Dangerous waters

South Pacific minesweeper missions still bring harrowing memories

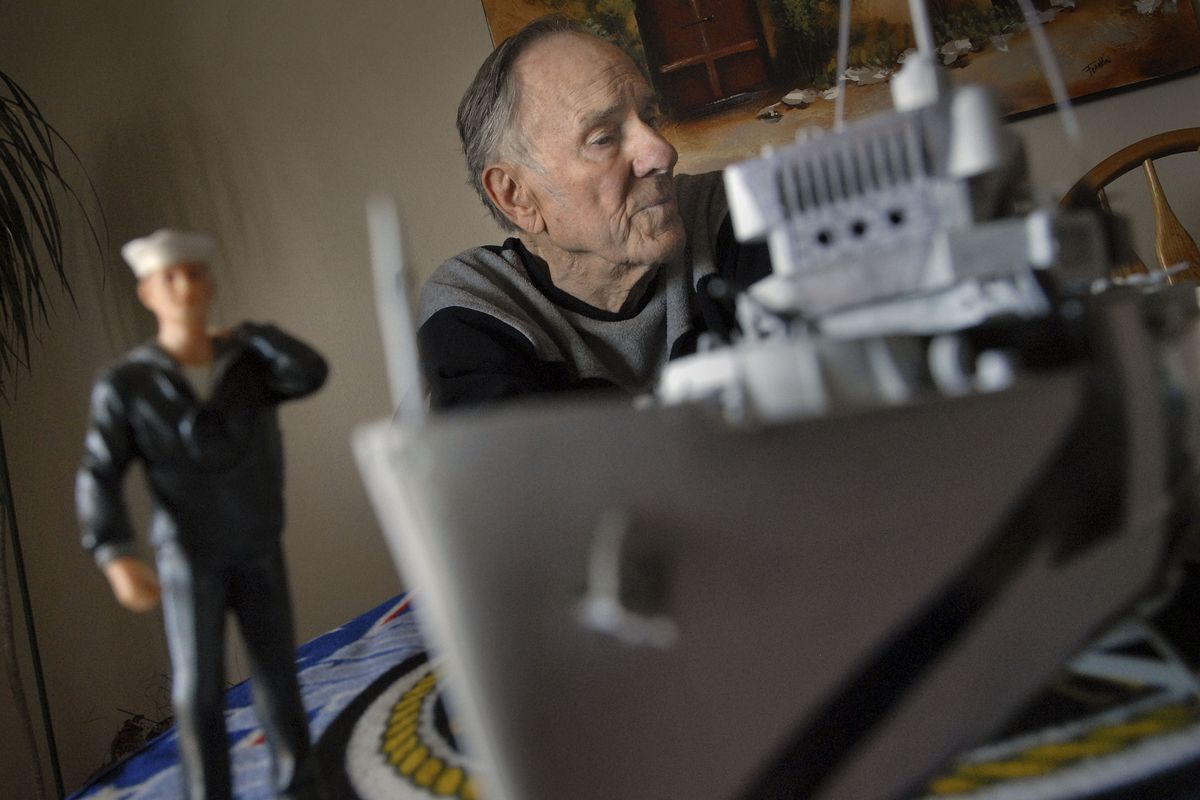

It had been more than a half-century, but Kirby Billington remembered the sound of his ship, the USS Saunter, scraping over the top of a mine in Manila Bay.

Finding mines was the Saunter’s mission. But not this way.

“We usually floated over them, barely,” Billington said. This time, “It sounded like scraping against barbed wire.”

And then, very quickly, it sounded louder. The mine blast tore a hole in the side of the ship and ended its service. Billington wasn’t hurt, but two died and 19 were injured. The February 1945 blast brought Billington’s time in the South Pacific to an end.

Five years ago, Billington prepared to board a minesweeper for the first time in decades. With his wife, Gwen, and their three adult children, the family was heading to a museum in Omaha for a private tour of a minesweeper just like the Saunter, which was eventually salvaged.

