This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Are we Cancer Town USA? It depends, as statistics paint complex, incomplete picture of disease

Is this Cancer Town USA?

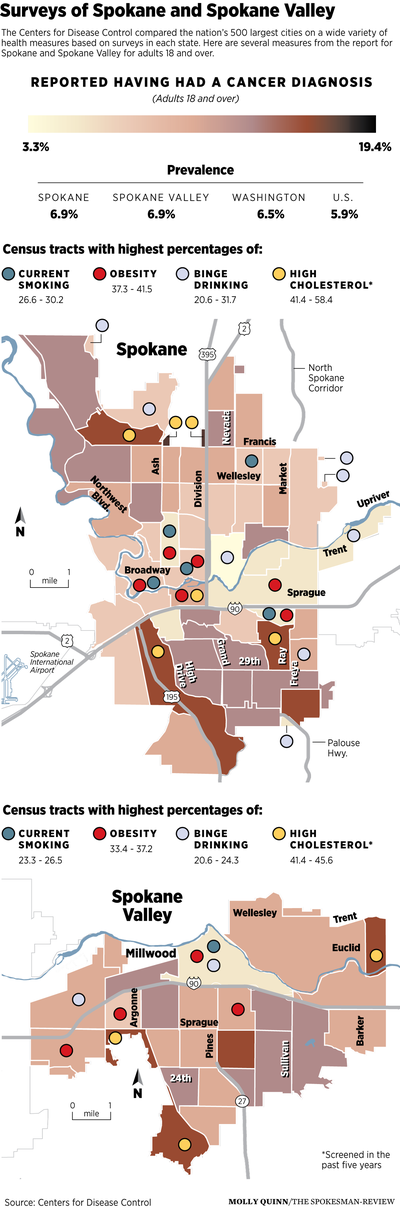

A new federal project comparing health outcomes in the nation’s 500 largest cities makes it seem so. Spokane and Spokane Valley are tied for the nation’s highest rate of cancer diagnoses among adults – not including skin cancers – at 6.9 percent, according to the project by the Centers for Disease Control.

That figure, based on a self-reported annual survey, is a percentage point higher than the national average. It reflects the number of people here who say they’ve ever been given a cancer diagnosis.

But other statistics complicate that picture. Spokane County’s “incidence rate” of new cancer cases is above the national average but below the state average. Washington overall ranks 22nd for the average number of new cancer diagnoses per 100,000 people.

When you’re asking questions about cancer – whether it’s an individual case or a broader measure – a lot of times the answer is: It depends.

“You’re certainly not on our radar screen as ‘Cancer Town USA,’ ” said Patti Migliore Santiago, program manager of the Washington State Cancer Registry.

County health officials agree: We have our share of cancer here – and more than our share of breast, lung and skin cancer – but there’s reason to be wary of any single statistic that puts us at the top of a national list.

In an average year, more than 2,600 new cases of cancer will be diagnosed in Spokane County, and 924 people will die from cancers, according to state figures.

Spokane has slightly higher rates of breast cancer and lung cancer than the national average, and higher rates of skin cancers, too. But health officials note that there is great variety in reporting on the types of skin cancers state to state.

Both Spokane and Washington state show lower rates of prostate cancer.

Generally speaking, the main types and incidence rates of cancers are fairly consistent across the country, said Shelley Berdar, the oncology program manager for Providence Sacred Heart and Holy Family hospitals.

However, public health officials agree that whatever figure you focus on, cancer rates could be lower. More people smoke and binge-drink here than the national average, according to the CDC. A lot of people underestimate sun safety measures that can lead to deadly melanomas, officials say. And too many people fail to take advantage of early cancer screenings such as colonoscopies or CT lung scans, while our high poverty rate means that many residents have limited access to such services.

Dr. Robert Gersh, a medical oncologist with Cancer Care Northwest and medical director of oncology at Providence, said a widespread lack of screenings and preventive measures is a “health system failure,” and that local health officials are trying to expand screenings with grant-funded programs and education. He said a “recurring theme” in his experience is the arrival of a patient – often a man who is averse to going to the doctor – who ignores warning signs and doesn’t get screened until showing up with a late-stage cancer.

“We know we can cut the (mortality) rate of colon cancer by 50 percent by implementing appropriate screening measures,” Gersh said. “I think that is really a need for our county.”

500 Cities

The new cancer-rate statistics are part of the CDC’s 500 Cities project, which provides detailed breakdowns on health measures for the country’s biggest cities. The project delineates a variety of health measures by census tract.

