Providence, CHS have split Spokane’s health care system

Ten years ago, doctors called the shots when it came to health care in Spokane.

Most owned their practices or plied their specialties in larger clinics. They freely referred patients to other doctors and hospitals, engaged in research trials and melded into a health care community where collaboration often trumped competition.

That was then.

Today, Spokane health care is dominated by two large and aggressive hospital systems. Providence Health & Services and Community Health Systems Inc. have snapped up scores of clinics and put 60 percent of the region’s doctors – about 700 – on their Spokane payrolls. This has allowed them to pin down patient referrals and profits in what amounts to a modern-day gold rush.

It’s a dramatic shift from how the system worked just a few years ago, said Keith Baldwin, chief executive of the Spokane County Medical Society. The trend mirrors what is happening across the country. One needs to look no farther than the Puget Sound region, where Providence bought Seattle’s largest hospital system, Swedish.

Hospitals say it’s about building medical networks with the noble aim of accessibility, affordability and quality. They envision a full-service, cradle-to-grave version of managed care, all within one network.

Elaine Couture, chief executive of Providence’s large Eastern Washington division, said these networks will coordinate care as never before, enhancing efficiency and effectiveness.

Consolidation is also about making money: Health care is a $2.3 billion-a-year industry in Spokane, accounting for about 13 cents of every dollar spent. It’s anybody’s guess how the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will affect that transaction. But it’s clear the hospitals are in the strongest position to collect the lion’s share of the dollars.

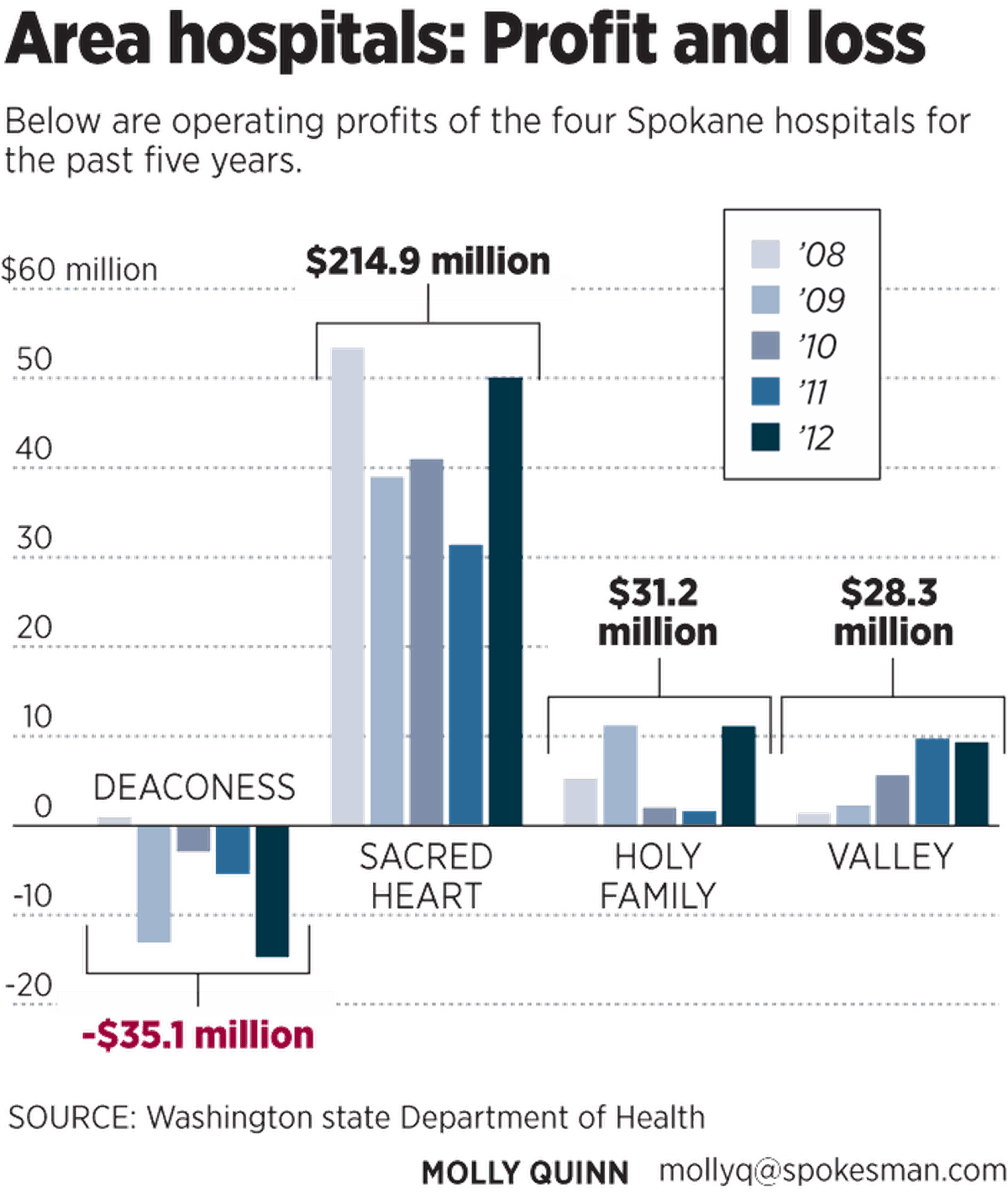

Last year, three of Spokane’s four hospitals captured combined profits of $71 million, led by Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center’s $50 million.

