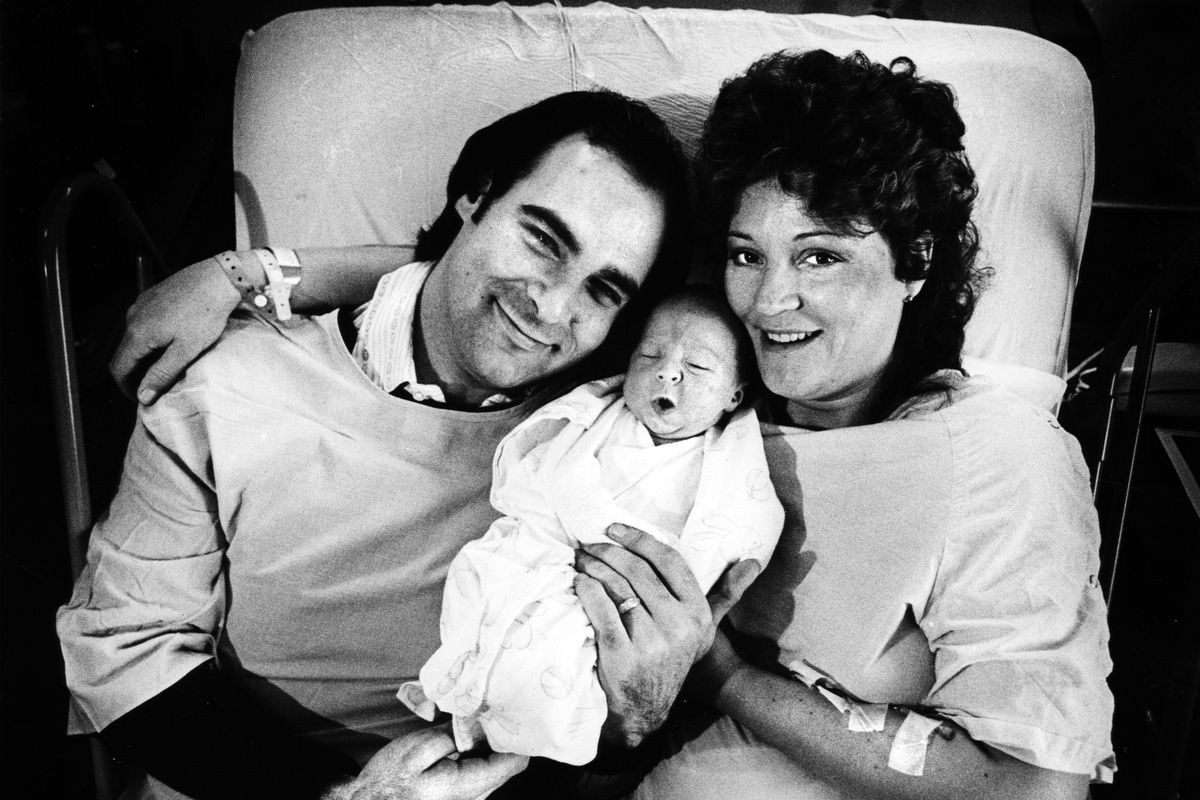

Spokane couple among nation’s first ‘test-tube’ parents

Thirty years ago this month, the first test-tube baby in the state was born in Spokane.

Though in vitro fertilization is now commonplace, in 1983 Kathy and Patrick Easter faced death threats and religiously charged accusations, and they ultimately left the area for jobs elsewhere.

The baby, Chris Easter, grew up to become a music promoter in Portland who backs shows all over the world “with the international message of PLUR” — peace, love, unity and respect.

Just a few months ago, Easter said, he was telling three young women friends in Portland that he was one of the nation’s first test-tube babies. “They were like, ‘Yeah, right,’ ” suggesting he was pitching an incredulous come-on line. That evaporated when one of the young women pulled out her smartphone.

“In just a matter of seconds, there it was on Google,” the Page One story from the May 11, 1983, edition of the Spokane Daily Chronicle, Easter recalled. “That made believers out of them.”

Fired from her job

While living in Spokane in 1983, the Easters’ decision to have a test-tube baby triggered a legal battle over unpaid sick leave, unemployment compensation and a mountain of medical bills. The Easters turned to in vitro fertilization (IVF as it’s called in the medical community) because her fallopian tubes had been removed following a tubal pregnancy. Still desiring a child, the couple turned to Dr. Bruce Hopkins, a Spokane obstetrician and gynecologist, for help.

After preliminary tests showed she had healthy, egg-producing ovaries and her husband’s sperm count was satisfactory, Hopkins referred the couple to the University of Texas Medical School, whose infertility experts were among the first researching test-tube births after the first in the United States in 1981.

Now retired after delivering 6,300 babies, Hopkins said last week he became aware of the procedure through his involvement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, later serving on its board of directors. “It’s now common, but it’s terribly expensive,’’ the retired Spokane obstetrician said.

“Most medical centers across the United States now have access to this procedure within their own institution,” Hopkins said.

