Adventure writer Peter Stark to read at Auntie’s

As failures go, it was a glorious one, in Peter Stark’s estimation.

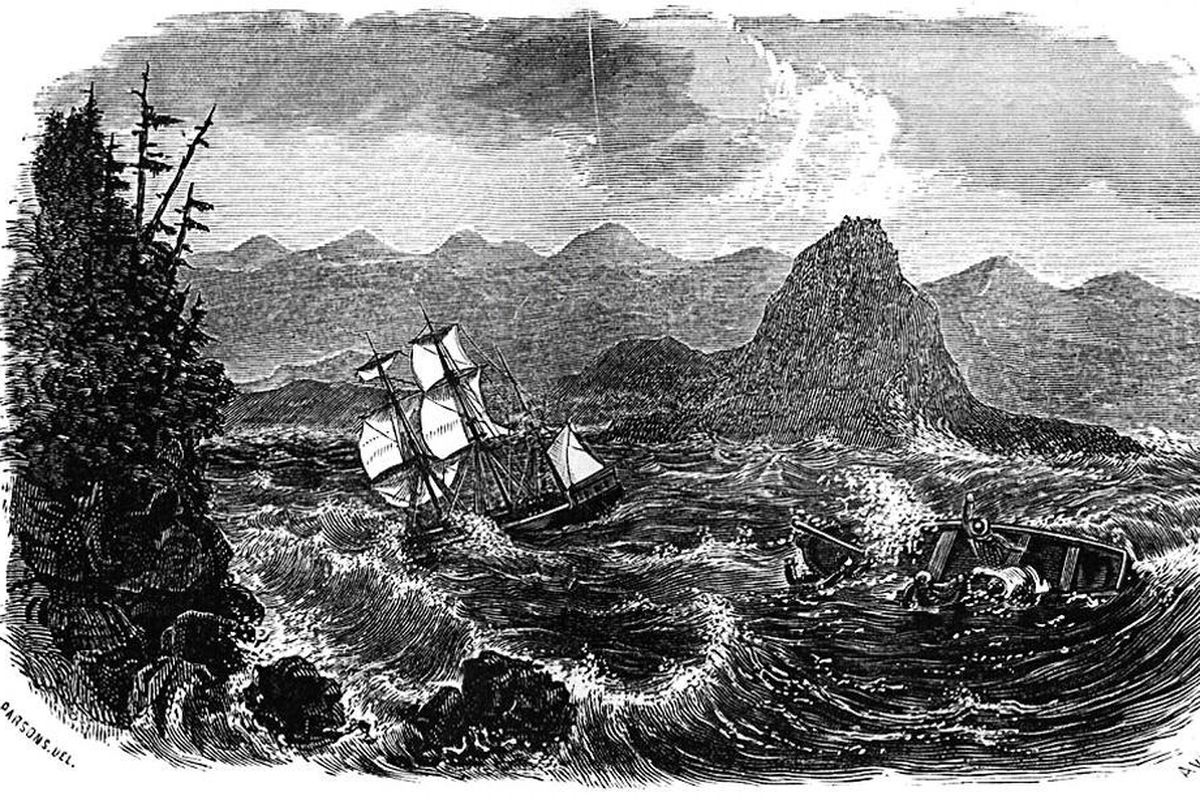

With sights on the Pacific Coast, one party of explorers set out by sea, a “shaggy bunch” of fur traders, craftsmen and clerks led by a rigid naval hero. As described in Stark’s book about their three-year westward expedition starting in 1810, pistols were drawn on the voyage’s first night over what time to put out the lights.

The second party sought to cross the continent by foot, horse, riverboat and canoe, led by a New Jersey businessman who’d never been to the wilderness before.

The would-be settlers were dispatched by John Jacob Astor, a millionaire who sought to create a trade network at the mouth of the Columbia River. Astor had backing from President Thomas Jefferson, who envisioned a separate, West Coast democracy that would spread east.

The Astorians set out five years after the Lewis and Clark expedition ended.

“At that point the West Coast was so remote and so distant and so wild that it was almost unimaginable to establish a colony there,” said Stark, whose book “Astoria” was published Tuesday.

Stark, a Missoula-based Outside magazine correspondent, will read from the book today at Auntie’s Bookstore as part of an Eastern Washington University visiting writers series.

Nearly half the explorers would die of violence along the way. And the survivors’ settlement was brief – Fort Astoria was sold in 1813 to the British, who didn’t completely vacate Astoria until 1846.

But the Astorians’ aim was ambitious and farseeing, Stark said. And their journeys – also marked by starvation, scurvy, cold-water immersion and other forms of high adventure – alerted Americans to the potential of the West Coast, he writes in his book.

“Stumbling around,” lost in the wilderness in search of the easiest route across the Rocky Mountains to the West Coast, the overland party found what would become the Oregon Trail.

“The continent changed, and these were the people who were on the forefront of that change – the very, very forefront,” Stark said.

Stark based his book largely on journals and memoirs written by party members and a book about the colony, also titled “Astoria,” by Washington Irving, commissioned by Astor and published in 1836.

Stark said he was drawn to the Astorians’ story partly because of his interest in how different personalities react to extreme stress.

His favorite Astorian: Marie Dorion, a pregnant Iowa Indian woman who traveled with the overland party with her two toddlers, “like Sacajawea but several times over,” Stark said.

Stark’s previous books chronicle his kayak expedition down Mozambique’s crocodile- and hippo-populated Lugenda River; his travels in Greenland and Iceland, where he encountered narwhal hunting and iceboat sailing; and the “blank spots” of the United States. “Last Breath” delves into extreme adventurers’ final moments.

The author grew up in Wisconsin, the son of a “great adventurous guy” – his father was a 1949 crewman on the last windjammer to sail around Cape Horn.

Stark opted out of the family candy-making business to become a writer.

“I thought I should write about the things I love doing,” he said. “And the things I love doing are adventurous things – travel to remote places and outdoor sports and indigenous people and things like that. Exploration.”

Stark and his wife, Amy Ragsdale, moved their family – their children are now 15 and 19 – to foreign locations for a year at a time, most recently a small town in Brazil.

Stark turned 60 in January. His interests remain the same as when he was 21, he said, but from a different angle.

“Now rather than doing the crazy adventures myself,” he said, “I’m more interested in writing about other people doing the crazy adventures.”