This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Gains made by, for kids eclipsed by poverty

It sometimes seems that – in the realms where concerns about poverty and childhood are taken seriously – the news is always bad.

This is not because the news is always bad, however. And sometimes, in the push to address very real problems, underlying improvements go unseen. When that happens, the crisis mindset can begin to seem false or incomplete, eroding the very belief that we need, as a society, to try to address these problems to improve the lives of poor children.

And so the new Kids Count report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the annual statistical roundup of children’s health measures, provides reason for concern but also paints a picture of modest improvements on several fronts. In many cases, these improvements parallel government and educational efforts – the kinds of programs we are urged to believe never work.

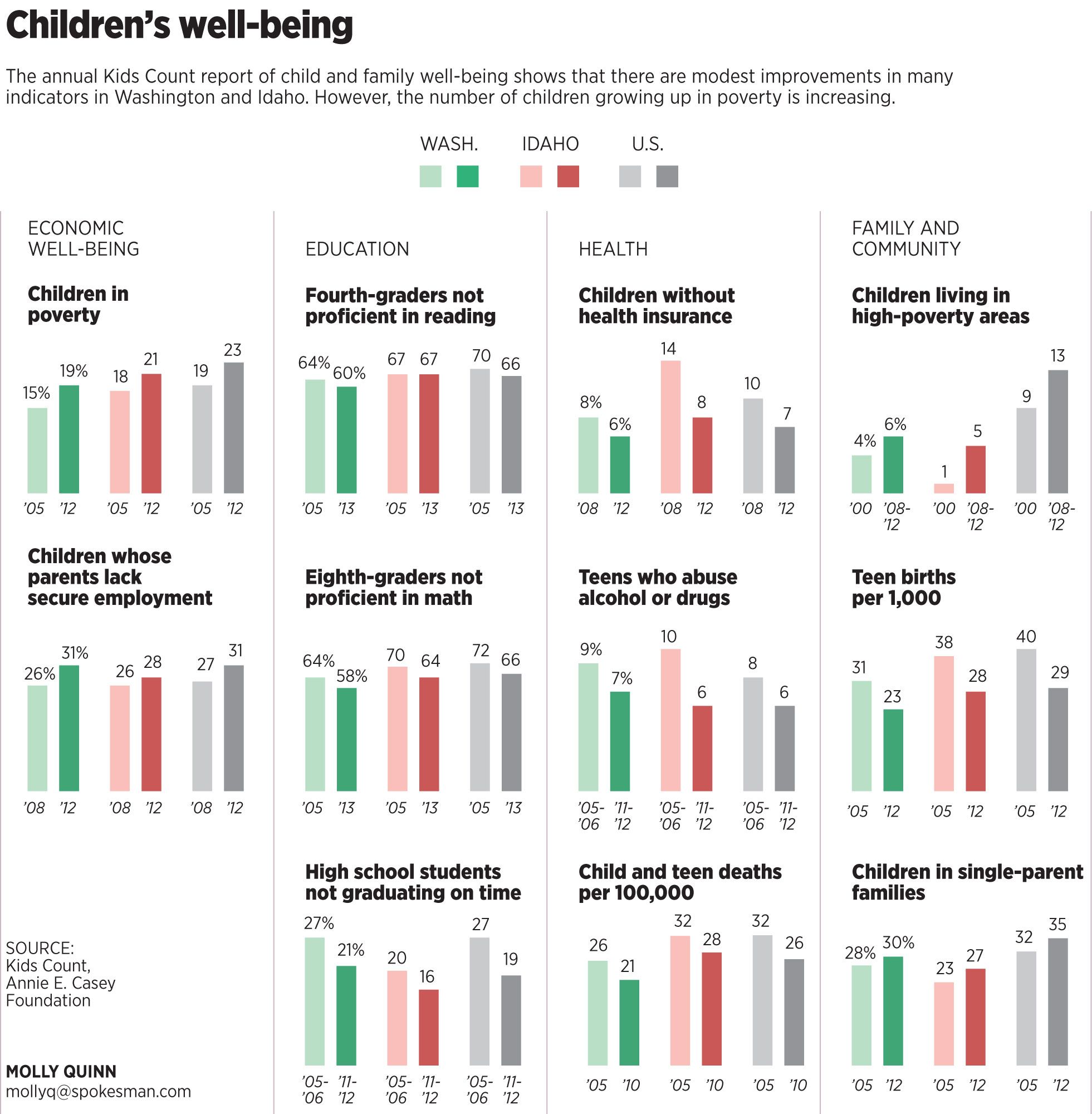

In both Washington and Idaho, more kids are attending preschool, fewer fourth-graders are failing reading tests, fewer eighth-graders are failing math tests, and fewer high school students are dropping out or not graduating on time. This is also true nationally, though in some cases the changes are awfully small.

On several health measures, there are similar changes. Fewer kids lack health insurance, and in Idaho this change is big: from 14 percent in 2008 to 8 percent in 2012. Teen births in Idaho are also way down, from 38 per 1,000 births in 2005 to 28 in 2012. In Washington, it dropped from 31 teen births per 1,000 to 23 over the same period.

Also, child and teen deaths are down, fewer teens abuse drugs and alcohol, and there are fewer low-birth-weight babies.

So – good news for some kids, and it’s the kind of good news that is really good for those individual kids who didn’t die or who attended preschool or who might have had an unwanted child at age 15.

But.

The Kids Count report is also a confirmation of the discouraging news about the country’s main wellspring of entrenched, multigenerational poverty: children growing up in poverty.

In 2012, 23 percent of American children lived in families making below-the-poverty-level income. That’s 16.4 million children. That’s an entire Netherlands of kids at risk for the lifelong problems that often follow children raised in poverty – including the high likelihood of adding another generation of impoverished kids.

The U.S. child poverty rate is an increase from 19 percent in 2005. Washington’s rate of children in poverty rose from 15 percent in 2005 to 19 percent in 2012. In Idaho, it went from 18 percent to 21 percent.

