Kostelecs use historic equipment to create original images

Bill and Kathy Kostelec are old-school photographers. Really old school.

To make their black-and-white photographs, the Kostelecs – a married couple whose work will be featured at a show opening Friday – load single sheets of film into big, bulky, wood and metal cameras dating as far back as the early 1900s.

They tote loads of equipment, including heavy film holders, a bellows for focusing, a collection of lenses, and a dark cloth to block the sunlight from their eyes as they focus on their subjects.

There’s no deleting the images they don’t like, and each piece of film is processed individually or, at most, six at a time in the darkroom behind their house in south Spokane.

As most professional photographers have turned to digital cameras for their speed and convenience, film still appeals to some artists for its ability to convey details, texture and tones, Bill Kostelec said.

“What we do, nothing is done for you. You have to do everything by hand,” he said. “You can make a hundred mistakes from shooting to get it in the darkroom to getting a finished print. It doesn’t work every time. But when it does work, we feel like we earned it.”

The Kolva-Sullivan Gallery show will showcase the pair’s contact prints, made using direct contact between a negative and a piece of printing paper.

The Kostelecs’ equipment and techniques yield a remarkable image quality, said Jim Kolva, who owns the gallery with his wife, Pat Sullivan. But the images are more than recordings, offering what seems to be a shared point of view.

“They’re able to capture the essence of something and put it into a different light,” Kolva said. “That’s true of their landscapes as well as their images of people and urban scenes.”

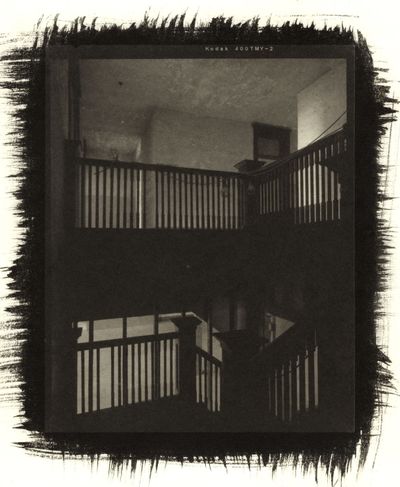

Kolva remembered seeing one print – a photo of an old changing-room entrance at Witter Pool – before he’d met the Kostelecs.

“It had kind of a softness and a little bit of a sense of mystery to it,” he said. “… They have this little bit of mystery, like ‘What’s going on here? Why are they showing us this image?’ It gives you room to think about it.”

The show of roughly 80 photographs was curated partly as a “celebration,” Kathy Kostelec said, of the expanded possibilities made possible by the recent construction of their darkroom, allowing them to process and print their own photos and experiment with paper and toning techniques.

But it all starts with the film. Larger film can capture more information. Images made on big pieces of film can produce striking results even after they’re enlarged.

A 24-by-28 enlargement of that 1912 changing-room entrance, blown up from an 8-by-10 negative, shows the brick and wood in intricate detail. Its crispness and sense of depth renders it almost three-dimensional at first glance.

“Black and white photography – it’s reduction,” Bill Kostelec said. “It’s a sort of an unreality to start with. It’s like drawing something in charcoal. So you have to concentrate on mass, the solidity of things. And you concentrate on textures, and the way light falls on things.”

The couple shoot buildings and other structures, landscapes and portraits.

Using photography as an excuse to explore, Kathy Kostelec said, they’ve traveled in the Northwest, Midwest and Southwest in search of subject matter. They’re planning a trip this spring with stops in Yosemite National Park and Death Valley. They also travel in Spokane and Eastern Washington, where they’ve shot landmarks now shuttered: the shut-down barbecue joint Sam’s Pit, the Lucky Penny bar.

“If something catches your eye, you should shoot it, because you never know if it’s going to be the same again,” Kathy Kostelec said, sitting at her dining room table, the brightly painted walls around her lined with framed black-and-white prints. “So many things that we have on the walls of this house are gone or forever changed.”