Seven Devils: Hikers approve of God’s work above Hells Canyon

Three seasons of major forest fires have remodeled the scenery for backpackers who might be revisiting Idaho’s Seven Devils Mountains for the first time in a decade.

But the Devils continue to be a heavenly destination for adventurers with the muscle power to get there.

The peaks remain tall, rugged and enticing to climb. Some 30 mountain lakes are still sparkling clear, the trout thick and feisty and the wilderness experience untamed.

Wildflowers and more expansive views of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area greet hikers in trail stretches that had been secluded in thick stands of timber before three consecutive fire seasons revised the landscape starting in 2005. Mountain goats and elk are easier to spot.

The Seven Devils Mountains cover nearly 60,000 acres roughly between Council and Whitebird, bordered between the Snake and Little Salmon rivers. They are the pinnacle of the 217,927-acre Hells Canyon Wilderness, which makes up about a third of the Hells Canyon National Recreation that straddles the Oregon-Idaho border.

The core cluster of peaks allows the claim that Hells Canyon is the nation’s deepest gorge – deeper than the Grand Canyon – if measured from the summit of He Devil Peak, elevation about 9,400 feet (sources disagree on a precise number) to the Snake River about 8,000 feet below.

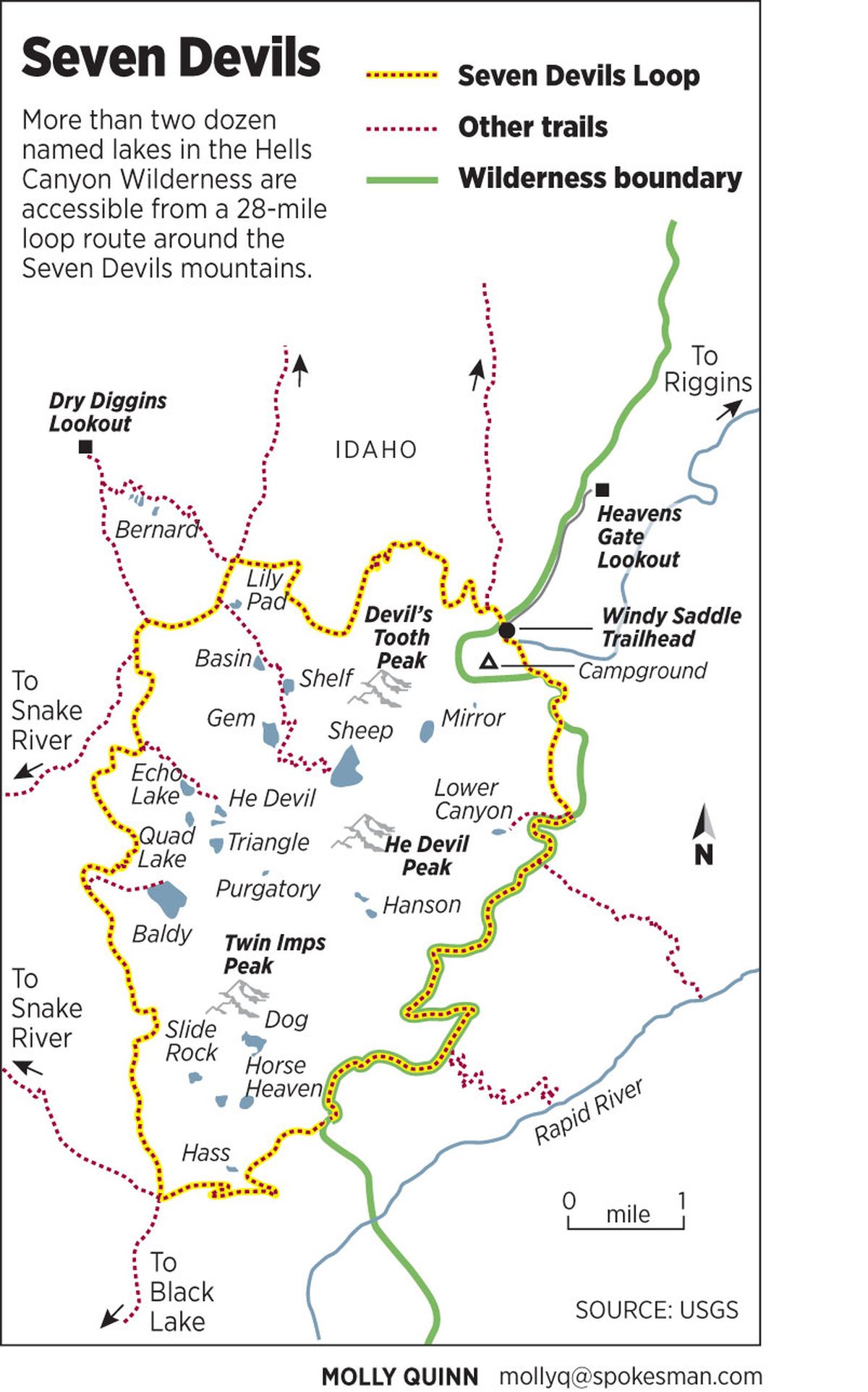

A 28-mile Seven Devils Loop, linking portions of Trails 101 and 124, circumnavigates the highest peaks with side-trip routes to two-dozen named lakes ranging in elevation from 7,100 to 7,900 feet. The loop can be hiked in two or three days, but the area demands at least five to seven days to be fairly explored and appreciated.

You only scratched the surface of the Devils if you have not strayed from the loop to climb a peak, bushwhack up to Dog Lakes or venture out to visit Dry Diggins Lookout site and the view all the way down the Snake River.

Hard-core hikers get the top –to-bottom “trip to Hell” experience by hiking the grueling switchback-trails that plunge from the Devils to the river.

The area is easy to access off U.S. 95 near Riggins by driving 17 miles up a road that gains 5,800 feet to Windy Saddle. Expect the trailhead parking area to be busy from the Fourth of July – if the road is clear of snow by then – through Labor Day.

However, Forest Service officials say the area does not suffer major impacts from users. No permits are required for hiking or riding stock into the wilderness. No sign-in registers are posted at.

“The area is accessible for only a short period when the snow clears to when the snow closes the road in late fall, so the use is focused but not to the point it needs to be regulated,” said Dan Ermovick, Wallowa-Whitman National Forest recreation planner in Baker City, Ore.

