‘Thunder Boy Jr.’: Sherman Alexie aims for the kiddos with his new picture book

On the Spokane Indian Reservation where he was born and raised, Sherman Alexie is called Junior. Still.

He was named after his father, Sherman Alexie Sr., who died in 2003. There’s pressure to being a “junior” – one that Alexie didn’t really recognize until he got older.

“There’s a gravestone on the rez with my name on it,” he said by phone from Seattle earlier this month, “which is pretty damn intense. I would like there not to be a tombstone with my name on it until I’m dead.”

It wasn’t until high school, when he moved from the reservation school to Reardan High School, that he became known as Sherman. “I think I took over the name,” he said. “I had so not been Sherman on the rez that the geographic move, the cultural move to Reardan made me become somebody different.”

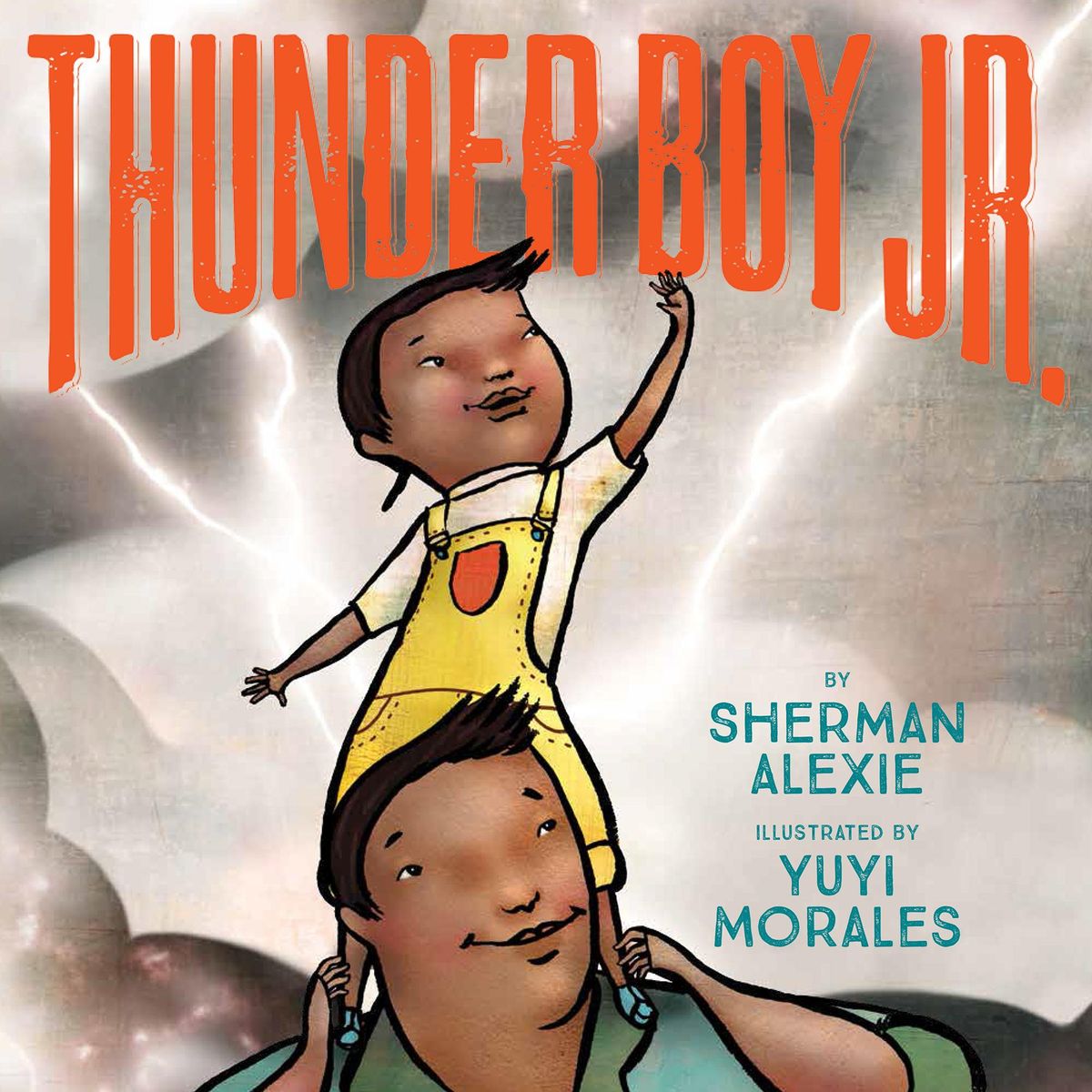

He explores questions of names and naming traditions in “Thunder Boy Jr.,” his latest book, and the first he’s ever written for young children. Geared for ages 3 to 6, it tells the story of a boy named after his father, Thunder Boy Smith Sr., and how the boy longs to for a name all his own. Illustrated by Yuyi Morales, the vivid and entertaining story delves into the child’s imagination and dreams, his love of family and desire to be his own person.

