This prof earned tenure in NFL

Tireless Clayton has respect of fans and league insiders

One of his ESPN colleagues tells what it’s like to go into a restaurant with John Clayton, media rock star.

They hadn’t even gotten to their table when a gentleman approached and apologized for the interruption. He asked if Clayton wouldn’t mind being introduced to his friend, who was a great admirer.

The bashful fan turned out to be former heavyweight champ Evander Holyfield.

Reminded of the episode, Clayton squinted and nodded sheepishly. “Yeah, really weird, huh?”

Weird, perhaps, but not unusual these days.

Clayton has gone from Seahawks beat writer for the Tacoma News Tribune to one of the most recognizable members of the sporting media. As an NFL expert for ESPN, Clayton’s insights are launched from countless nationwide platforms on nearly a 24-hour-a-day basis.

Hailed for the encyclopedic knowledge and scholarly demeanor that earned the nickname “The Professor,” the 59-year-old Clayton is approaching a million Twitter followers.

For context, that’s more than Seahawks coach Pete Carroll, or stars Russell Wilson, Marshawn Lynch and Richard Sherman combined.

A YouTube copy of his “This is SportsCenter” commercial of last fall has been viewed more than 3.3 million times.

And when answering questions about fantasy football during the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama reportedly said that he never sets his weekly fantasy lineup until he hears John Clayton’s injury update.

The spot-on quality of Clayton’s inside information – the result of tireless source contacts and data collection – is the key to his appeal. But the delivery plays a role, too, particularly on television.

“I think it’s fair to say that he comes across as ‘Everyman’ on TV,” said Chuck Salituro, senior news editor for ESPN TV. “He’s so well-spoken, and so (contrasting) to the look of the slick-haired Ron Burgundy-type. And I think that adds to his credibility. That, and the fact he has made a lifetime of covering the NFL, and covering it so well.”

Asked about his experience in dealing with Clayton, six-time NFL executive of the year Bill Polian offered perhaps the ultimate compliment: “Having a discussion with him is like having a discussion with another general manager. It’s as though you’re talking with a peer.”

