Fear of cross-border measles unfounded

Countries south of U.S. share high vaccination rates

Conservative radio commentator Rush Limbaugh and others have blamed the current measles outbreak on children illegally crossing the southern border of the U.S.

“Children sick, healthy, you name it – poor, ill-educated, just tens of thousands of kids flooded the southern border all of last year,” he said. “They were never examined before they got here. They were never examined after they got here and quarantined if they had a disease. They were just sent out across the country. Many of them had measles.”

While there are many serious diseases that have moved north to the United States from Mexico and Central America, measles is not one of them.

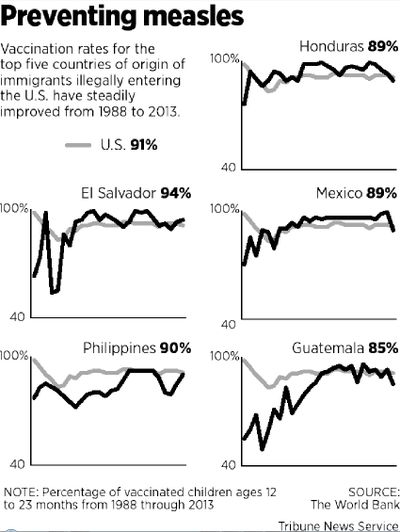

Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras all have measles immunization programs comparable to the United States, making them unlikely sources of the outbreak.

According to the latest figures from the World Health Organization, the U.S. in 2012 had a measles vaccination rate of 91percent; Mexico’s was 89 percent, El Salvador’s 94 percent, Guatemala’s 85 percent and Honduras’ 89 percent.

In this latest outbreak, measles has actually spread from the United States to Mexico, which has reported one case from exposure at Disneyland, the apparent epicenter of the outbreak.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that the genotype of the measles virus in this country is identical to one that caused a serious outbreak in the Philippines in 2014.

In 2013, the CDC recorded 42 cases of measles that were brought into the U.S. from overseas. Of those, half of the infected people came from the World Health Organization’s European region, which covers Europe and parts of central Asia.

A particularly large outbreak that year in North Carolina involving 22 people was traced to an unvaccinated person who had traveled to India.

Beyond measles, however, there are some serious diseases that are brought to the United States from Mexico and Central America. Chief among them is tuberculosis.

In 2013, 65 percent of the tuberculosis cases in the U.S. occurred among foreign-born people, according to the CDC.

A majority of those people came from five countries: Mexico (1,233 cases), the Philippines (776 cases), India (495 cases), Vietnam (454 cases) and China (377 cases).

“The foreign-born population has the bulk of TB cases, but they’re not really spreading it beyond their communities,” said Dr. Stephen Waterman of the CDC’s U.S.-Mexico unit in the division of global migration and quarantine.

“I think it’s very safe to say that immigrants coming into the United States are not transmitting new diseases to the general population in any way that is of important public health concern,” he said.

Overall, tuberculosis rates are higher in Asia and Africa than they are in Mexico and Central America, Waterman said.

Tuberculosis, an airborne disease, was a leading cause of death in the U.S. about a century ago, according to the National Institutes of Health. Since 1992, the number of cases reported annually has been decreasing, the CDC said.

Hepatitis A is another concern. Mexico and Latin America do not routinely vaccinate for hepatitis A and so have higher infection rates, Waterman said. Between 2000 and 2009 along the southern border, a CDC study found the rate of infection was more than three times higher in Mexico.

Infectious disease is a key concern of the Border Patrol. Immigrants detained along the border are all subject to a health screening, said Border Patrol spokesman Carlos Lazo.

Immigrants who are turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement receive a medical, dental and mental health screening within 12 hours of arriving at a detention facility, spokeswoman Virginia C. Kice said.

Within two weeks all detainees receive a comprehensive health assessment, both physical and mental, she said.