According to the project:

- more residents of Spokane and Spokane Valley are binge drinkers (18.5 percent and 19.6 percent) than the national average (16.8);

- more adults here smoke (19.6 percent in Spokane, 19 percent in Spokane Valley) than the national average (17.7);

- more of us are obese (32.6 percent in Spokane and 31.5 percent in Spokane Valley) than nationwide (28.7);

- and more residents of Spokane and Spokane Valley fail to get a good night’s rest, have lost all their teeth and reported “mental health not good” for extended periods.

The project also breaks down information by census tract, showing where certain behaviors and diagnoses are most prevalent: Higher rates of unhealthy behaviors, from smoking to binge drinking, and lower rates of insurance and access to health care all show up in lower-income neighborhoods, as do higher rates of health problems.

The project reinforces what local public health officials have been saying for years: People who live in Spokane’s poorer neighborhoods experience income inequality in a very direct, unambiguous way – through shorter lives.

These differences result in a gap in life expectancies that is shocking: An 18-year difference in expected life between someone living in Spokane’s unhealthiest neighborhood (downtown) and its healthiest (Southgate). The Spokane Regional Health District measured this problem in 2012, with a report titled “Odds Against Tomorrow.”

A more recent comparison provided by the district showed age-adjusted mortality rates by neighborhood: Every year, more than twice as many people die per 100,000 residents in East Central, Nevada/Lidgerwood, Emerson/Garfield, Logan, West Central and Hillyard neighborhoods than in Manito, Rockwood or Southgate neighborhoods.

“It’s fascinating because the geographic distances between some of these neighborhoods at the extremes are so small,” said Stacy Wenzl, data program manager for the district.

Screenings affect figures

One of the dichotomies shown in the CDC 500 Cities report is that the neighborhoods with the highest rates of unhealthy behaviors are not necessarily those with the highest rates of cancer.

For example, one of the census tracts with the highest cancer rates is the area of South Hill along High Drive. It also has among the lower rates for smoking, binge drinking and other risk factors.

Santiago, the head of the state cancer registry, said that’s one of the ways in which cancer statistics can be limited. Sometimes they show that a population has greater access to screening and medical care and therefore are diagnosed more quickly and frequently.

“The numbers reflect who has access” to care, she said.

Berdar, the Providence oncology program manager, said you can see the influence of increased screenings in breast cancer statistics. Breast cancer is by far the most commonly diagnosed and treated type of cancer in Spokane County and Washington state – though it is second to prostate cancer nationally.

Part of the reason for that is that there has been a long-standing and effective public campaign to encourage mammograms, which means more cancers are caught and treated, Berdar said. Officials said that women are, generally speaking, more likely to get regular screenings for breast cancer than men are for any type of cancer.

“The screening is much higher in breast cancer than it is in other cancers,” she said.

Santiago oversees a project that compiles detailed data on cancer across the state. Her department runs the annual Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, a survey conducted in every state. That survey is what’s used to come up with the cancer rates in the 500 Cities survey – the one that showed 6.9 percent of Spokane and Spokane Valley adults had a cancer diagnosis in their lives.

She’s wary of taking the survey too literally on cancer rates.

“It’s self-reported, and it’s on the telephone, so it’s based on people who will stay on the phone and do the survey, or who even have a telephone,” she said.

Her office gathers detailed statistics on diagnosed cancer cases and is preparing updated figures for release this week. They show that Spokane County’s overall cancer incidence rate is 494.8 new cases each year per 100,000 residents, based on the years 2012-14. Statewide, the incidence rate is 507.9. The national rate is 454.8

Spokane County’s death rate from cancer, meanwhile, is actually higher than the state average – 169.2 in the county versus 158.4 statewide.

Officials said it’s often difficult to tease out why there might be such differences in the data. Places with higher incidence rates than death rates may reflect populations where people generally have greater access to care, and get earlier treatment, but it’s impossible to say for certain what leads to such a difference in statistics.

Gersh, the Cancer Care Northwest oncologist, said he believes that most cancers in our region stem from the same set of causes as cancers anywhere, and are not directly a result of environmental factors.

He said a particular concern now is the need to have more young people vaccinated against human papillomavirus, or HPV, which can lead to a variety of cancers later in life. He noted that the county’s overall vaccination rate is low, and that convincing people to get this relatively new vaccination is not always easy.

Among the cancers HPV causes are oral cancers, Gersh said – the kind that can sneak up on people with little warning. He said he’s seeing more cases of advanced oropharyngeal cancer among a certain profile of patients: white men in their 50s, not smokers or drinkers, generally healthy, who find a lump in their neck.

“It’s kind of a silent epidemic,” he said.