• • •

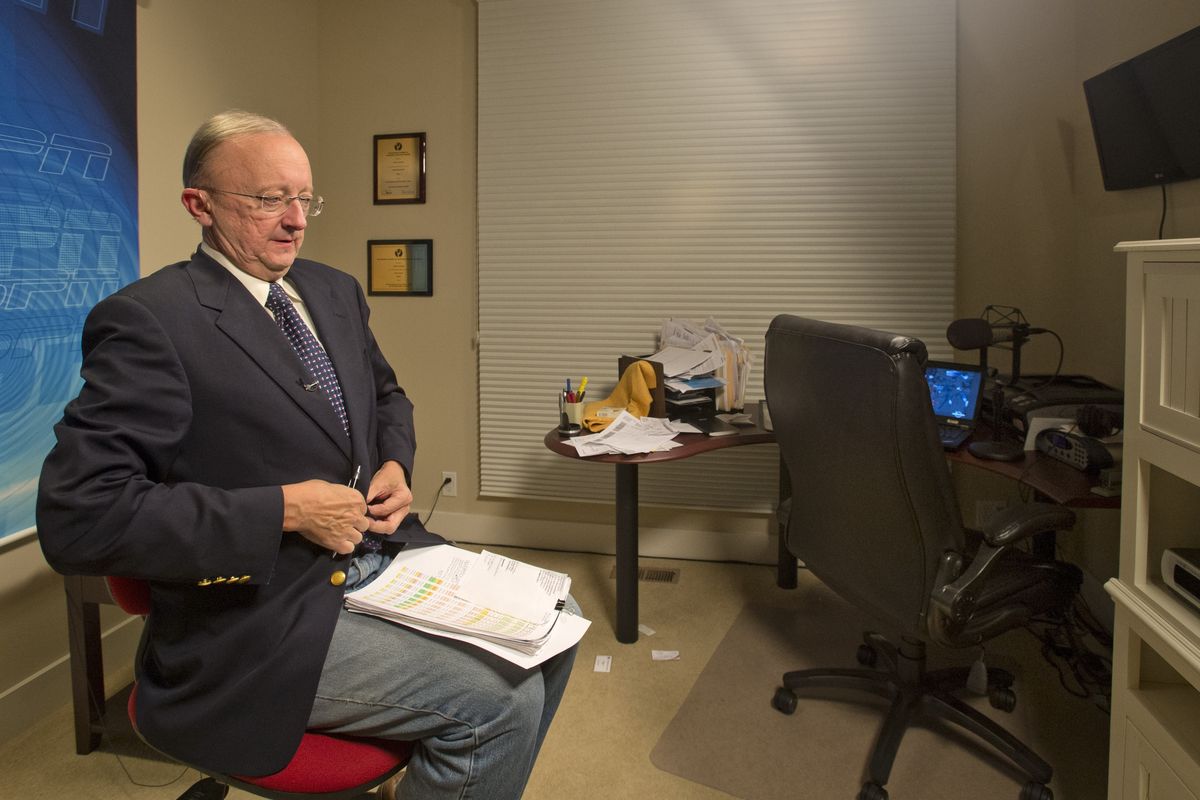

In his Renton, Wash., home, which includes a small studio with an ESPN backdrop and high-definition broadcast equipment, Clayton outlined a typical day: Up at 3 or 4 in the morning and working by 5:30 seven days a week, he puts in 12 hours a day on the job – “minimum.”

On the afternoon of this interview he already had finished radio spots with San Diego and Seattle, with more scheduled with stations in Chicago, Pittsburgh and St. Louis. Two more ESPN radio spots were on the docket, along with two TV segments – as well as being on-call to appear in the case of breaking news.

In-between, he’s on the phone with sources or updating his famed database. Several times during the interview, he paused to offer for examination the various spreadsheets that list roster and contract information for every player in the league, and salary cap figures for all 32 teams.

His own annual “statistics” tell of a life devoted to his work. Hotel nights a year: 90. Miles flown every year: 130,000. Days off? Well, he’s not sure on that one. Ten, maybe 12.

“That’s on a seven-day-a-week schedule,” he said.

Some think that 355-day annual estimate is a little conservative.

“Basically, he’s 365 days a year,” Salituro said. “We tell him to take some time off, but he won’t. He never says ‘no’ (to an assignment). If we asked him to do 10 live shots a day, he would do 10 live shots.”

The database is an insatiable houseguest that must be fed on a daily basis. He is asked if the constant updates and evaluation are crucial in case some radio caller asks, say, about the status of a Titans’ backup tackle.

“You mean Mike Otto?” he fires back off the top of his head. “He was inactive last week.”

The one question for which he had no answer was this: John, when was the last time you were stumped for a bit of information? “Hmm, I don’t know.”

• • •

Football was a cradle language for Clayton. When he was merely 6, his mother, a divorced nurse raising her only child, regularly took Clayton to Pittsburgh Steelers games.

“She’d take me to games when I was little and people were always asking. ‘Why are you bringing that bratty little kid? He’ll just sit there and spend the day eating.’ But I watched the games.”

Clayton often cites the impact of her influence, particularly her encouragement to write, which he started on his junior-high paper. Before he was out of high school, at age 17, he was stringing Steelers games for outlying papers.

At Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, he didn’t just study journalism, he lived it.

“I had 25 jobs when I was going through college,” he said. “Stringing for different papers, AP radio, CBS radio, local papers, covering high school games, covering pro games for networks, filing updates.”

When he joined the Pittsburgh Press after college, it was not as a cautious cub reporter.

Pete Wevurski, later sports editor at the News Tribune and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, worked with Clayton in Pittsburgh.

“You’d walk into the office, and there he’d be, one phone up to his ear, another phone on the other ear, and a third one extending from somebody else’s desk nearby,” Wevurski said. “He was like that most of the time.”

By the time he was 25, Clayton already created big news. Filling in for the regular Steelers beat reporter at a spring minicamp, Clayton discovered that the Steelers had practiced in pads, against the rules for that time of the year.

“I called the league office and asked if they could read me the rule,” Clayton said.

Once he verified it was an infraction, he wrote the story, and in the aftermath, the league docked the Steelers a third-round draft choice.

Coach Chuck Noll accused Clayton of espionage, and Steelers fans were not nearly as incensed with Noll for knowingly breaking the rules as they were with Clayton for reporting it.

“It was news and it was a valid story,” Wevurski said. “He took a beating for it, but his job was to report the news.”

Clayton was banned from the team’s facility until one day Steelers owner Art Rooney approached. “He said, ‘Heard they were rough on you … well, you done good, kid.’ And the ban was lifted,” Clayton said.

• • •

In a mid-’80s push to compete with the Seattle metros, the News Tribune lured Clayton with a nice raise, guaranteed travel and the freedom to cover the Seahawks as he chose – including all the electronic-media appearances he cared to accommodate.

“It was competition … I loved it,” he said. “One of the things I was insistent about was I wanted to cover the Seahawks, but I wanted to cover the whole league, too, and they were great about that.”

Gary Wright had been director of communications since the Seahawks’ inception. When Clayton arrived, Wright suddenly began seeing news in the TNT that was even news to him.

“It was my job to get the information out, but he had it before I did, on a regular – regular – basis,” Wright said. “I do not say this lightly, because I’ve worked with a lot of people I have tremendous respect for, but he is by far the best reporter I’ve ever been around. By far. I mean, he is relentless.”

