Washington confirms 4 new wolf packs

Annual survey finds continued steady expansion of wolves in Washington

Gray wolves established four new packs and expanded their territory in Washington over the past year, according to the annual status report on the state endangered species released Saturday by the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Biologists confirmed 13 wolf packs, five successful breeding pairs and at least 52 individual wolves based on surveys through the end of 2013.

The actual number of wolves is likely higher, said Donny Martorello, WDFW carnivore specialist.

Nine of the packs are in northeastern Washington with four along the east slopes of the North Cascades. Also, Oregon reports a new pack along the Washington border, bringing the number of Blue Mountains packs to at least two.

The first wolf pack in Washington in at least 70 years was documented in 2008.

The report was presented by state wildlife managers at the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission meeting in Moses Lake.

Wolf recovery has been accomplished and federal endangered species protections have been removed in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming.

However, the gray wolf remains protected under state endangered species laws throughout Washington and the species’ natural repopulation in the state is guided by state and federal recovery plans.

Federal law still protects wolves in the western two-thirds of Washington.

The state spent $531,913 on wolf management in 2013, including $177,898 for wolf conflict control, $140,855 for wolf capture and monitoring, $130,610 for radio collars, flights and contracts and $82,550 for outreach.

In 2012, the agency’s reported spending $750,000 for wolf management, including $76,500 for the extreme action of employing helicopter gunners to eliminate the cattle-killing Wedge Pack in northern Stevens County.

“While we can’t count every wolf in the state, the formation of four new packs is clear evidence of steady growth in Washington’s wolf population,” Martorello said. “More packs mean more breeding females, which produce more pups.”

All but eliminated from western states in the last century, the gray wolf was reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in the mid-1990s. Wolves have spread throughout most of the suitable habitat in the northern Rockies and are naturally moving into Washington and Oregon from Canada and Idaho.

Washington adopted a plan in 2011 that guides state management and recovery of wolves. The plan deals with restoring wolves and promoting coexistence while managing wolf-livestock conflicts and maintaining elk and deer herds that provide the wolf’s main prey base.