Most campers concentrate around lakes, although a contingent of hikers is lured by the potential to scramble up peaks such as He Devil and She Devil. Guidebooks describe several cross-country routes for hikers skilled at navigation over talus, scree and rotten-rock ledges through cols between the peaks.

But most hikers zero in on the 50-some miles of maintained trails in the Seven Devils, a fraction of the 208 miles of trails on the Idaho side of the Hells Canyon Recreation Area.

Timing affects the experience.

Hikers entering the Devils in early July will find snow in some areas. Also, they’ll beat trail crews dealing with the high number of blowdowns that come down on trails during the winter and spring.

“We’ve had a lot of forest fires in the past 25 years, with significant ones in the Hells Canyon Wilderness in 2005, 2006 and 2007,” said Kathy Conover, Forest Service trail maintenance leader out of Riggins since 1987. “That means a lot more trail maintenance. Lots of trees come down for 10-15 years after a fire.”

Conover and her crew needed four 10-day hitches to clear around 40 miles of main routes this year. Hikers who walked the Seven Devils Loop before the third week of July had some brief but serious tangles of blowdowns to negotiate.

“We didn’t finish clearing the loop until the end of July,” Conover said. “Even then you never know. A big storm came in a day after we pulled out and dropped 20-30 trees across Trail 101 near Horse Heaven overnight.”

Mid-September is a sweet time to be in the wilderness. Trails are cleared, mosquitoes are gone, fishing is good, most backpackers have ended their season and the major big-game seasons have yet to open and lure the fall influx of hunters.

Most of the elk and deer hunting activity is in Units 18 and 23, generally on and below Trail 101 (Boise Trail) along the wilderness boundary on the east side of the Devils. Few hunters use the west side lakes, where a fall hikers might find relative solitude with a few salt-poor mountain goats that frequent popular camping areas near Basin and Sheep lakes.

The name Seven Devils originates from Nez Perce Indian lore, according to most accounts. Others who followed maintained the theme as the peaks and lakes were named, notably by alpinists making first ascents in the 1930s.

Peaks including She Devil, Ogre, Goblin, Devil’s Throne, Mount Belial, Tower of Babel and Twin Imps scratch the sky above lakes such as Purgatory and Horse Heaven.

Considering that no one tapped options such as Limbo, Penance, Satan or Pearly Gates, one must assume the person who named Potato Hill didn’t have a clue that he was in what most trekkers would call Seventh Heaven.