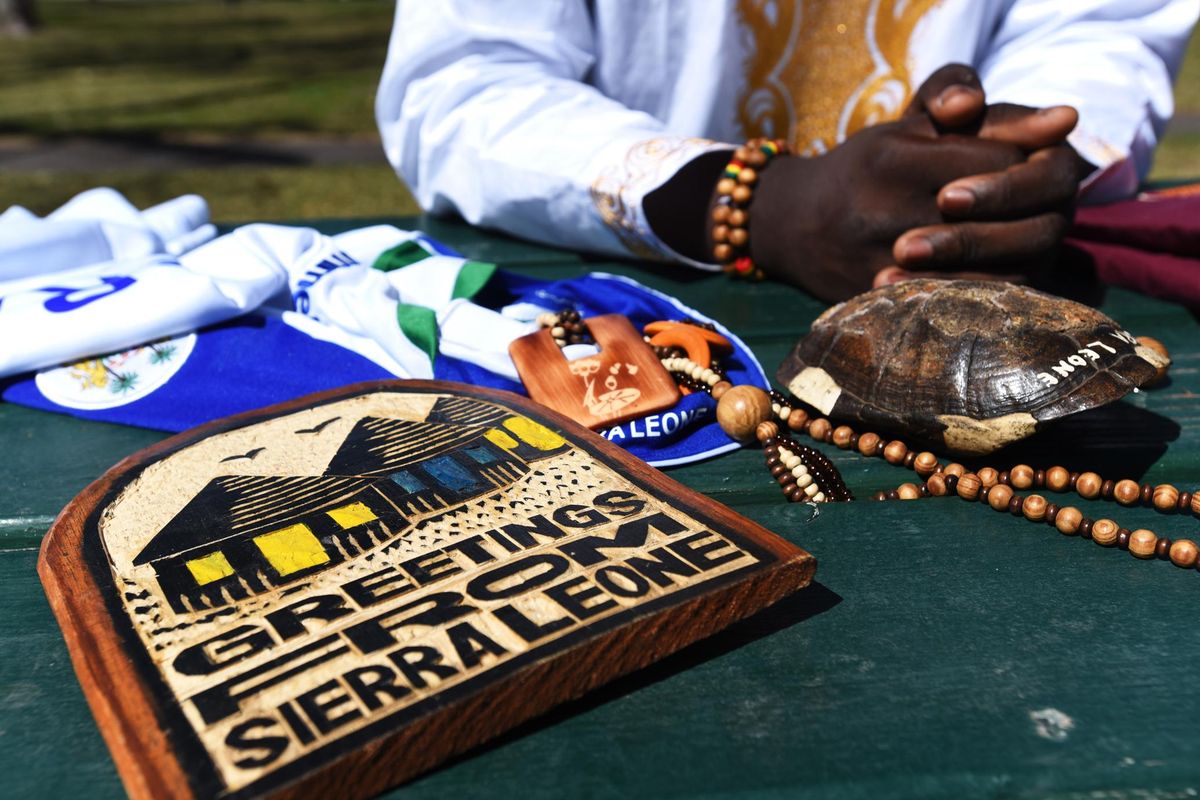

Montana man delivers water filters to his native Sierra Leone

MISSOULA – Usifu Bangura felt his skin vibrate when he stepped off the plane in Freetown and the 90-degree air pummeled his body.

“That’s where my skin feels best,” said Bangura, a native of Sierra Leone.

But when the Missoula man awoke in the morning and looked across the city of nearly 1 million, the poverty struck him, the Missoulian reported.

“This is where my mother wanted to take me away from. It opened my eyes a lot more,” said Bangura, wearing a hand-embroidered shirt from Sierra Leone.

Bangura arrived back in Montana from a month in the small West African country where his mother gave him up for adoption in 2004. Eventually, he landed in Montana, and last year, after learning about the Ebola crisis, he pledged to return to Sierra Leone to take water filters and discover other ways to help.

He not only fulfilled his mission overseas, he has a team including a lawyer and professionals working in international development ready to help him set up a nonprofit, the Bangura Project, to continue the work.

“I really want to put my heart and soul into this nonprofit and this project,” Bangura said.

In Sierra Leone, he ate much rice and cassava, bobbed and weaved through traffic in a place with no road system, and found appreciation for all the things his life in the U.S. has given him that he wouldn’t have in Africa.

“I’m thankful of the resources I have here and the opportunities I was given here,” he said.

At first, Bangura didn’t know if he’d find his mother alive, but he connected with Fatu Fhanko prior to his trip, and he also learned of an older brother he didn’t know he had. His mother had given him up for adoption along with a couple of younger siblings who also landed in the United States.

In March, Bangura’s older brother, Ibrahim, met him at the airport, and they had a moment of understanding when they locked eyes. Bangura is tall, and his brother is short from malnutrition, but they recognized each other as family.

“We laughed when we first saw each other,” said Bangura, 19.

A couple of days later, after a three-hour cab ride to the village of Mambolo, he embraced his mother for the first time since he left Sierra Leone.

“We hugged each other a lot. It’s one of those things I can’t get out of my head,” Bangura said.

Then, he asked her a question.

“Where do you get your water?”

“Come with me,” she said.

All his life, Bangura remembered the long hot walks his mom would take with him as a child strapped to her back in search of a spring or river far from the city. It was the reason he knew he wanted to take LifeStraws to Sierra Leone.

On the tour in March, his mom walked him down to a swamp, a stagnant waterbed about a mile away from the village.

“I said, ‘This water is not very clean,’” Bangura said. “She said, ‘I know, but this is the only way we get water.’

“It’s another heartbreaking thing to see, but it’s just the reality.”

On his trip, supported by individual donors as well as the Dennis and Phyllis Washington Foundation and Axiom of Missoula, Bangura delivered six LifeStraws, each with the capacity to support a village.

He handed the first one to a woman named Neyata, a mother whose source of drinking water for herself and her baby was murky white and filled with particles. She was a relative in Kambia, outside Freetown.

“It’s heartbreaking to know people drink that water, and it’s the only way they survive,” he said.

One of Bangura’s objectives during his stay of a month and couple of days in Sierra Leone was to conduct a needs assessment in villages, with questions about sanitation, water, roads and transportation, education and electricity.

Now that he’s back in the U.S., Bangura and the professionals working with him to launch the nonprofit will evaluate the assessments and make a plan to help based on the needs.

Already, Bangura has seen that solar panels would be a major contribution. He said Sierra Leone lacks major infrastructure, including electricity.

“The children want to study at night, but they don’t have lights,” he said.

Bangura’s return to Sierra Leone will depend on money. His mom would like to visit him in Montana as well, and he would like her to do so.

Seeing her was bittersweet, he said. He was happy to know she was alive, but also disappointed to see the poverty in which she had to live.

On his trip, he visited the metal shack where he grew up, a structure just 10 feet by 15 feet, and he returned to the orphanage that took him in, a place that’s still in operation. He recognized some of the teens there as ones who were children when he was a child, and they quizzed him on America.

“Have you been to New York?”

“Have you been to L.A.?”

“I said, ‘I’m from Montana.’”