American folk art show opens at Crystal Bridges Museum

BENTONVILLE, Ark. – Since its debut five years ago, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art has showcased works by well-known American artists like Georgia O’Keeffe and Andy Warhol. Now the Arkansas museum founded by a Wal-Mart heiress is turning its attention to ordinary objects made by unsung craftsmen, quilters and painters.

The new show, “American Made: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum,” features a collection that includes weathervanes, shop signs and spinning toys called whirligigs. The show opened during the Independence Day weekend and remains on view through Sept. 19.

The exhibition draws from the collection of the American Folk Art Museum in New York, billed by a curator there as America’s “alternative art history.”

While an occasional folk art piece may have been included in previous special exhibits, the new show is the museum’s first dedicated entirely to the genre.

“These are truly their treasures which they entrusted us with,” said Mindy Besaw, Crystal Bridges’ curator. “What you will get to see is the best of their collection.”

Items range from 4-inch paper figurines depicting horses and soldiers in the post-Revolutionary War era to an 8-foot, hollow copper weathervane featuring a Delaware Indian leader named Tammany.

“There are a few icons in the collection that I wanted to be on the checklist – pieces that haven’t traveled or haven’t traveled in a very long time: the Tammany weathervane, the man on a bicycle trade sign, pieces that are monumental in scale, or are so unique that you want them to be a part of the show,” said Stacy Hollander, chief curator and director of exhibitions at the American Folk Art Museum.

Though many of the objects are decorative or aesthetically appealing, their original purpose was mostly functional: decoys to attract ducks, amusements for children or advertising from a period when images were needed because literacy rates were lower.

“A weathervane is a practical form or sculpture, but it has to work. If it doesn’t work, it is not successful,” Hollander said. For its size, “it is surprisingly light.”

The decoys, on the other hand, are just as functional if they aren’t painted, she said.

“They just need to appear fowl-like to other birds,” Hollander said. “The silhouette is significant. The painted embellishment, that is an individual’s creativity coming into play.”

Crystal Bridges opened in 2011, founded by Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton as a showcase for American masters. The museum is located in Bentonville, the same town as Wal-Mart corporate headquarters. Regular admission to the museum is free, with the cost covered by Wal-Mart, but there is a $10 charge to see “American Made.”

Hollander said big-name artists featured elsewhere in the museum typically looked abroad for their influences: “These are artists who were working in a developing academic mode who were conscious of art that was being made in Europe and were aspiring to that kind of recognition for American art.”

In contrast, the creators of works in this show demonstrate the “American character in a way that isn’t influenced by European standards,” she said. “This is, in a way, America’s alternative art history, the art history that you don’t read about in textbooks. This is artwork that is first-hand testimony by Americans as they were becoming Americans.”

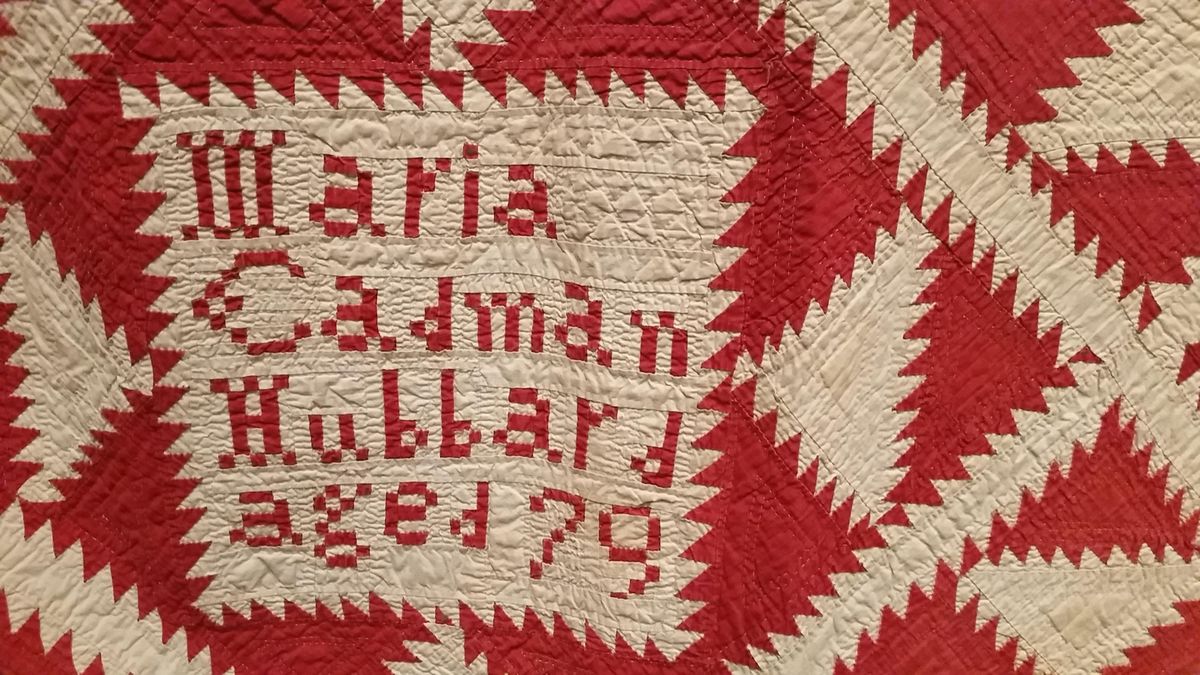

A patriotic-themed quilt, along with an Uncle Sam whirligig, greet visitors to “American Made.” Quilts adorn several galleries, including one from the 18th century that features the name of the quilter – Maria Cadman Hubbard – as boldly as admonitions that include “Forgive as you hope to be forgiven.”

“In a society where women held few legal rights, her name is a declaration, displayed within the household where she presided,” the gallery organizers note.

But some items are attributed to “Artist unidentified.” The anonymity is ironic: The creators are unknown, but the works were preserved for centuries because they were so good.

“What survives and gets recognized are the examples by those who are most-talented and have honed their skills to the highest level,” said Hollander. Those are the pieces that are “cherished … through generations, and they’ve survived for that reason.”