Meeting of the minds, literally: Brain experiment could boost medicine

SEATTLE – Brain scientists at the University of Washington have used an old-fashioned parlor game in a novel way to prove that two people’s brains can be linked across the Internet – an experiment that sounds like it was ripped from the pages of a science-fiction novel.

The experiment is believed to be the first one to demonstrate that two brains can be directly linked to allow one participant to correctly guess what the other is thinking.

Researchers say melding two minds has the potential for a vast range of applications. For example, it might allow for the transfer of information from a healthy one to a damaged one. Or it might allow an alert person to transmit that brain state to somebody who is sleepy, or struggling to pay attention.

“What we wanted to establish is that it is possible to use this rudimentary brain-to-brain collaboration … to solve a common problem,” said Andrea Stocco, an assistant professor of psychology and researcher at the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences at the UW.

The research was published recently in the journal PLOS ONE. The brain-science investigations are funded by a $1 million grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation.

Researchers used “20 Questions,” a guessing game in which one person thinks of an object and the other tries to guess what it is with a series of 20 or fewer questions that can only be answered by “yes” or “no.”

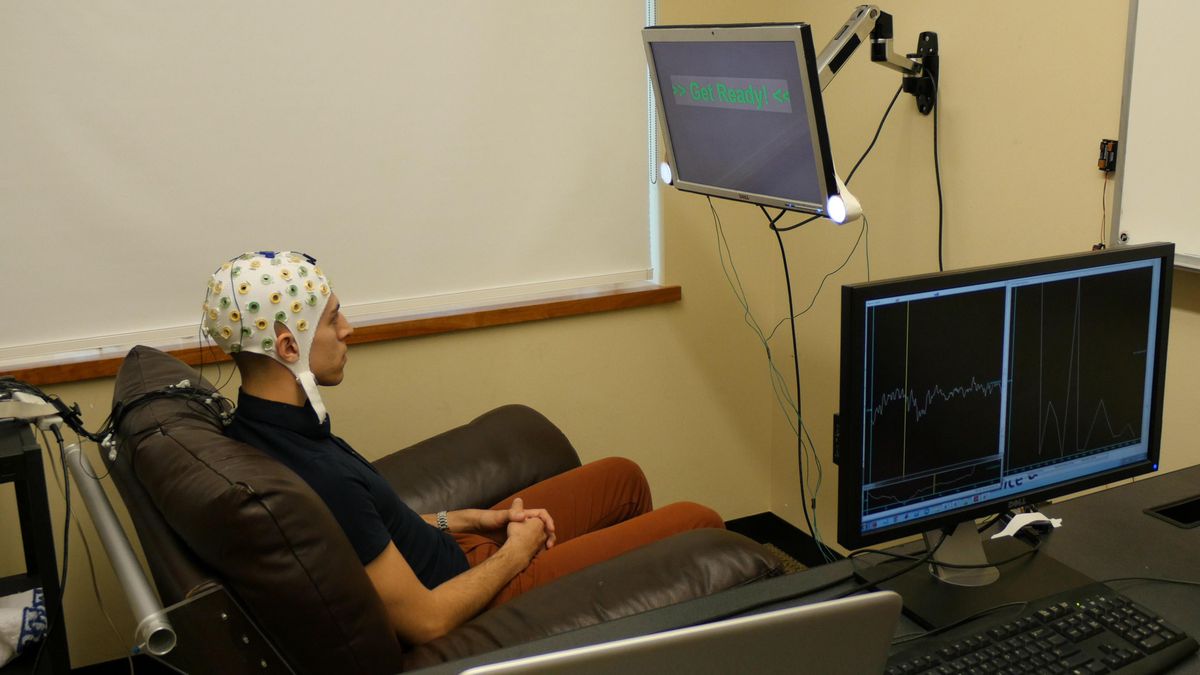

In the experiment, two participants played the game in rooms a mile apart on campus. One participant wore an electrode-studded cap connected to an electroencephalography machine to pick up signals from the brain.

The other wore a cap with a magnetic coil positioned over the part of the brain that controls the visual cortex.

The player wearing the electrode cap picked an object, and the player wearing the electric coil asked a series of questions to try to guess the object. The electrode-capped player signaled to the questioner whether the answer was “yes” or “no” simply by looking at a flashing light that indicated the answer. A “yes” sent a signal to the questioner; a “no” sent no signal at all. The signal was transmitted via the Internet.

If the answer was yes, the brain activity in the first player’s brain delivered a signal to the electric coil worn by the second player, which translated into a visual interruption or flash of light known as a “phosphene.”

Stocco said it took trial-and-error to position the magnetic coil so that it reliably transmitted a signal to the player asking the questions. And not everyone saw the same visual interruption.

“I consistently saw lines,” Stocco said. “Some saw lightning bolts, blobs or shapes.”

Stocco said the success of the experiment took researchers by surprise.

“We knew in theory it could work,” he said. “We wanted to know how well it could work.”

Subjects arrived at the correct answer in the 20 Questions game 72 percent of the time; to do that, they answered more than 90 percent of the questions correctly. In other words, they saw the visual interruption, and interpreted it as a “yes.”

Five sets of participants played 20 rounds of the game – a mixture of 10 real games and 10 control games, in which no visual signal was sent at all. Participants guessed the correct answer only 18 percent of the time in the control games.

It’s not the first time Stocco and his fellow researchers have delivered a brain-to-brain signal over the Internet. Two years ago, Stocco and computer-science professor Rajesh Rao conducted an experiment in which Rao transmitted signals from his brain to Stocco, causing his finger to twitch.

At the time, the two said they believed it was the first time two human brains had been directly connected in this manner. However, some neuroscientists dismissed the experiment as a publicity stunt.

Stocco said researchers hope they’ll eventually be able to transmit more complex signals, such as shapes rather than simple flashes of light.

In the 20 Questions experiment, “the brain is trying to make sense of a signal that normally doesn’t exist,” he said. “The brain is saying, ‘I don’t know what this thing is, but I think it’s a line.’ If we can control that with more precision, we could make a shape, or an object.”

If scientists could figure out how to transmit shapes between two brains, it might eventually allow people to collaborate on problem-solving in a completely novel way, he said.

Stocco said there are other applications for the science, too.

For example, researchers know how to measure patterns of brain activity to tell whether somebody is paying attention. One day, scientists may be able to capture those brain patterns and transmit them to a person whose mind wanders, such as a student trying to overcome attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Or perhaps one day, you could record the electrical impulses that pulse through your brain when you are at the peak of performance, and use that to wake up your brain at a later state, when your attention is flagging.

“It could be a new frontier of self-help,” Stocco said.