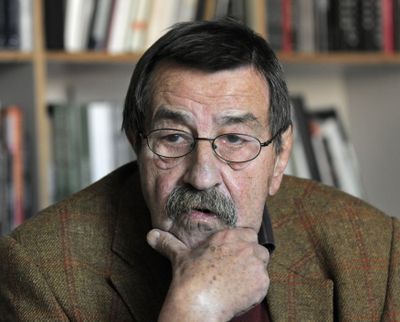

Author, Nobel laureate Guenter Grass dies at 87

BERLIN – Guenter Grass, the Nobel-winning German writer who gave voice to the generation that came of age during the horrors of the Nazi era but later ran into controversy over his own World War II past and stance toward Israel, has died. He was 87.

Matthias Wegener, spokesman for the Steidl publishing house, confirmed that Grass died Monday morning in a Luebeck hospital.

Grass was lauded by Germans for helping to revive their culture in the aftermath of World War II, and giving voice and support to democratic discourse in the postwar nation.

“His literary legacy will stand next to that of Goethe,” German Culture Minister Monika Gruetters said in a statement following the news of his death.

Yet Grass provoked the ire of many in 2006 when he revealed in his memoir “Skinning the Onion” that, as a teenager, he had served in the Waffen-SS, the combat arm of Adolf Hitler’s notorious paramilitary organization.

In 2012, Grass also drew sharp criticism at home and was declared persona non grata by Israel after publishing a prose poem, “What Must Be Said,” in which he criticized what he described as Western hypocrisy over Israel’s nuclear program and labeled the country a threat to “already fragile world peace” over its belligerent stance on Iran.

A trained sculptor, Grass made his literary reputation with “The Tin Drum,” published in 1959. It was followed by “Cat and Mouse” and “Dog Years,” which made up what is called the Danzig Trilogy – after the town of his birth, now the Polish city of Gdansk.

Combining naturalistic detail with fantastical images, the trilogy captured the German reaction to the rise of Nazism, the horrors of the war and the guilt that lingered after Adolf Hitler’s defeat.

“The Tin Drum” follows the life of a young boy in Danzig who is caught up in the political whirlwind of the Nazi rise to power and, in response, decides not to grow up. His toy drum becomes a symbol of this refusal.

The books return again and again to Danzig, where Grass was born on Oct. 16, 1927, the son of a grocer.

In the trilogy, Grass drew partly on his own experience of military service and his captivity as a prisoner of war held by the Americans until 1946.

“The Tin Drum” became an overnight success – a fact that Grass told the Associated Press in 2009 surprised him. Asked to reflect on why the book became so popular, he noted that it tackles one of the most daunting periods of German history by focusing on the minutiae in the lives of ordinary people.

Then he quipped: “Perhaps because it’s a good book.”

Three decades after its release, in 1999, the Swedish Academy honored Grass with the Nobel Prize for literature, praising him for setting out to revive German literature after the Nazi era.

With “The Tin Drum,” the Nobel Academy said, “it was as if German literature had been granted a new beginning after decades of linguistic and moral destruction.”

“His writing had a great political significance, especially in the renaissance of Germany after the World War,” 1991 Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer told the Associated Press in 1999. “He never failed to confront Germans with what they did.”

Grass untiringly warned his compatriots to remain vigilant against racism.