reform.” Becker has years of experience as a medical clinic administrator. And like many Americans, she knows personally the anxiety of watching a loved one contract a serious disease, lose health insurance and struggle to secure at least a catastrophic plan to cover the life-saving care.

The human consequences

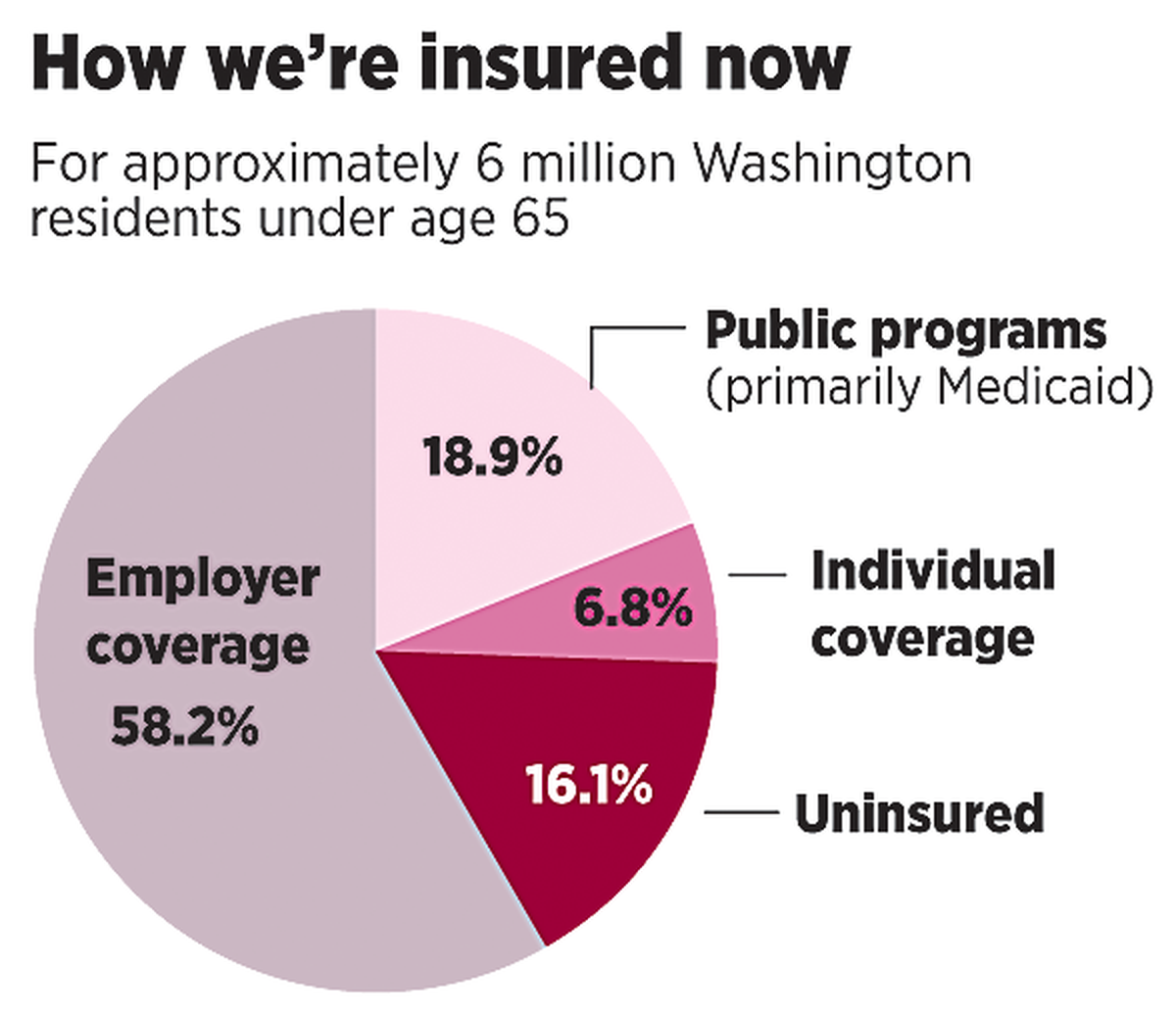

Statewide, more than 727,000 adults have no health insurance.