Billington’s two-year hitch on the Saunter included enough nerve-wracking duty for anyone. First there was the possibility of a mine blast hanging over every mission. There was enemy fire from shore. There was the danger of air attack and, particularly, of Japanese kamikaze planes, which dove at the minesweepers and sank some of the most noteworthy ships in the fleet. And who knew when a submarine might fire a torpedo?

For a teenager from rural Colorado, it made every dot in the sky, every flash in the ocean menacing.

“Everybody was tiptoeing around,” he said. “You get used to it after a while. Except for the suicide planes. You never get over that. A loud noise’ll still shake a guy up.

“Anytime you saw an airplane or heard an airplane or saw anything, you wondered.”

Even porpoises at night could spook a young sailor.

“Oh, God, they’d scare you to death,” Billington said. “They looked just like a torpedo coming through the water.”

The perils of minesweeping are not among the best-known tales from the well-documented war. A brief history of the Saunter that Billington keeps in a scrapbook reads: “Minesweeping is a dirty, dangerous, forgotten duty. Of their very essence minesweepers are expendable, for they are created to see that other ships might not ‘die.’ ”

The Saunter was part of a fleet important to re-establishing a U.S. presence in the Philippines after being driven out by Japanese forces in 1942 in crucial outposts of Corregidor and Bataan, among others. Billington and his shipmates were part of an intense and bloody U.S. effort to recapture those positions – and the Saunter cleared the way for six U.S. invasions.

Billington and the ship’s crew disabled 118 mines, shot down two kamikaze planes and silenced two shore batteries, according to a Navy history of the ship. Gen. Douglas MacArthur – whose headquarters were located in the Philippines before the Japanese invasion – referred to the minesweepers’ work in the South Pacific as “skillful and daring.”

Billington enlisted in the Navy as a high school senior in Julesburg, Colo. All his friends were enlisting; it was a patriotic time and it seemed like the right thing to do, he said.

After starting at the Farragut Naval Training Station on Lake Pend Oreille, he shipped out on the Saunter from San Francisco shortly after the ship was completed in April 1944. His two years in the Navy would coincide with the short, intense life of the ship.

“I got on the ship when it was built and got off when they salvaged it,” he said.

The Saunter was part of a fleet dispatched to the South Pacific to clear harbors in advance of U.S. invasions. Billington was a petty officer third-class, who performed administrative tasks and served as a “trainer” on the “three-inch-fifty” gun at the front of the ship. The trainer was one of two men who helped aim the gun at aircraft.

Life on the ship was crowded and dirty. Men slept in bunks stacked six high, and the floor in their quarters was frequently wet. They got a weekly shower – soaping up with salt water and rinsing with not quite enough fresh water to remove the “salty, icky” feeling from their skin, Billington said.

In October 1944, the Saunter and its fleet began an intense three-month period of clearing eight harbors for U.S. invasions.

The ships worked together, each dragging cables that would catch on the cables used to keep mines in place; when they ran across a mine, they’d cut it free and, when it rose to the surface, detonate it with the big ship’s guns.

After sweeping the harbors, the Saunter, along with the destroyers, would provide anti-aircraft and anti-submarine protection for the invasions. In her final mission, the Saunter swept the harbors in the Corregidor and Bataan areas while under continuous fire from shore, according to Navy accounts of the battles.

The U.S. eventually retook both Bataan and Corregidor. After all that peril, the Saunter struck a mine two weeks after the invasion, when it had returned to do cleanup sweeps in the harbor.

It was eventually towed back to California and salvaged.

While Billington was there on leave, he married Gwen, his high school sweetheart. He finished his tour of duty at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois.

After his discharge in 1945, Billington and his wife lived in Colorado for several years, and then moved to Othello, Wash., where they ran an auto-body repair business and raised three children.

After retiring, they moved to Kennewick and then into a Spokane retirement community.

For most of their lives together, Billington kept a lot of information about his time in the service – bombings, strafings, kamikaze attacks, gunbattles – to himself. Gwen Billington said she didn’t know most of the details “until about 50 years later. They just didn’t talk about these things.”