From pets to people? UC Davis vets’ stem cell work gives humans hope

DAVIS, Calif. – Morris has no teeth, the result of a drastic cure for a painful, chronic condition that makes the 8-year-old cat’s mouth sore and painfully inflamed. It’s a debilitating illness that has baffled pet owners and veterinarians alike for decades.

“We’re talking about a mouth that is inflamed with ulcers and looks like hamburger meat. It’s completely red and severely inflamed. It’s a very devastating disease in cats,” said Dr. Boaz Arzi, a dental surgeon and researcher with the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

In a clinical trial underway by Arzi and his vet school colleagues, Morris and about 20 other cats are getting stem cell therapy that is showing promising results.

Beyond being just a cure for cats, the stem cell treatment also holds tantalizing hope for humans afflicted with a painfully similar oral disease.

Stem cells and their regenerative abilities have long intrigued veterinarians and university researchers, who have identified their usefulness in everything from healing wounds in bluebottle dolphins to easing arthritis in pigs and horses. In recent years, there’s been added focus on clinical trials of stem cell therapies for companion animals, with the potential to become “translatable” treatments for humans. Because companion animals often live in the same environments, eat similar foods and can develop some of the same naturally occurring diseases as humans, the theory is that they make better candidates than lab mice or rodents in developing cures or treating disease.

Like the feline study at UC Davis, numerous stem-cell research projects are underway at veterinary schools across the country. At Tufts University, veterinary researchers’ treatment for dogs with rump lesions could help humans with Crohn’s disease. At Colorado State University, they’ve looked at stem cells to treat chronic hepatitis in dogs and chronic kidney disease in cats. In addition, private companies make stem cell products available for veterinarians to use in treating dogs, cats and horses.

“It’s a wave that’s crashing over us, and we have to figure out how to test, adopt and safely introduce this into medicine,” said Mark Weiss, a professor specializing in stem cell biotechnology at the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University. When it comes to stem cell therapies, he said, “we need to understand how to maximize their efficacy and completely understand their safety profile.”

Last summer, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued guidelines that require FDA approval for stem cell products manufactured for use by veterinarians. Academic researchers engaged in clinical trials, like those at UC Davis, however, can apply for exemptions from FDA approval.

“Most stem cell products are drugs,” FDA spokeswoman Juli Putnam said in an email. “As with any type of drug product, there are both risks and potential benefits,” including concerns about disease transmission, immune reactions, tumor formation, toxic contaminants and other outcomes.

For patients such as Debbie Nicholau, 62, the stem cell therapies being tested on Morris and other felines are a chance to grab relief from a similarly wrenching mouth disease. Nicholau, a retired nurse, developed several auto-immune illnesses in her 30s, but her most challenging condition cropped up three years ago when she was diagnosed with oral lichen planus, which makes eating and sometimes even speaking difficult.

“It’s like peppers on a raw wound. That’s what it feels like,” said Nicholau, who said she gets blood blisters inside her mouth and ulcers on her tongue and lips. She often wakes up with blood on her pillow from the sores. “My mouth is just raw and on fire most of the time. It’s not pleasant.”

And it’s also not cheap to treat. Nicholau uses a $300-a-tube gel for inside and outside her mouth. Until her insurance stopped covering the treatment, she was receiving twice-a-month IV infusions of immunity-boosting gamma globulins that cost roughly $6,700. Instead, she now takes steroids to ease her mouth’s chronic inflammation and pain, but battles the side effects: sleeplessness, weight gain, anxiety and mood swings.

There is no cure or known cause for oral lichen planus. According to the Mayo Clinic, it often strikes middle-age women and may be hereditary or related to a compromised immune system.

It’s rare, affecting less than 1 percent of the population, according to Dr. Nasim Fazel, a UC Davis Health System dermatologist and dentist, who specializes in oral mucosal diseases, such as the inflammation affecting Nicholau.

In many cases, “it’s chronic, difficult to treat and very debilitating,” said Fazel, who treats about 30 patients, including Nicholau. Not only does it “diminish a patient’s quality of life,” it also puts patients at greater risk of oral cancer.

Fazel is working closely with Arzi’s stem cell project to see if there’s potential for similar treatment in humans. “It’s so important,” Fazel said. “These patients, we don’t have a lot to offer them for treatment. Patients are suffering so badly; there’s a need for something that might work.”

At UC Davis, during a recent checkup following two stem cell infusions at the veterinary hospital, Morris appeared completely uninterested in his role as a possible medical pioneer for humans.

He hunkered down in the back of his “pet taxi” carrier, unwilling to budge. He only responded after some gentle coaxing by Megan Badgley, a UC Davis veterinary technician who oversees care for cats enrolled in the stem cell study. Badgley said Morris and the other cats are typically nervous when they’re being seen because for so many years they’ve lived in pain and endured numerous visits to veterinarians’ offices and vet hospitals seeking treatment. “We go as slow as they need us to go. They tell us when they’re ready,” she said.