The Affordable Care Act was designed to solve that problem, one with wrenching human consequences, seen regularly on the pages of this newspaper:

• When people with no coverage get seriously ill, their friends organize bake sales, car washes and desperate publicity campaigns to raise money for the bills. Why? Because many types of medical care are not available in hospital emergency rooms, the one place where uninsured Americans can go for life-saving help.

• Sixty-two percent of personal bankruptcies result from medical expenses, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

• According to a 2009 study published by the American Journal of Public Health, “Lack of health insurance is associated with as many as 44,789 deaths per year in the United States.”

• For families who do have health insurance, annual premiums are $1,000 higher due to the inflated fees that hospitals charge to help pay for uncompensated emergency room care to the uninsured, according to the Washington state insurance commissioner.

Federal insurance regulations

The federal remedy is to make insurance more available for small businesses as well as individuals.

To do that, the Affordable Care Act applies federal regulations to the powerful health insurance industry for the first time. Until now, only the states regulated health insurance carriers, and some states are tougher than others. By law, the new federal rules take precedence; if a state’s more lenient rule would contradict one of the new federal rules, the federal rule prevails.

The federal rules do not take full effect until Jan. 1, 2014. Here is a sampling of what the rules will do:

• Insurers are prohibited from charging people more for their insurance because they are sick. In the past, insurers would charge prohibitive rates or deny coverage to people with chronic or serious illnesses. After Jan. 1, an applicant’s health condition cannot be considered in rate setting.

• Insurers are required to issue coverage to individuals who apply.

• Insurers cannot put annual or lifetime limits on the benefits they will pay.

• Insurers cannot cancel coverage or jack up rates at renewal time because a customer got sick.

• Insurers cannot charge women more than men.

• Insurers cannot put sick people into a high-risk pool with high rates and healthy people in another pool with lower rates. Instead, insurers operating within a state must put all of their individual and small-group customers into a single risk pool. By putting everyone into the same pool, risks and costs are spread more broadly. That could benefit small businesses, whose rates can soar if one employee suffers a costly health crisis.

• In setting rates, insurers are allowed to consider an applicant’s age. But there’s a safeguard: The rate for an older person cannot be more than three times higher than the rate for a young person.

• In setting rates, insurers are allowed to consider if the applicant is a smoker. Again, there’s a safeguard: The rate for a smoker cannot be more than 50 percent higher than for a nonsmoker.

• Insurers are required to standardize coverage plans. This will help buyers tailor coverage to their finances. It will facilitate meaningful comparisons when people go to the state websites to compare carriers and policies.

The required options are: for people under 30, an inexpensive “catastrophic” plan, featuring a high deductible but covering preventive care; a “bronze” plan, covering 60 percent of costs; a “silver” plan, covering 70 percent; a “gold” plan, covering 80 percent; and a “platinum” plan, covering 90 percent.

Some of these rules apply only to insurance plans for individuals and small employers; large-group plans may be grandfathered in. However, the law provides that grandfathered plans could lose their exemption from the new rules if they make big cuts in their benefits.

Safeguards for insurers

Mike Kreidler, Washington state’s veteran insurance commissioner, said “there’s a lot of anxiety” about these changes among health insurance carriers.

Granted, the reforms will hand insurers a huge opportunity to expand and compete: 727,000 uninsured adults in Washington will have a chance many never had before to get health insurance coverage.

Some insurers will contract with the state to cover clients of expanded Medicaid.

And some insurers will compete on the website, offering plans to insurance shoppers armed with federal subsidies. When the Washington Health Benefit Exchange asked how many carriers wanted a chance to sell on the website, 13 companies expressed a preliminary interest in selling policies to individuals, seven expressed an interest in selling to small businesses, and four expressed an interest in selling stand-alone dental insurance coverage. (Yes, the website will sell dental coverage as well.)

