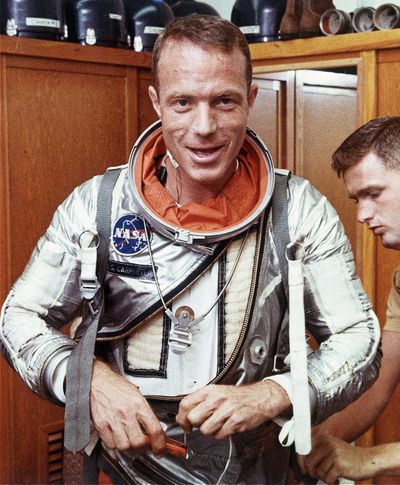

Original astronaut Scott Carpenter dies

After space, turned to sea explorations

DENVER – Scott Carpenter, the second American to orbit the Earth, was guided by two instincts: overcoming fear and quenching his insatiable curiosity. He pioneered his way into the heights of space and the depths of the ocean floor.

“Conquering of fear is one of life’s greatest pleasures and it can be done a lot of different places,” he said.

His wife, Patty Barrett, said Carpenter, 88, died Thursday in a Denver hospice of complications from a September stroke. He lived in Vail.

Malcolm Scott Carpenter was born May 1, 1925, in Boulder, Colo.

He followed John Glenn into orbit, and it was Carpenter who gave him the historic sendoff: “Godspeed John Glenn.” The two were the last survivors of the famed original Mercury 7 astronauts from the “Right Stuff” days of the early 1960s.

In his one flight, Carpenter missed his landing by 288 miles, leaving a nation on edge for an hour as it watched live and putting Carpenter on the outs with his NASA bosses. So Carpenter found a new place to explore: the ocean floor.

He was the only person who was both an astronaut and an aquanaut, exploring the old ocean and what President John F. Kennedy called “the new ocean”: space.

Even before Carpenter ventured into space, he made history on Feb. 20, 1962, when he gave his Glenn sendoff. It was a spur of the moment phrase, Carpenter later said.

“In those days, speed was magic because that’s all that was required … and nobody had gone that fast,” Carpenter explained. “If you can get that speed, you’re home-free, and it just occurred to me at the time that I hope you get your speed. Because once that happens, the flight’s a success.”

Three months later, on May 24, 1962, Carpenter was launched into space and completed three orbits around Earth in his space capsule, the Aurora 7.

His four hours, 39 minutes and 32 seconds of weightlessness were “the nicest thing that ever happened to me,” Carpenter told a NASA historian. “The zero-g sensation and the visual sensation of spaceflight are transcending experiences and I wish everybody could have them.”

Things started to go wrong on re-entry. He was low on fuel and a key instrument that tells the pilot which way the capsule is pointing malfunctioned, forcing him to manually take control of the landing.

NASA’s Mission Control then announced that he would overshoot his landing zone by more than 200 miles and, worse, they had lost contact with him.

Talking to a suddenly solemn nation, CBS newsman Walter Cronkite said, “We may have … lost an astronaut.”

Carpenter survived the landing that day.

Always cool under pressure – his heart rate never went above 105 during the flight – he oriented himself by simply peering out the space capsule’s window. The Navy found him in the Caribbean, floating in his life raft with his feet propped up. He offered up some of his space rations.

Carpenter’s perceived nonchalance didn’t sit well some with NASA officials, particularly flight director Chris Kraft.

Kraft accused Carpenter of being distracted and behind schedule, as well as making poor decisions. He blamed Carpenter for the low fuel.

On his website, Carpenter acknowledged that he didn’t shut off a switch at the right time, doubling fuel loss. Still, Carpenter in his 2003 memoir said, “I think the data shows that the machine failed.”

Carpenter never did go back in space, but his explorations continued. In 1965, he spent 30 days under the ocean off the coast of California as part of the Navy’s SeaLab II program.

Inspired by Jacques Cousteau, Carpenter worked with the Navy to bring some of NASA’s training and technology to the sea floor.

He retired from the Navy in 1969, founded his company Sea Sciences Inc., worked closely with Cousteau and dove in most of the world’s oceans, including under the ice in the Arctic.