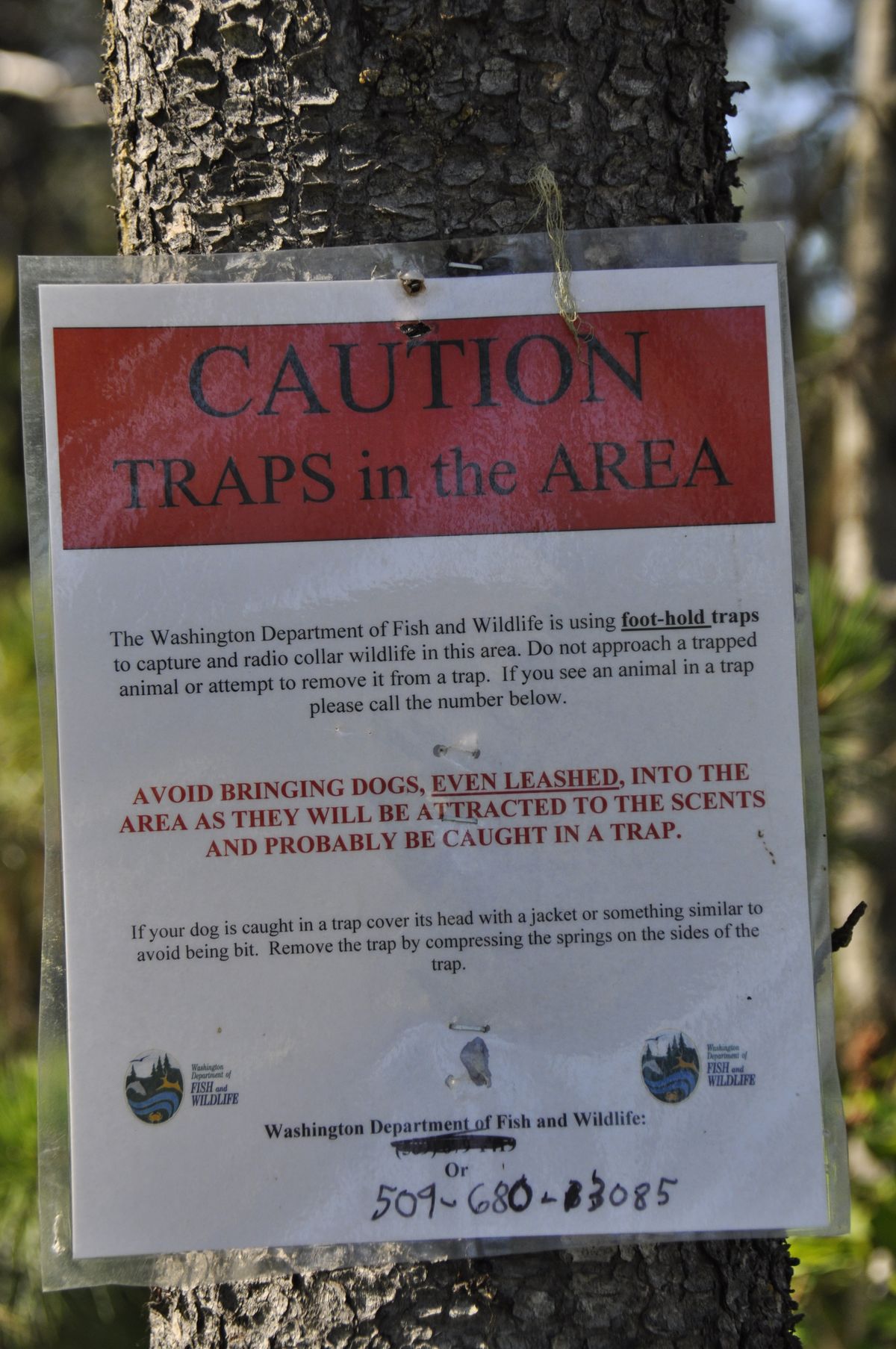

In developing its update, state biologists used aerial surveys, trackers and signals from 11 wolves wearing active radio collars, Martorello said.

Three of the new packs – Ruby Creek, Dirty Shirt and Carpenter Ridge – were formed by wolves that split off from the existing Smackout Pack in northeast Washington, he said.

A fourth new pack, the Wenatchee Pack, appears to be made up of two female wolves from the Teanaway Pack, whose territory stretches between Ellensburg and Wenatchee.

Under the state’s Wolf management plan, a wolf pack is defined as two or more wolves traveling together.

Despite their growing numbers, wolves were involved in fewer conflicts with humans and livestock in 2013 than in the previous year, Martorello said.

Stephanie Simek, WDFW’s wolf conflict-resolution manager, said the department investigated 20 reported attacks on pets and livestock last year, but found that wolves were involved in only four of them. Confirmed wolf attacks left one calf dead and three dogs injured, she said.

In 2012, wolves in Washington killed at least seven calves and one sheep while injuring six additional calves and two sheep, Simek said. Most of those attacks were made by the Wedge Pack on a single rancher’s cattle in northern Stevens County, she said.

The agency ultimately killed seven members of the Wedge Pack to stop the escalating series of attacks. Two wolves were still travelling as a pack in the same area in 2013, she said.

“That was an extraordinary event that we do not want to repeat,” said Martorello, noting that no wolves were killed by WDFW last year.

Five wolves are known to have died in 2013. Causes range from a car accident on Blewett Pass to a legal hunt on the Spokane Indian Reservation, where the tribe is not subject to state endangered species rules.

The case of a wolf illegally killed this winter is being investigated in northern Stevens County. A $7,500 fine is being offered for the radio-collared wolf found shot to death on Feb. 9.

Simek outlined steps the state has taken in the past year to reduce conflicts with wolves, such as:

Cooperative agreements: 29 livestock producers entered cost-sharing agreements to take proactive steps to avoid conflicts with wolves. Strategies include improving fencing and sanitation, employing range riders and using non-lethal hazing methods to repel wolves.

Increased staffing: Seven new staffers were hired for a new 13-member Wildlife Conflict Section dedicated to working with livestock producers, landowners and entire communities to avoid conflicts with wolves and other wildlife.

Wolf advisors: A nine-member advisory group was established to recommend strategies for encouraging more livestock owners to enter into cooperative agreements, providing compensation for wolf-related economic losses and other issues. Members of the group represent hunters, livestock producers and conservation groups.

“These actions have greatly improved the department’s ability to manage our growing wolf population and meet state recovery goals,” Martorello said.

Wolves can be removed from the state’s endangered species list once 15 successful breeding pairs are documented for three consecutive years among three designated wolf-recovery regions – or 18 successful breeding pairs in one year among three designated wolf-recovery regions.

A successful breeding pair is defined as an adult male and female with at least two pups that survive until the end of the year.

In 2013, biologists documented three successful breeding pairs in the Eastern Washington recovery region and two pairs in the North Cascades region.

No wolf packs or breeding pairs have been found on the South Cascades/Northwest Coast region.

Meanwhile, the federal listing of gray wolves under the Endangered Species Act is currently under review.

In June, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed delisting gray wolves nationwide. A decision is expected this year.