Commentary: Dean Smith was the real thing

After the games, back in the glory years when Dean Smith was coaching college basketball better than anyone on earth, he would stand in the dim hallways outside the locker room and consider the postgame questions with a cigarette cupped in one hand and a profound distrust rolled tight in the other.

It was long before the ritual was moved to sterile, televised sessions at a podium, a distant predating of the time when every uttered word would be thumb-typed around the world immediately in 140-character bursts that record everything but explain nothing.

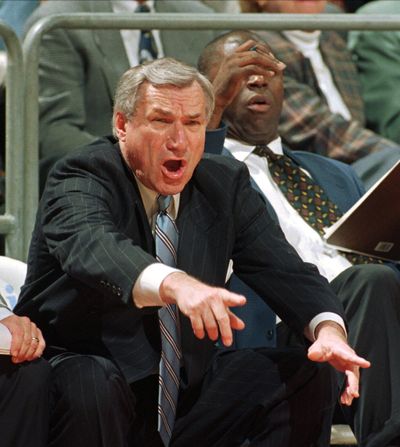

Smith was not an easy man to like in those settings. He was as defensive as his teams, and sometimes just as offensive, too. The questions came and Smith would draw on the smoke that was pinched between his thumb and forefinger until it brightened the palm of his hand and made the sharp, hawkish features of his face glow in reflection.

“If you knew the game of basketball, you would know that’s not really the case,” Smith would say, or something of the sort, as he swatted an implied criticism out of bounds.

Dean Smith was a heavyweight in a profession that produces a lot of people who think they are. He was the real thing, though, and he knew it.

Smith’s reputation didn’t come from the outside, but brick-by-brick within the confines of Chapel Hill until it became an edifice as imposing as the man himself. He certainly had players, but there’s a reason he had players. It was because North Carolina won, always won, and the lucky ones who were recruited and went through the system became winners, too, and were prized at the next level of the game, either as players or coaches themselves.

There was innovation in what North Carolina did, as you would expect from a man only two degrees removed from the very invention of the game. Smith, a son of Kansas schoolteachers, played for Phog Allen, who, in turn, had played for Dr. James Naismith. The Tar Heels based their philosophy on a smart, motion offense and aggressive trapping defense, but so do a lot of other teams. Smith just had his players do it better than everyone else and won a tick under 78 percent of his games over a 36-year career. Carolina won two national championships and went to the Final Four 11 times, the first in 1967, the last in 1997.

The constant over the years was Smith’s combativeness and his reflexive dismissal of others’ methods. There was the “Carolina Way,” and it was the only right way, and if outsiders thought that was a little much, well, check the scoreboard. Players who scored were taught to point out the teammate who made the pass, and to remove themselves on the honor system if they grew tired. They were coached to accept a team concept so rigid that it was said, quite accurately, that Dean Smith would be the only force in basketball ever capable of holding Michael Jordan to fewer than 20 points per game. (Jordan averaged 17.7 points in 101 games for Carolina despite shooting 54 percent.)

Smith’s rigidity and his dedication to doing the right thing extended far beyond basketball, and his other legacy was his ability to champion causes in the state of North Carolina that would have scared off those with lesser resolve.

Along with a black minister and black theology student, he integrated a Chapel Hill restaurant in 1964 and it stayed integrated. He broke an accepted color barrier and recruited Charlie Scott, the first black scholarship athlete at the school, in 1966. He was a critic of the war in Vietnam, supported a ban on nuclear proliferation and made sure that when a female sportswriter was assigned to his team by a local newspaper that she was accorded the same treatment as everyone else.

These were not – and still aren’t, to some degree – popular stands in North Carolina, but Smith was never interested in popularity. He wanted the game to be played properly on the court, and wanted life to be just as orderly away from it.

His strongest stand later in life was against the death penalty. The Tar Heels would occasionally be loaded onto buses and taken to the prisons to hold practice in front of an audience that included the condemned in their orange jumpsuits. On the way back to campus, the bus was quiet.

Again, Smith was probably the only man in the state who could have been as active in that sort of cause and still remain universally popular. People who didn’t agree respected the moral underpinnings of his stance.

That’s a remarkable life that ended Sunday just weeks before Smith’s 84th birthday. He had slipped into dementia in the last few years and little remained of the sharp mind.

Living is a lot harder than dying, though, and Dean Smith didn’t take shortcuts. Looking back across the glowing embers of his career, the memory of his way of doing things, which also became the Carolina Way, still sparks to life and illuminates the man who narrowed his eyebrows and curled his lip and was very sure he was right.