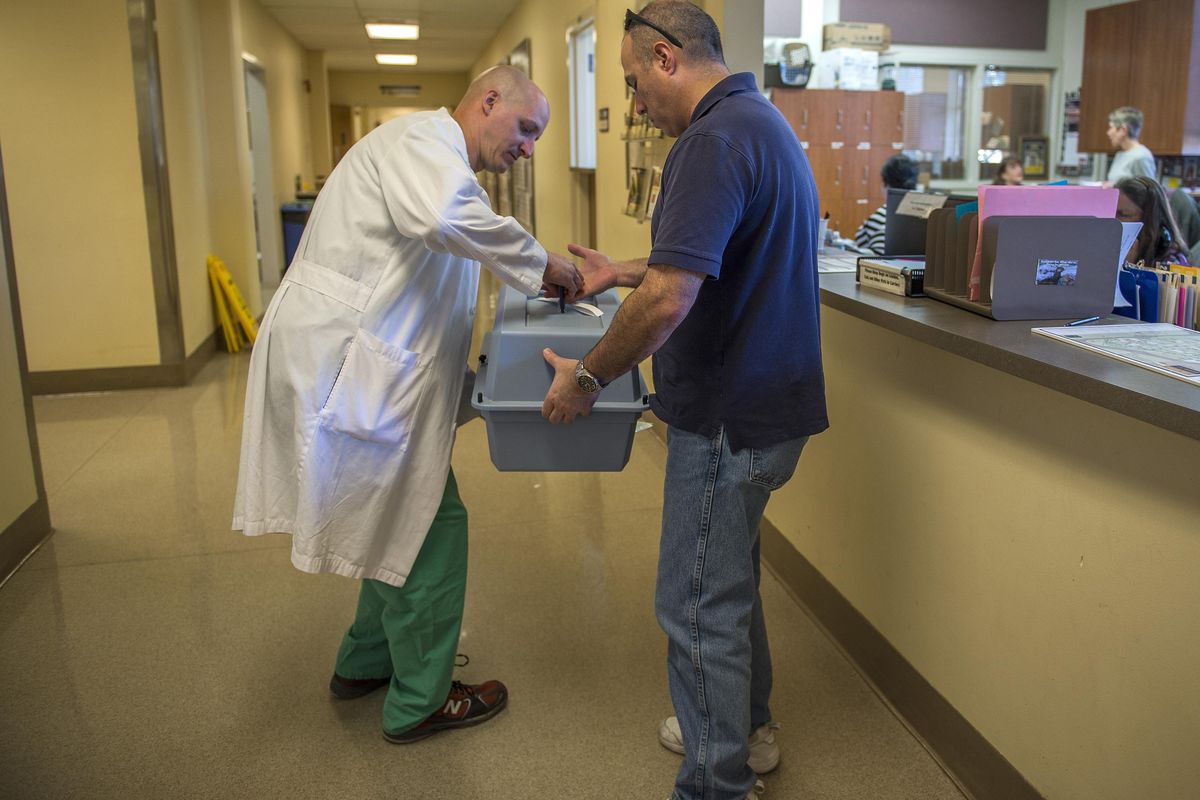

Adopted as a stray by Michael Altamirano, Morris’ irritated-mouth problems started appearing about three years ago. The caramel-colored tabby wasn’t eating well, was clearly in pain and couldn’t fully open his mouth to yawn, said Altamirano. He took Morris to several vets, including a specialist who extracted all of his teeth, the standard treatment for feline chronic gingivostomatitis, known as FCGS.

“Leaving in his teeth wasn’t an option,” said Altamirano, who estimates he’s spent nearly $3,000 on Morris’ disease care. Although his symptoms improved after going toothless, Morris wasn’t completely cured.

That’s exactly the feline patient the UC Davis vet school was seeking for its clinical trial, now in its third year. Morris is one of 20 cats – coming from as far away as Arizona to be treated – that suffer from FCGS but have not responded to teeth extractions.

And that’s where stem cell therapy has so far shown promise. Stem cells are extracted from feline fatty stomach tissue, purified and grown in a UC Davis lab, then infused by IV injection into a cat’s leg vein. Some cats get their own stem cells; others receive them from healthy felines. Most get two infusions, 30 to 45 minutes long, a month apart.

The treatment is intended to jump-start the cats’ immune system. Speaking in layman’s terms, “stem cells release chemicals or proteins that tell the immune system to behave properly,” said Arzi. “We convince the cells responsible for clearing inflammation to go back to doing what they’re supposed to be doing. Some are simply exhausted, so we revive them.”

In most cases, the severe oral inflammations have calmed down, if not disappeared altogether in afflicted cats.

“The majority have shown clear or substantial clinical improvement,” said Arzi. “From a scientific viewpoint, they’re a normal cat.”

Whether the treatment would yield similar results with humans remains to be seen. Genetic background, drug metabolism and other factors mean humans could respond differently than dogs or cats to a specific stem cell therapy.

For patients suffering from the disease, a clinical trial for humans can’t come soon enough.

Nicholau said she’d sign up “at the drop of a hat” in hopes of finding a cure. “This illness is so difficult to live with and to treat that people who have it are willing to do whatever we can to get relief. I’m willing to be a guinea pig.”