Longest-held Idaho prisoner resurrects case from riot

BOISE – Ronald Lee Macik is inmate 12680, the lowest number among 8,700 felons in Idaho prisons. It’s a lonely distinction: Nobody else locked up in 1969 when guards first escorted a 21-year-old Macik through the State Penitentiary’s sally port remains behind bars.

Now 65, he’s still trying to get out. And last week, the Idaho Court of Appeals, at least temporarily, breathed new life into Macik’s bid to undo his guilty plea in the murder of another inmate during a 1971 prison riot.

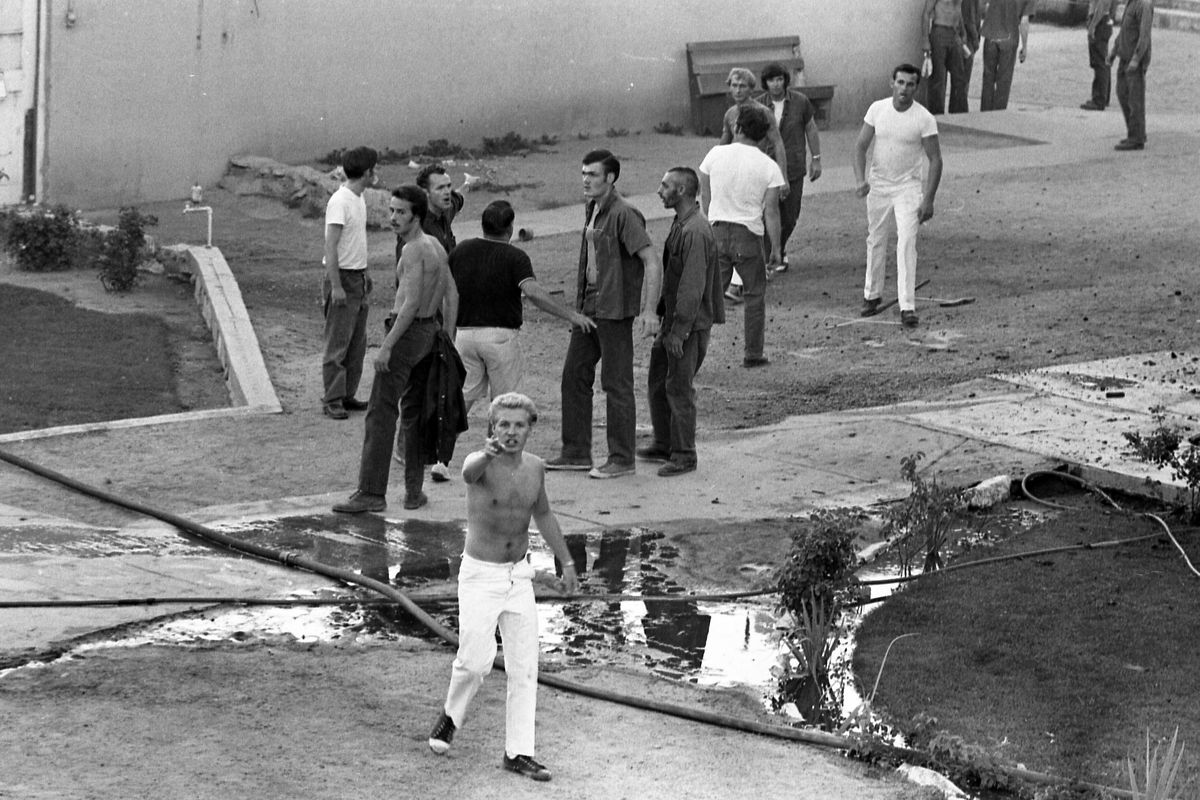

Regardless of whether Macik’s long-shot appeal succeeds, it dredges up a dark piece of Idaho prison history.

The 1971 riot – and Macik’s role in inmate William Henry Butler’s slaying – was a turning point in galvanizing public opinion behind shuttering the Idaho Territory-era penitentiary in east Boise. The bloody melee also changed attitudes about running a modern prison system and motivated officials to speed work on a new prison complex in the desert south of Boise.

