‘Sweetie talk’: Unthinking endearment that’s meant to comfort instead can feel demeaning

The women who call me sweetie can make me feel tiny and tucked in, as if they’re about to lay a cool washcloth on my feverish head, or take me out for post break-up ice cream.

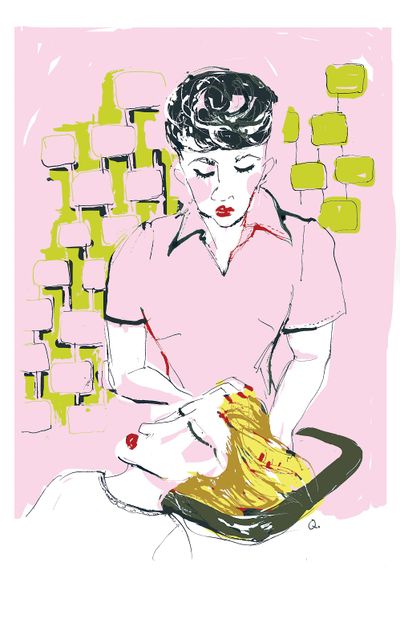

The women who call me honey bring me food in restaurants. These strangers who don’t know me give me forms to fill out and point, with lacquered fingernails, to places where I need to sign. They tell me my dog will be OK, that there’s a seat for me in the back, that they’ll take care of it.

The women who call me sweetie often render services. When they have more gray hair than I do, or wear their names on their shirts, or when I’m lonely, I don’t mind so much being called sweetie, baby, hon. It can feel like a wool blanket on a snowy night, the scratchiness mitigated by welcome warmth.

When I lived in the South, these women were older, bustier, heartier, and the names they called me had more color. When I lived in the South I was doll-baby, honey-child, sugar. When I lived in the South, I knew I had transgressed when they replied to a question with a question that wasn’t a question: “You aren’t from around here, are you, darlin’?”

But now, especially when a woman decades my junior says “Sit right here, my dear” before she cuts my hair, when a cashier at the grocery store hands me my receipt with a “Have a good day, hon,” I fear I will spoil both of our days by going all enraged New Yorker on her.

Why do I resist these unthinking endearments?

When my mother suffered from a terminal illness, I took her to doctor’s appointments, sat with her during dialysis, and stood like a Gorgon by her hospital bed. Most of her caretakers were kind, respectful. But when my mother, shrunken by cancer but still herself, still someone who had taught at an Ivy League university, published books, and made a living as an artist, was called sweetie or honey, these attendants became the locus of my silent, impotent rage.

I thanked them for their sympathy and hated them for their insensitivity. I wanted to scream that my mother was not a child, to educate them about how their language infantilized her, took away a gravitas she had spent years earning. Instead, I said nothing.

As a professor, I assume that students are doing the best they can and try not to blame them for things they haven’t yet learned. Perhaps no one has ever spoken to them about the power of naming, though the mean girls and the bullies know this intuitively. They demean weaker peers by refusing to call them by their proper names and claim dominion by conferring nicknames – an act of appropriation, of ownership.

When I taught at Airway Heights Corrections Center, a medium-security prison, I asked the inmates what they would like to be called, wanting to respect their wishes, reminding them that the first thing slave owners did to their captives was give them new names. An African-American prisoner corrected me: “That wasn’t the first thing they did.”

When women call me sweetie, honey, baby, dear, I find I am inadequate in the moment to do what I do in the classroom: instruct.

I try to think about what their lives might be like, these women. Perhaps they have kids at home and don’t get enough sleep, don’t make enough money, don’t have enough time and empathetic imagination to think about how these words could make someone feel. Perhaps they believe it’s a way of connecting, another form of rote friendliness, like telling me to have a nice day. Perhaps it’s a tic they’re unaware of, something they’ve picked up from their own mothers.

In the quick transaction when I’m asked to make sure my seatback is in its full, upright position, when I’m sitting with scissors near my head, or being shown to my table, I don’t want to be that irksome teacher who asks them to think about how they use language. I know many would find this nit-picking, an instance of what they might call “political correctness.” Someone who cares less than I do about how language reflects our values and biases may find the problem trivial, not worth thinking about.

But I do think about it and wonder about my own varied responses – from feeling cared for by some to wanting to strangle others.

In truth, I sometimes feel close to the women who call me sweetie, grateful for their kindness and attention. The intimacy conferred by these utterances – when not merely reflexive – makes me miss my mother, dead now seven years but far from absent, who never called me sweetie, honey, or baby, only Rach. These women make me long for the time when a soft word – even a shortened version of my name – could soothe.

Rachel Toor is a professor of creative writing at Eastern Washington University. She is the author of one novel and four books of nonfiction, the most recent of which is “Misunderstood: Why the Humble Rat May Be Your Best Pet Ever.” Her column, “Everything Is Copy,” will appear monthly in the Monday Today section.