Providence facilities, doctors excluded by two large insurers in Washington exchange

Competition to control the cost of new individual health policies has led two of Washington’s biggest insurance companies to exclude Eastern Washington’s largest hospital, and many of its physicians, from their networks of preferred providers.

Hit by the exclusions are Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, Providence Holy Family Hospital and about 500 Spokane-area physicians that Providence has added to its network over the past few years.

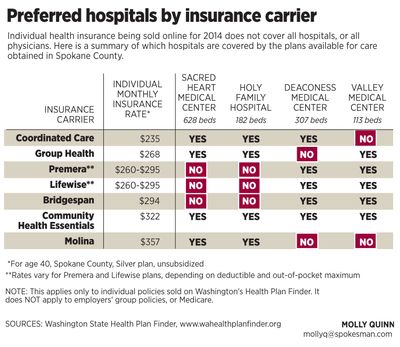

Some of the new insurance policies do cover Providence providers, but not all.

The only policies affected by these exclusions are some of the individual plans on the state’s new online marketplace, Washington Health Plan Finder. Completely unaffected are the plans by which most Americans get health coverage – Medicare for the elderly and disabled, large-group plans offered by large employers, and Medicaid for low-income people.

Still, individual health insurance occupies the national spotlight. That’s because only 58 percent of Americans under 65 have access to coverage through their jobs. To address that, the federal Affordable Care Act created online marketplaces where health insurance companies compete to sell individual policies.

But when insurance companies created policies to sell in this new market, some focused on a low price. To control price, they limited the number of doctors and hospitals they will cover.

The individual insurance plans that exclude Providence hospitals from their Spokane County provider networks are sold by Premera and its sister company Lifewise, and by Bridgespan, owned by Regence Blue Shield.

And it’s not just the hospitals. Premera/Lifewise and Bridgespan both say Providence physicians in Spokane County – about 500 doctors and practitioners from 50 clinics – are out of network for their individual insurance plans.

Premera has been the largest health insurer in Eastern Washington. Its Lifewise product is the only individual plan offered by the Health Plan Finder in all 39 counties of Washington.

Premera, Regence and Group Health are the top three health insurance companies in the state, in terms of market share and premiums written.

The individual insurance plans that do include Providence in their networks are Group Health, Coordinated Care, Community Health Essentials and Molina. None of those plans is available in all counties of Eastern Washington.

This means that for some Eastern Washington residents who go to Spokane for care, Premera/Lifewise could be the only option – blocking their access to Spokane’s Providence network unless the service they need is deemed unavailable from Deaconess and Valley hospitals and their Rockwood provider network, which the Premera/Lifewise plans list as preferred.

Why were these network decisions made?

At Premera and Bridgespan, officials explained the decision to exclude Providence this way:

Eric Earling, director of corporate communications for Premera Blue Cross, said Premera and Lifewise had conversations with providers “across the board … across the state” in the effort to build a network featuring “access to high-quality care at an affordable price.” By selecting Rockwood’s providers and the Deaconess and Valley hospitals for service within Spokane County, “we were able to offer a better price.”

Earling emphasized that if a particular medical service is not available inside this Premera/Lifewise network, his company’s customers can get coverage for non-network providers such as Providence. But, he added, “prior authorization is required.” For example, “If you’re going in for heart surgery, you’ll want to be calling in anyway, asking, ‘What should I expect?’ ”

“We encourage consumers to give us a call if they’ve got a question,” Earling said.

Rachelle Cunningham, spokesman for Bridgespan, said her company felt the Deaconess-Valley-Rockwood network is “more than adequate” to provide “the vast majority of services people would need, at a more affordable price.”

“In those instances when service is not available in the network, there would be some sort of case management that would find a way” so patients could receive what they need, she said. “I don’t think people should be concerned they won’t have access to some service that they need,” she added.

Referring to the variety of plans and networks available on the Health Plan Finder, she said: “One of the good things about this is that people have many more choices than they had before.”

Group Health, a health maintenance organization, has had a close relationship with Providence for 30 years. Kelly Stanford, Group Health’s vice president of market development for Eastern Washington, said that, unlike the other insurance carriers, Group Health did not change its provider network for the new individual policies being sold on the Health Plan Finder.

“We have been prepared for this. We have worked hard for years to be affordable,” she said, citing managed-care initiatives with Sacred Heart that reduce the rate at which discharged patients need readmission to the hospital. “If you provide good quality that’s going to keep the cost down,” she said.

Officials at Providence, meanwhile, emphasized the quality of their services. Scott O’Brien, chief strategy officer for Eastern Washington, said that in Providence’s negotiations with the health insurance carriers, “we wanted to make sure folks on the exchange (Health Plan Finder) had access to Providence. We did come to agreement with four of the providers.”

“We believe patients are going to make decisions on quality, affordability and access. At Providence, we are focused on value. That includes both quality and cost. Patients are going to need to assess the value they are getting. Not just the cost of the premium. Also the quality of the system. We are very confident that when people look at the value equation, Providence is second to none.”

Calls seeking comment from representatives of the Deaconess-Rockwood network were not returned.

Unfortunately for consumers, it isn’t easy to determine which hospitals or physicians a particular policy will cover. Provider lists are buried deep in website navigation systems, or in lengthy, hard-to-find insurance policy documentation. Providers and insurance companies offer toll-free phone numbers where the information can be obtained – if consumers are willing to wait while operators dig it out.

If consumers choose the wrong plan, the stakes are serious: They could discover – too late – that they must fight with their insurance company to access a specialist or hospital they feel they need. In general, health policies will cover providers outside their network only if the needed type of care is not available inside the network. But, if patients experience a medical emergency and arrive at an out-of-network hospital by ambulance, health insurers generally may cover the care.

Providence Sacred Heart occupies a critical space in the region’s health care services. In addition to being the state’s largest hospital at 628 beds, it provides certain services that may not be available at other hospitals in the eastern part of the state: According to Providence officials, these include heart and other advanced organ transplants; a children’s hospital; inpatient psychiatric care; and level 2 trauma center services.

Jean Gulden, a Spokane Valley insurance broker who specializes in health insurance, urges consumers to determine ahead of time whether their insurance carrier will agree to cover an out-of-network hospital or specialist. Get it in writing, she said. Then there will be ammunition if a dispute develops and the consumer needs assistance from the state insurance commissioner, who serves as watchdog over the industry.

Consumers who focus on a policy’s low price should look deeper, Gulden said. Recently she had a client who racked up a $440,000 bill at an out-of-town hospital. When such a bill comes from a provider who’s out of an insurance policy’s network, depending on the policy the consumer might face an unlimited 50 percent co-pay obligation – or more. Many health plans offer out-of-pocket maximums to limit consumers’ financial exposure; but these maximums don’t apply to out-of-network care.