Wyoming hunter discusses bear attack

Twenty-one years after he was attacked by a grizzly bear sow while hunting bighorn sheep in northwestern Wyoming, Terry Everard still recalls the incident clearly and still carries the now-hidden scars as reminders.

“When it happens to you, all you wish is that it will stop,” he said in a telephone interview.

Now 58 and retired in Sundance, Wyo., Everard still hunts and still has a great respect for grizzly bears and their power. He preaches safety in the backcountry, including suggesting that hunters and hikers carry bear spray and have it ready for use.

“I have no animosity against bears,” he said. “I still bowhunt today, I’m just very careful.”

Everard grew up in Cody, Wyo., and was hunting with two friends in the Sunlight Basin when he startled a sow grizzly with cubs that had been snoozing after raiding squirrel middens to feed on whitebark pine seeds.

The sow was only about 40 yards away when it stood up on its hind legs from behind a log, saw Everard and charged. Because he was attempting to fill his bighorn ram tag, he was carrying a .270 rifle, but he didn’t have a bullet in the chamber and doubts if he would have had time to shoot anyway, since the sow closed the distance between them so quickly.

All he had time to do was drop to a squatting position with his head down and cover his neck with his hands. With a backpack on, the bear concentrated its attack at his upper body. Down feathers from his torn coat flew into the air as the bear clawed his arm.

“It just goes on and on, it just seemed like an eternity,” he said. “And you just feel helpless.”

The bear gave him a black eye from pushing down on his head so hard.

In an attempt to end the attack, Everard reached for his rifle with his left hand, loaded a round and fired into the air. The bear stopped its attack and backed away, blood smeared on its fur. Loading another round, Everard prepared to shoot if the bear charged again. It turned and ran.

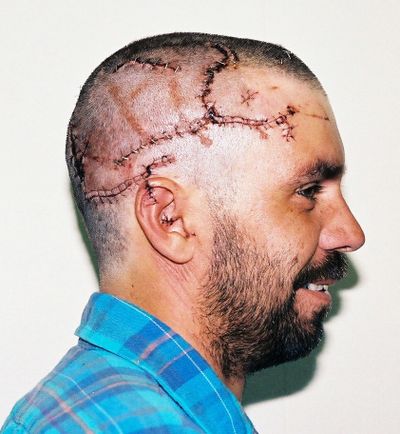

The bear had bitten at his head, shoulder and arm in the 40-second attack, causing injuries that would require more than three and a half hours of surgery and 250 stitches to close up. Because of the long time it took him to first walk, then ride a horse and finally travel in a pickup truck to the Cody hospital, Everard lost an estimated four units of blood.

“If I had lost another pint, I would’ve been in trouble,” he said.

Although the attack was traumatic, Everard said, it hasn’t affected him much.

“Everything that happened to me was superficial,” he said.

Most of the blood loss came from lacerations to his scalp, which bled profusely. The injury to his shoulder was bad enough to keep him from bowhunting that fall, but no bones were broken.

“The worst thing that happened to me was I couldn’t bowhunt that year,” he said. “I love to bowhunt. I still bowhunt today.”

Sure, he’s had a few bad dreams about bears. But he wasted no time returning to the site of the attack to try to make sense of what happened and to retrieve his backpack, which he had discarded as he fled quickly downhill to the hunting camp.

Although tracks of a grizzly with cubs were found in the area, there was no blood near the tracks, convincing Everard that the blood he saw on the bear was his own.

And he returned to the region to fill his bighorn sheep tag, eventually bagging a three-quarter curl ram on the second-to-last day of the season.

It was Everard’s father, Billings resident Jim Everard, who suggested his son speak at his Assembly of God church.

“He tells a good story,” Jim Everard said.

It’s a cautionary tale that anyone who ventures into grizzly bear territory should heed.

“People just have to be more prepared,” Terry Everard said. “Don’t hunt alone. Carry pepper spray, and not in your backpack.”