Hanford ‘bomb factory’ talk of Reagan’s 1986 Spokane visit

Presidential visits to Spokane are always a big deal, but probably none was bigger than Ronald Reagan’s Halloween 1986 visit, when he came to a rally at the old Coliseum to help Slade Gorton’s re-election campaign defuse the “bomb factory” charge.

And may have cost Gorton his seat.

Gorton, a Republican former attorney general finishing his first term in the Senate, was locked in a tight race with Democrat Brock Adams, a former congressman and transportation secretary. At the white hot center of the race, at least from the Adams campaign standpoint, was the production of plutonium for nuclear weapons and the storage of nuclear waste at Hanford.

Adams had taken to calling Hanford a “bomb factory.” That played well in Seattle even as it riled the more scientifically literate in the Tri-Cities, who took pains to explain that Hanford did not make bombs; it made plutonium and other nuclear materials needed for warheads that were assembled elsewhere. Technically, they were correct, but politically Adams seemed to have a winner, particularly when coupled with the federal government’s ham-handed efforts to find a repository for decades of nuclear waste piling up around the country.

Original plans called for building two facilities to store the waste for about a bazillion years, one in the East, one in the West. But politics seemed to whittle options to a single site in the West, with one possible repository – or dump site, in Democratic campaign-speak of the time – at Hanford. Adams made campaign stops near railroad tracks and on overpasses around Spokane, telling folks that this is where the nation’s nuke waste would roll through if the Reagan administration picked Hanford.

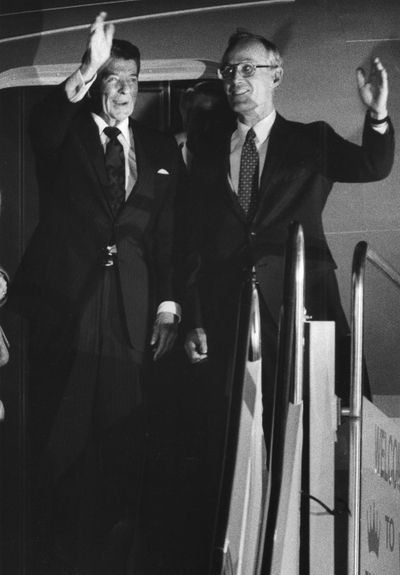

Gorton had criticized the U.S. Department of Energy for violating the law and pushed through an amendment to an appropriations bill that forbade test drills at Hanford for a possible repository. But Adams was scoring points in this Washington while Gorton was stuck in the other Washington. On Oct. 30, the Thursday evening before the election, Air Force One set down at Fairchild Air Force Base with Gorton on board, and a motorcade took him and Reagan to the Sheraton. The president went to his suite, but Gorton and Republican seatmate Dan Evans came down eventually to talk to the gaggle of reporters trolling for news on the ground floor. Gorton said he’d had “a more detailed discussion” than ever before about Hanford with the president on the way into town, but couldn’t say whether Reagan would mention the controversy in his rally speech the next day at the Coliseum.

Adams had campaigned most of the day in Spokane, at a factory gate, on downtown street corners and at a labor chili feed with Democratic Gov. Booth Gardner. He left town an hour before Reagan arrived, but not before he and Gardner essentially dared the president to say something about the controversy at the next day’s rally.

The gambit was clear. If Reagan announced a major policy shift, Adams could take credit for raising the issue. If Reagan said nothing, the campaign could accuse him of ignoring a vital state concern.

After Gorton’s comment that he’d essentially just had his first in-depth talk with the president about Hanford, the Adams campaign practically snorted with glee. They questioned what took him so long and invoked the name of Democratic icon Warren Magnuson – the man Gorton beat in 1980 – as someone who would have marched into the Oval Office if his state was being slighted on such an issue.

The day of the rally dawned with a new weapon for Adams’ campaign arsenal, a report the Energy Department was considering WPPSS 1, a mothballed commercial reactor at Hanford, to make nuclear weapons material.

Reagan had a reception before the rally for about a dozen people willing to shell out $5,000 for some face time and a photo. When asked about Hanford, he told a story about visiting a nuclear plant on the reservation in the ’50s when he was host of the General Electric Theater and GE was the main contractor there. He recalled setting off the radiation monitor visitors had to wear, and was told by a plant manager not to worry, it was just the radium dial on his watch. It wasn’t until he’d left the reservation, Reagan said, that he realized he wasn’t wearing a watch with a radium dial.

Asked about the process for selecting a repository site by The Spokesman-Review’s then-publisher William H. Cowles 3rd, Reagan told the group there had been some flaws with the process for selecting a repository, but didn’t elaborate. “I don’t know that there’s going to be any happy answer. No one wants it and I can understand that.”

At the rally, Reagan complimented Gorton, received a two-sided sweatshirt of Husky purple on one side and Cougar crimson on the other, and managed to flip the name of the state GOP chairwoman to Dunn Jennifer before launching into the stump speech designed to keep Republicans from losing the Senate for the first time in his presidency. He veered, if briefly, into Hanford, saying Gorton had gotten the ears of everyone in the other Washington about the repository: “I will see to it that the letter of the law is followed on this, and let no one tell you differently.”

A meaningless gesture, Adams and Gardner said almost as quickly as the campaign could fax out a response. The Energy Department has maintained all along it is following the law in naming Hanford a possible repository site, they said, forcing the state to sue the department to prove it isn’t.

Four days later, as Democrats retook the Senate, Adams beat Gorton by about 27,000 votes out of more than 1.3 million cast. Gorton won big in Franklin and Benton counties, the home of many Hanford workers, but not so big in Spokane – a margin of only about 3,200 votes compared to the 32,000 vote margin he’d had six years earlier. Adams won King County by 34,000 votes, where Gorton had beat Magnuson by 22,000. Exactly one week after the rally, Adams was back on Spokane street corners, thanking local voters for their support.

The political cognoscenti proclaimed Gorton’s political career over, but he proved far more resilient. Two years later, he won the seat vacated by Evans; he and Adams were seatmates. Gorton would serve 12 more years before being ousted by Maria Cantwell in 2000. He is the only person in state history to hold both U.S. Senate seats.

During his Senate term, Adams was accused by a series of women – former office staff, campaign volunteers and lobbyists – of sexual misconduct ranging from harassment to rape. He denied the accusations but retired from office in 1992.

Hanford eventually stopped making material for nuclear weapons but still has decades of Cold War waste sitting in underground tanks. Congress told the Energy Department to study only Yucca Mountain in Nevada for the repository in 1987, but the project remains tangled in politics.