Deaconess Hospital, a major piece of Providence competitor CHS’ Spokane-based Rockwood Health System, recorded a $14.7 million loss as it adjusts to changes including the Providence buyout of Spokane Cardiology, which had been a lucrative partner of Deaconess for many years.

Company executives, however, say those operating losses don’t reflect the true state of Deaconess. Tim Hingtgen, CHS division vice president overseeing Spokane, said a widely accepted accounting method that stock analysts and company financial officers use lists Deaconess with a $15 million profit.

Although much of the money spent on health care locally is recycled in Spokane through construction projects, equipment purchases, and community grants and projects, dollars also are sent upstream to out-of-town corporate offices.

At Providence, for example, 20 executives based in Renton, Wash., were paid more than a million dollars apiece in 2011. Of those, four senior vice presidents collected more than $3 million a year in salary and other compensation. Providence chief executive Dr. John Koster led all of them with $6.4 million. None of those million-dollar salaries paid in 2011 went to Providence’s leaders in Spokane.

CHS, based in Tennessee, is the largest publicly traded hospital company in the United States. Its chief executive, Wayne Smith, received pay totaling about $21 million in 2011. Several other executives were paid millions, according to financial filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The salaries of local executives were not published.

Hospitals paid more for procedures than clinics

While federal health care reform began the task of determining who should pay for health care, it did little to answer the bigger question: How can costs be controlled?

Hospitals make easy targets for cost-cutters, with numerous employees, high salaries, and expansive and sometimes opulent buildings and grounds.

And studies show hospitals are paid more than doctors in private clinics for the same procedures and treatments.

It’s why each of Spokane’s cardiology practices sold to a hospital in 2011. Those sales came as Medicare, the federal government’s health insurance program for seniors, sliced reimbursements as private insurers had done. Similar alignments have happened across the country.

Here’s how it works: Hospitals are allowed to charge facility fees for outpatient care to help recoup the cost of their infrastructure. So hospitals can buy a clinic and collect more money for the same service than the freestanding clinic could, according to insurance industry trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans.

It’s among the reasons why Premera Blue Cross, the largest health insurer in Eastern Washington, fears that hospital integration will not streamline services and shave costs.

“Historically, large consolidations or mergers have led to higher health care costs for our customers as a result of dominant market share positions for some providers,” Premera executives wrote in response to an interview request. “With that said, we have been encouraged by the stated commitment and recent work of a number of the hospitals and physicians clinics with which we collaborate the most, including Providence and Rockwood/CHS.”

A PricewaterhouseCoopers report found that the alignment between doctors and hospitals has been driven by financial opportunity, access to electronic medical records, and less risk in the face of reforms that will eventually include payment schemes other than traditional fee-for-service.

Dr. Craig Whiting, chief executive of Rockwood Health System, expects that as changes wrought by health reform become clear, large hospital systems could look beyond providing medical care into offering insurance, a move that would make them akin to Group Health Cooperative. Gathering many specialties under one roof would be key to that transition. Providence already sells insurance in Oregon.

Yet Warren Benincosa, chief executive of Cancer Care Northwest in Spokane, takes a skeptical view of hospital claims that bigger is better or cheaper.

Cancer Care Northwest, Spokane Internal Medicine and Northwest Orthopaedic Specialists are the largest independent medical groups left in Spokane. With 22 physicians, the cancer clinic treats two-thirds of all the region’s cancer patients. Benincosa acknowledged that both Providence and CHS have expressed interest in buying the clinic.

“We have concerns about consolidation and control,” he said, noting that Cancer Care Northwest once was owned by U.S. Oncology, a national company. The arrangement didn’t sit well with the physicians, and a change back to local control and ownership was re-established.

“We have learned some lessons about this issue along the way,” Benincosa said.

Cancer Care’s physician group, however, knows that operating independently in a city where sides have been chosen is risky.

The large systems could decide to get into the cancer treatment business, recruit oncologists and then have their network of primary care physicians refer cancer cases.

Already, Benincosa said, referrals from one hospital group have declined. He declined to elaborate.

“We know we can’t hang out there by ourselves,” he said. “We wouldn’t mind having a tertiary partner of some kind.”

The trail to consolidation

Tracing the expansion of the two hospital systems goes back more than a decade.