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were more than 160,000 such procedures performed in the United States in 2011, the most recent data available. More than 61,000 babies were born from those procedures, and more than 1 percent of all infants born in the U.S. every year are conceived using “assisted reproductive technology.”

Insurance still generally doesn’t pay for the procedure, but federal and state laws now guarantee unpaid medical leave.

Back in 1983, at the Texas medical school, two eggs were retrieved from Kathy Easter and a sperm sample was collected from her husband. Conception occurred when the eggs and sperm were placed in a petri dish for several hours. Two days later, two fertilized eggs were placed in Easter’s womb during a brief medical procedure.

“The hardest part is you have to lie flat on your back for 24 hours,’’ Kathy Easter told the newspaper back in 1983.

She reflected recently, “Yes, that’s sure true.’’

Back in Spokane 11 days after the procedure, she conducted a self-administered pregnancy test and the results were positive. “I remember I was ecstatic,” she said.

Preconception costs alone – in 1983 dollars – were $6,800. Compounding things, two months after her pregnancy, Kathy Easter was dismissed from her job as a blood laboratory technician at Sacred Heart Medical Center. Her husband was honorably discharged in April 1983 as a senior airman survival instructor at Fairchild Air Force Base, but was unemployed with a pregnant wife.

News articles from 1983 say the hospital claimed at the time Kathy Easter was fired for refusing a job assignment, but she maintained her dismissal was related to her use of paid sick leave for in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that was criticized on religious grounds by some. The hospital also opposed her attempts to collect unemployment benefits, but Easter got those allotments after a brief legal fight.

On Oct. 24, 1983, the couple’s son was delivered by cesarean section at Deaconess Medical Center. The hospital later waived the couple’s medical bills associated with the birth, Kathy Easter recalled.

With their 8-month-old son, the Easters, both unemployed, moved to Brush Prairie, Wash., near Vancouver, where he took a job selling insurance. He later became a journeyman electrician while his wife pursued a medical research career with Kaiser Permanente in Portland and became a dog breeder.

International travel one of Easter’s interests

Despite the challenges, the couple say they don’t regret the experience for a minute and express pride in being among the first test-tube parents in the United States.

As a boy growing up in southwest Washington, Chris Easter became one of the youngest-ever student ambassadors, traveling to China, Japan, Germany and Holland, later becoming involved in the Model United Nations, Kathy Easter said.

He lived and attended school in Australia for six months as part of his unbridled interest in foreign relations and other cultures. He played football and basketball while attending colleges in Illinois and Oregon, and he still loves sports.

But now the former test-tube baby is driven by the repetitious electronic beat of house music – what some older folks might call the rebirth of disco. It’s the magnet that packs nightclubs.

Through his business “United2nite,” Easter now has business and Web ties with house-music promoters Hatiras and Deadmau5. Moving on from the rave scene, they organize and promote large dance parties in creative venues, such as cruise ships, warehouses, airplane hangars, roller rinks and bingo halls, along with a list of successful nightclubs.

After attending Benedictine University in Illinois, Chris Easter moved to Chicago and got interested in helping market the emerging house-music scene. Soon, he crossed paths with Chicago-based promoters and DJs Erik Johnson and Bobby DeMaria. “I saw gaps within the marketing,” he said.

“We ended up traveling the whole country, the world, for that matter,” Chris Easter said. The musical ties he’s made “is sort of like falling into a business partnership with Magic Johnson,” the basketball superstar.

Easter moved back to Portland in 2011 and within a month was promoting shows there. He also has a business promoting his clothing line, housemusicsavedmylife.com.

As a producer, he hires disc jockeys, sound and lighting techs and crowd control personnel. He currently produces “Madhouse Monday” at the Dirty Nightclub in Portland and just finished a successful cruise ship house-music promotion where partiers dressed as pirates. Now, he says, his goal “is to throw some of the biggest parties in Portland” with his house-music sounds.

Chris Easter says he likes to think he’s building bridges between his interest in international relations and the nightclub music scene.

“The message I like to spread at my shows is, ‘No matter what kind of trials and tribulations you may have had through the day, you can drop all that and feel a collective unity.’ That’s the vibe I give out – that we’re all part of the same family.”

Easter, who turns 30 on Oct. 24, is still “very close” to his parents, he said. His mother transported T-shirts for him last week from Chicago to Portland.

‘The best thing that ever happened to me’

The Easters never hid the facts of his conception from their son, even as a child. The topic still occasionally comes up. “I just tell people my mom and dad’s ‘workers’ got mixed in a petri dish and put back in my mother, and nine months later I was born,” Chris Easter said.

“It’s an ice breaker for sure,’’ he added. “The fact that I was one of the first test-tube babies is pretty cool.”

Kathy Easter, now 64, says it was all worth it, even with the death threats, hate calls and expense. Over the years, she has encouraged other infertile couples to explore the option of in vitro fertilization. She still has the petri dish used for her son’s conception.

“Chris was actually the best thing that ever happened to me,” his mother said.

She had one final word: “Please tell Dr. Hopkins I’d love to send him a picture of his 30-year-old ‘test-tube baby.’ ”