Of his father, Thunder Boy Jr. says, “People call him Big Thunder. That nickname is a storm filling up the sky. People call me Little Thunder. That nickname makes me sound like a burp or a fart.”

The success of his 2007 young adult novel, “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” which won the National Book Award, helped pave the way for “Thunder Boy Jr.,” he said.

“I loved how teens responded to ‘True Diary,’ so I kept thinking, ‘I want to go younger,’ ” he said. He also remembered the books his own sons loved, the picture books Alexie and his wife, Diane, had to read 1,000 times. He wanted to write a book that some young kid somewhere would come to love as much.

“I want some parent to be forced to read this book 1,000 times over the next three years,” he said, chuckling. He then launched from memory into lines from “The Adventures of Taxi Dog,” the book his sons adored about a decade ago.

“My name is Maxi, I ride in a taxi, around New York City all day, I sit next to Jim, I belong to him, but it wasn’t always this way …”

It only looks easy

Millions of parents have likely opened up a children’s book and thought, I can do that. Maybe some can, but it’s harder than it looks.

“I write poems so I thought it would be easier, because it is like writing poems. But it wasn’t. It was tough,” Alexie said. “I mean you’re writing for the kid, mostly, but you’re also writing for the adult who will read to the kid. You’re trying to write a book that’s going to appeal generationally. And that mix is difficult.”

The added challenge? That he was going for something bigger, more important than silly rhymes.

“I wanted to write a fun book that also had deeper socio-political meaning,” he added. “I’m not opposed to fun picture books. I’ll probably write one in the future. I wanted this one to do other things as well.”

Giving a name is an ancient but still vital tribal tradition. Alexie wanted to make it contemporary.

“The idea of a new name is amazing for the kids, because they do that anyway,” he said. “To see it validated, that feeling that ‘I want a new name, I want a new identity, I want to try something on,’ they’re way into that.”

Alexie added, “Naming might be destiny, but you change your name, and therefore change your destiny.”

He never thought about making one of his own sons a Sherman III. “I didn’t want to burden them with the name Sherman. But also, it’s a possessive thing to do. And it’s archaic. And it sets your child up in strange ways. So no, I was never going to name them after me.”

Story comes to life

After he’d written the text and it came time to hire an artist, Alexie said he told the publisher to show him work by “10 brown illustrators.” The samples he saw came from an ethnically diverse group. Yuyi Morales’ work “immediately popped out at me,” he said. “She captured boy energy and indigenous imagery in such a way in her own work that I knew she’d be perfect.”

Her list of published works is long: She illustrated the award-winning 2003 picture book “Harvesting Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez,” and has written and illustrated “Nino Wrestles the World” and “Viva Frida.”

The Mexican artist, who was born in Veracruz and who has lived in the United States since 1994, deftly blended cultural traditions in her bold, colorful pictures for Alexie’s book.

When Alexie saw the finished pictures, “I cried, because it was perfect,” he said. “And she was very careful, very interesting. She’s Mexican and Mexican-American. She brought in some Mexican indigenous imagery, some Southwestern imagery, Northwest imagery. …

“We wanted this kid and this book to have all those subtle, multi-indigenous images.”

What’s next

In the story, Alexie pays tribute to his mother, Lillian Agnes Alexie, who died last summer after a short illness. The female characters in the story are “Lillian” and “Agnes.” Little Thunder says “Those are fancy names. But they are normal names.”

“I’ve written a lot about my dad, but not much about my mom, and especially in the immediate aftermath of her death I wanted to remember her that way,” he said.

He was writing a lot of poetry about his mother after she died, and some of that will be included in a memoir, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” due out in the fall of 2017. He’s also continuing work on the sequel to “True Diary.”

In the meantime, he’s heading out on a book tour. He’s starting on the East Coast, but will be in the Inland Northwest this summer, hitting Spokane; Moscow, Idaho; and a host of small Washington cities he has not visited before.

“I’m doing these small stores that I’ve not done, like in Walla Walla and Yakima,” he said. “It’s going to be really fun.”