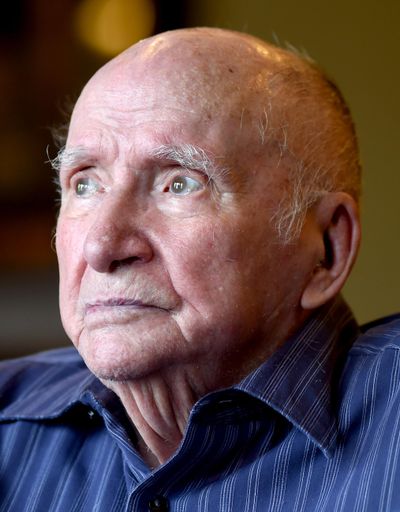

Bataan Death March survivor, Montana artist Ben Steele dies at 98

BILLINGS – Ben Steele’s hold on his sanity as a prisoner of war after surviving the Bataan Death March relied on hidden scraps of paper, stolen pieces of charcoal and his artist’s memory of scenes from his home in Montana.

“I used to dream about Montana more than anything else, more than I did food – and I used to dream about food all the time,” Steele once said.

“I was awful sick and I thought I was going crazy, so I had to do something to occupy my mind,” he said.

Steele, a former art professor, died Sunday in Billings with his wife Shirley and daughters Julie Jorgenson and Rosemarie Steele at his side.

He had been in hospice care for more than a year and succumbed to an infection, Julie Jorgenson said. He was 98.

Many people knew Steele’s stories from World War II and what he endured as a prisoner, but “it’s his personality, his warm caring personality that made people love him,” Jorgenson said. “His students would come up to me and say, `Ben and I have a special bond.’ But he made everyone feel special.”

During the war, other prisoners saw what he was doing and suggested he draw what he saw around him. He created depictions of life in the camp in charcoal on the floor, and then with pencils and paper that other prisoners smuggled to him.

“I kept little scraps of paper, the inside of cigarette packages, that kind of thing,” Steele said in a 2004 interview with the Billings Gazette. His original sketches were lost.

After his liberation in 1945 and during his long recovery, he re-created sketches and made paintings depicting the march and his 3 1/2 years as a prisoner of war in the Philippines and Japan.

He said the artwork helped him deal with the suffering he endured and the faces of the dead and dying he saw in his mind’s eye. Steele was bayoneted, starved and beaten and suffered dysentery, malaria, pneumonia and septicemia. He lost 80 pounds.

“I had lots of problems to work through,” he said in 2004, “and the doctors thought the art was a good idea.”

Steele became an art professor at Eastern Montana College, which later became Montana State University-Billings.

He said he learned to forgive his Japanese captors because of his relationship with Harry Koyama, an art student of Japanese heritage who took courses from him.

“He’s been a part of my life since I met him in college in the 1960s,” Koyama, a western artist with a gallery in Billings, said about Steele. “That’s even more of a humbling experience to know that I had not just an effect, but a positive effect on his life.”

Steele was born on Nov. 17, 1917, in the small Montana town of Roundup and grew up riding horses, roping cattle and occasionally delivering supplies to western artist Will James.

He was a U.S. Army Air Corps private in the Philippines when the Japanese captured his unit in 1942 during World War II. Thousands of soldiers died during the 66-mile march under a scorching tropical sun.

Steele’s survival story was chronicled in the 2009 New York Times best-seller “Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath,” by Michael and Elizabeth Norman.

An Ohio teenager, Lexi Winkelfoos, traveled to Montana twice to visit Steele after reading the book for a history project when she was a sophomore.

“I just wanted to know that he was happy after everything he had been through,” Winkelfoos said during her second visit last year.

Steele continued to paint into his late 90s.

“Many times he would draw the same image over and over as if exorcising it from his conscience,” Brandon Reintjes, curator at the Montana Museum of Art and Culture at the University of Montana told the Gazette last year. “He has a nearly photographic memory and these events are indelibly embedded in his mind.”

His powerful sketches and paintings of his time in captivity are housed at the university museum in Missoula.

“I kind of felt an obligation to the guys who went through that, to illustrate what went on over there,” Steele said. “I wanted to tell the story.”

A memorial service is scheduled at 1:30 p.m. Oct. 4 at Montana Pavilion at MetraPark.