In 2002, Deaconess and Valley hospitals, both owned at the time by nonprofit Empire Health Services, lost a combined $14 million. Layoffs followed.

Empire later initiated across-the-board wage cuts in hopes of instilling a shared-pain camaraderie among the staff. Instead the cuts sapped morale and some employees left. Many who remained decided to unionize.

Empire’s board of directors looked to interim executives who specialized in turnarounds. Despite a few promising stretches, it became clear that Deaconess would either align with another hospital system, close or be sold.

At the same time, the local Providence hospitals – Sacred Heart, Holy Family and those in Colville and Chewelah – expanded services, opened a children’s hospital and formally merged in 2006 with the larger Providence system based in Renton.

Empire’s urgency grew, and in 2008 its board reached a blockbuster deal: Empire sold its Deaconess and Valley hospitals to CHS, a for-profit hospital chain with a record of financial success.

CHS moved quickly in its efforts to rehab Deaconess and Valley. The company spent $114 million in four years on new equipment and building projects.

All the while, the physician owners of the region’s largest multispecialty clinic, Rockwood, were itching for change, said Whiting, the chief executive.

With dozens of doctors and a sterling reputation, Rockwood’s ambition grew during a 2006 strategic planning retreat.

“We began to recognize that we wanted, needed, to be financially and strategically aligned with a hospital system to be nationally recognized as a center of excellence,” Whiting said.

Plans began to jell in the first half of 2008 as it became evident that either Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton would win the Democratic presidential nomination and had a good chance at the Oval Office. And with that leadership change would come health care reform.

In early 2009 Rockwood went courting.

While Providence acted aloof, CHS drew up a battle plan: Pay $50 million for Rockwood and use the big clinic and its thousands of patients as a catalyst to build an integrated health system that included the hospitals. Deaconess was already among the largest hospitals in the CHS system, and now Spokane would house its first integrated health network.

The buyout was a thunderbolt.

Dr. Andrew Agwunobi, Providence’s local leader at the time, reacted angrily. Rockwood had been the largest patient referral center for Providence hospitals, and now those patients would be directed to Deaconess and Valley.

The first Providence counterpunch was essentially to evict Rockwood’s physicians from the Providence campus in 2010. A back-and-forth ensued: CHS successfully fought back a Providence expansion plan for Sacred Heart, accusing the large hospital of predatory behavior. A Sacred Heart expansion would cripple CHS’ efforts to rehabilitate Deaconess, according to legal filings made with regulators at the Washington State Department of Health.

The Rockwood acquisition set off a domino effect of clinic moves and buyouts. Worried about patient admissions, Providence began buying independent practices and aligning with others. It entered into a close partnership with Seattle-based Group Health to ensure the cooperative’s 90 doctors in Spokane refer their patients to Providence’s specialists and hospitals.

Agwunobi was turned out as CEO of Providence’s local division in mid-2011 and within months left the organization altogether.

Providence turned to former Sacred Heart President Mike Wilson to make use of his decades of dealings with doctors and business leaders. He hired Dr. Kevin Sweeny, a former chief executive of Rockwood, to lead Providence’s physician recruitment.

Wilson is now retired but remains tied to Providence as a consultant.

Lately, Valley Hospital has found a money-making recipe that includes community outreach and a growing joint-replacement business, a historically profitable medical service. In each of the past two years Valley has earned profits nearing $10 million.

The money and potential of the fast-growing Valley area have attracted Providence. Today, construction crews are busy building its $60 million medical campus just east of Sullivan Road along Interstate 90.

Good care for all patients

Couture, who now runs Providence, said the hospital system has emerged from the changes with a clear focus on mission and the financial margins to pay for it.

Providence, she said, plans to welcome as many new patients as it can handle as health reforms taking effect next year provide 70,000 uninsured Spokane residents with medical coverage. Providence has 456 doctors and advanced care practitioners in its system. While they tend to the sick, others will embark on initiatives that focus on disease, wellness, housing and other denominators that affect the health of everyone – rich, middle class, poor and vulnerable, Couture said.

Bill Gilbert, the chief executive in charge of day-to-day operation at Deaconess, said he believes the hospital’s struggles should ease as the economy rebounds, health care reform settles and consolidation expenses diminish.

“Everything we do … is with an eye on the long term,” he said.

Added Hingtgen, the CHS vice president, “We feel pretty confident in the local marketplace. We’ve learned some lessons.”

As the dust settles, Rockwood’s Whiting said the consolidations will work.

“Is bigger better? I think unequivocally it is,” he said. The Rockwood system has recruited more than 70 physicians to Spokane.

“Have we lost something in return? Yes,” Whiting said, recalling the days of small physician practices and collaboration.

Still, he said, “When we had a more fragmented system, we often had good care being delivered. But it wasn’t that way for all patients. That’s what we hope will change.”