The 101-year-old “Old Pen” closed in 1973, after another riot, and has since become a popular tourist site.

“In the professionalism of corrections in Idaho, certainly in the 1971 riot, you see an example of a turning point,” Amber Beierle, the historian who manages the site, said last week. “Internally, it led to many investigations.”

Beyond its claustrophobic quarters, poor ventilation and tiny solitary confinement cells known as “Siberia,” the penitentiary offered no opportunity to segregate the most-dangerous prisoners, officials complained to the Associated Press after the riot. When laundry facilities broke down, prisoners were deprived of clean clothing. Meanwhile, guards manning the catwalks and poorly situated towers atop the sandstone exterior walls received scant training, Beierle said.

“It was literally, ‘Here’s your uniform and a gun. Go out and guard,’ ” Beierle said, adding escapes became so common in its final years, residents of homes nearby joked about erecting “Prisoner Crossing” signs on their streets.

Macik, a Pennsylvania native originally sentenced in 1969 for robbing a Kellogg bar, concedes he played a role in the three-hour riot on Aug. 10, 1971. The mayhem began during a late-summer heat wave where cellblock temperatures hit 118 degrees. It began, Macik contends, after he stabbed another inmate, Charles Rice, with a makeshift knife.

In the ensuing chaos, inmates burned the prison hospital and social services building. Butler’s stabbed and beaten body was found Aug. 14, 1971, rolled up in a gym mat.

But while Macik acknowledges bringing Butler, a convicted rapist and murderer, to the gymnasium where he was ambushed, he says he didn’t kill him.

“I didn’t murder this guy,” Macik said in an interview from the Idaho Correctional Center near Boise.

Four decades after the statutory deadline for his appeal passed in 1973, Macik says he’s owed a fresh trial on these grounds: Back in 1971, he was heavily sedated, preventing him from sticking up for himself. He also says it took decades for him to learn that another inmate, Danny Ray Powers, had confessed to Butler’s slaying; had he known in 1971, Macik said, he never would have pleaded guilty.

And then there’s this: Macik says his plea was pried from him by current U.S. Sen. Jim Risch, then a young Ada County prosecutor, who visited him in jail and gave him a choice: Plead guilty, or face possible execution. “I was overwhelmed by their sheer authority over me and my inability to articulate my situation,” Macik said.

Today, Risch remembers Macik from the 1971 hearings at the old Ada County Courthouse.

“Ron Macik was probably one of the worst guys I ever prosecuted,” the Republican lawmaker said last week. “He was a bad, bad person.”

But the suggestion he climbed the Depression-era courthouse’s steps to its top-floor jail cells to pressure Macik into a guilty plea is pure fiction, the Republican lawmaker said.

“I did not visit inmates in the Ada County Jail, for obvious reasons,” Risch said. “I would have been disbarred for contacting a client represented by an attorney. I remember that I did not do that.”

The two others linked to Butler’s slaying, Powers and another inmate named William Burt, were paroled in the 1980s.

In fact, the Idaho Department of Correction has sought repeatedly to give Macik his freedom, too: Four times since 1993, he’s has been paroled – despite numerous problems behind bars, including a 1975 escape where Macik was recaptured after robbing a Pennsylvania supermarket.

Each time, however, Macik was locked up again within months for violations including drinking alcohol, possessing stolen goods and skipping town without permission, according to Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole records.

On Oct. 24, the Court of Appeals ruled that 4th District Judge Cheri Copsey in Boise had dismissed Macik’s appeal without giving him enough time to make his arguments. It gives Macik another chance to explain to Copsey his side of the story.

The Ada County deputy prosecutor leading the case against Macik’s appeal, Shawna Dunn, says the appeals court ruling was “purely procedural.”

Once that’s remedied, Dunn said, there’s nothing stopping Copsey from again dismissing Macik’s case on identical grounds: His window to appeal closed when Richard Nixon was in the White House.

For his part, Macik says decades behind bars have taught him not to be too optimistic about winning – and handing off the crown of the Idaho prisoner with the lowest inmate number to somebody else.

“I expect everything to be negative,” Macik said. “But I want a new fair trial – I never had a trial.”