Also, more children live in entrenched high-poverty areas – in pockets where the deepest forms of poverty put kids at risk of the worst kinds of lifelong consequences.

“When a family experiences poverty, that comes with a whole host of issues,” said Lori Pfingst, research and policy director for the Washington State Budget and Policy Center. “Kids are less likely to do well in school, they’re less likely to live in a safe household. There are just all of these issues.

“When you have a whole community living in poverty … it moves beyond a family effect to a neighborhood effect.”

And Pfingst noted that among communities of color, the poverty figures are particularly stubborn: More than a third of black, Latino and Native American kids in Washington live in poverty. While she recognizes some of the gains reflected in the report, she emphasized that the worsening picture on child poverty remains an enormous long-term barrier to improving the lives of children and communities.

“If we could tackle that, we could see far more substantial gains,” she said. “And we’re just not doing it.”

Instead, the public discussion on poverty is often framed around the question of whether it even exists. There is a sustained political momentum behind the notion that poverty is a chimera – that there really are no poor Americans, just lazy people buying lobster with food stamps – and that programs to lift people out of poverty are some sort of political trickery by Democrats.

Wonderful variations of this kind of “thinking” are now a pandemic regarding the refugee children crossing the border. In what kind of country do politicians – like Idaho Gov. Butch Otter just did – score points by pre-emptively and proudly announcing they will not help children fleeing widespread violence, even when the politicians haven’t yet been asked to do so?

This ability to wrap the most callous and selfish indifference to the suffering of others inside a cocoon of logic and “Christian” belief is, perhaps, the deepest piece of the country’s dynamic in terms of long-term poverty. Pfingst said there are many policy steps that could go a long way toward improving the picture for poor children: an improving minimum wage, workplace policies that provide paid leave for parents in crisis or illness, and a rethinking of a regressive tax structure like Washington’s, which takes a disproportionate share of money out of the pockets of the poor.

But the first step would be to simply acknowledge it and believe in it. Two hundred eighty-eight thousand children in Washington state. More than an entire Spokane worth of children.

“When you have so many kids living in these conditions, it is not from personal failures,” Pfingst said. “It is systemic.”