But even with a market expansion this large, insurers face a real fear of the unknown: how expensive it will be to insure the new customers. “Are they sicker, or are they healthier?” Kreidler asked.

The answer will not be known right away.

In addition, insurers must figure out how much they will charge for the new federally defined benefit packages, under terms of all the new federal regulations.

No one yet knows what those rate proposals will be. Waiting to scrutinize them, though, is Kreidler. His actuaries, he promises, collect a great deal of data from the insurance industry and intend to use it: “Just because they propose it doesn’t mean we agree with it. We have a lot of authority to look at the plans they’re offering,” Kreidler said.

Congress was mindful in enacting the Affordable Care Act of the unknowns insurance companies would face. The law makes three provisions to buffer the risks: Government-run reinsurance programs will protect carriers that encounter extraordinary costs. A “risk adjustment” program will funnel dollars from carriers who attract a low-cost customer pool to carriers who wind up with a high-cost customer pool. A “risk corridor” program will funnel dollars from carriers whose costs are lower than expected to carriers whose costs are higher than expected.

Big changes for states

Insurance carriers are not alone in the race to comply with the Affordable Care Act. Since the creation of Medicaid and Medicare in the 1960s, states have cooked up vast alphabet soups of programs to care for the poor and vulnerable. Washington state, more progressive than many, runs a variety of programs aimed at needs such as mental health, breast and cervical cancer, family planning and the Basic Health plan for the working poor.

Several of these programs, such as Basic Health, are expected to disappear. The state will stop spending money on them, saving millions. In their place will be a simpler concept: comprehensive coverage, from the poorest up to middle class, buttressed with an infusion of federal subsidies.

Beginning Jan. 1, Medicaid can expand. Currently it covers people whose income falls below the federal poverty level, which varies depending on family size. For basic Medicaid, the federal government pays half the cost and states pay half. But starting in January, for states that agree, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the cost to expand Medicaid eligibility to 138 percent of the poverty level. In 2020 and beyond, the federal government by law is committed to paying 90 percent of Medicaid expansion costs.

Beyond expanded Medicaid, federal aid to the currently uninsured will reach well into the middle class. Tax credits will subsidize the cost of health insurance for purchasers with incomes as high as 400 percent of the poverty level: $94,200 a year for a family of four. The size of the tax credits shrinks as income grows.

Only on the new websites can the subsidies be obtained.

Behind the scenes, state regulatory agencies have lots of questions. Washington’s agencies, as early implementers, were among the first to raise them. Once a month, they meet with a federal implementation team to hash out details. A draft version of the federal rules to govern health insurance came out Nov. 26, and after a comment period the final rules came out on Feb. 27.

With 50 states in various stages of compliance and debate, those deadlines – Oct. 1 for the websites to launch and Jan. 1 for new policies to take effect – are creating a sense of urgency.

“We’ve had a very short runway,” said Manning Pellanda of the Washington State Health Care Authority. He is assistant director for eligibility, policy and service. His job is to figure out how to add an estimated 328,000 clients to Medicaid in 2014 and 2015. “The federal government is trying to create something they’ve never done before. It’s a big challenge for everybody,” he said.

With an effort this complex, the chance for surprises is what worries Washington Gov. Jay Inslee. That Oct. 1 deadline for an operational website – secure, fast and user-friendly – makes him determined to keep Washington’s agencies moving forward. If a partisan conflict this spring blows up the rules or sandbags the funding, there won’t be much time to modify and retest the system.

Nonetheless, on a political level Inslee said he feels optimistic: “We’ve had our family squabbles for 40 years, we made a decision, and now we’re going to move forward. We’re going to have a bipartisan success here in the next several months.”

What motivates him, he says, is the desire to prevent human tragedies, personified in a Seattle boy who sat in Inslee’s office Feb. 18. The boy lost his mother after she lost her health insurance, and then her life.