Clare Farnsworth worked the Seahawks beat for the Post-Intelligencer during Clayton’s 11 years at the TNT. “I tell people I had a front-row seat for what John has become,” Farnsworth said. “I used to think that I wanted to print things that fans didn’t know; John said he wanted to print things that even the people in the building didn’t know.”

Farnsworth recalled an example of Clayton’s approach, often sprinting from the press room to follow coaches or execs out to their car at the old Kirkland, Wash., headquarters.

“We called it getting ‘Claytoned,’ ” he said, recalling a time when exec Mike McCormack tried to sneak out without Clayton seeing. “Mike got in his car really quickly and started to pull out, but John was trotting alongside, leaning in the window asking questions.”

Farnsworth grants that it was a nightmare to compete with Clayton for stories, but it produced a respectful friendship. “I always tell people that he deserves everything he’s gotten, even more, really,” Farnsworth said. “Because I know how hard he worked for it.”

While dogged, Clayton’s reporting was not without appropriate professional boundaries.

“I have tremendous admiration for him because he didn’t just go with (stories),” Wright said. “He might have the story but he wouldn’t go with it until he could verify it being absolutely right. He waited to be sure he had it nailed down … but he still beat everybody with it.”

If reporting is the craft, source-building is the art that fuels it. And the key is developing trust and respect.

“When you have a conversation with John, many times you’re learning something from him, too,” Polian said. “He’s extremely, extremely diligent, and extremely focused on facts and data. And this is something rare in the media business: He understands nuances, and can weigh all sides of a question.”

• • •

John Clayton grew out of the daily newspaper, where the restrictive news cycle was helpless to exploit the avalanche of NFL news he was breaking.

He started sharing information with ESPN in 1995, which gave him the immediacy he needed. He joined the network full time in 1998, feeding the digital explosion and the fantasy players’ cravings for instant, authoritative information on injuries and transactions.

He explains the method to his intense focus on contracts and roster status: “Why do I care so much about salaries? It gets into the logic of teams. It tells you what teams are thinking about their players. It tells you where they’re headed. It shows you trends in the league.”

At several points over the years, NFL teams tried to gauge his interest in serving as “a cap guy” for them, he said. But the fun, he said, is talking about it all in the media.

An ironic twist on Clayton’s buttoned-down image was the source of humor in the popular ESPN commercial. It shows him giving a standard informative NFL update. But when the camera is off, he strips off a mock suit-and-tie and pulls out a hidden ponytail to reveal himself as a thrash-metal rock fan living in his mom’s basement. He plops on the bed and starts digging his chopsticks into a container of leftover chow mein while head-bobbing to Slayer.

It was filmed not in his basement, but in a Los Angeles sound studio. “We had 65 people working on it,” he said. “We did 22 takes.”

Salituro said it’s considered the best of the ESPN commercial series.

Salituro was with Clayton in Canton, Ohio, in 2007 when Clayton was honored as the Dick McCann Award winner and participated in the annual events at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“They’ve got all the bands and floats in the parade, and here’s John in the back of a convertible waving to fans,” Salituro said. “People were yelling, ‘We love you, Professor,’ and ‘You’re the greatest.’ It was amazing.”

• • •

Sources interviewed on the topic of John Clayton always stress his extraordinary work habits.

“He’s the hardest-working guy I’ve ever known,” Wevurski said. “He wants to be the best NFL writer; he wants to be the best broadcaster. Whatever he’s doing, he wants to be the best.”

The Professor, himself, was asked the roots of his passion for the job.

“Well, you grow up in Pittsburgh, a steel town, grow up in a ghetto-like environment, you have a single mom who worked hard and did everything for you, and gave me that (example),” he said. “And then I was lucky enough to figure out from a very young age what I wanted to do. It’s worked out pretty well.”

Wright points to another element to Clayton’s advancement: his wife, Pat, a former clerk in the sports department at the News Tribune.

“Pat is the perfect complement for him,” Wright said. “She is really dedicated to him and he’s really dedicated to her. That marriage was made in heaven – or at least at the TNT.”

In recent years, Pat Clayton has fought the effects of multiple sclerosis. Her understanding of the demands of his job, and her support, Clayton said, is “100 percent” responsible for how far he’s come.

He has no interest in slowing his schedule, and, certainly, is unlikely to grow complacent.

“The one thing is, you always have to keep evolving and be open to different stuff,” he said. “You can’t get stagnant; it’s an ever-changing landscape.”

So, you have to stay hungry, to continue to be that bulldog reporter?

“Well, it’s not like I’ll bite anybody,” he said.

But if you had to for a story?

He squinted and shook his head … but not before giving the matter a moment’s thought.