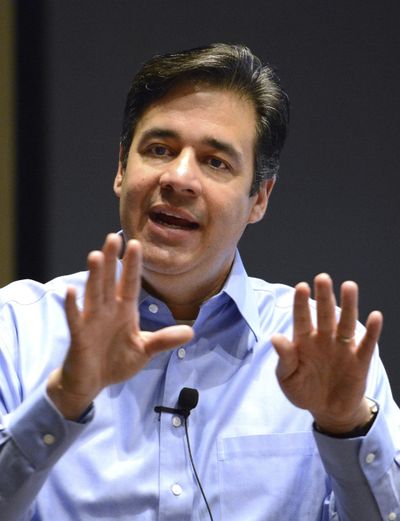

Following town hall backlash, Labrador says health care comment ‘wasn’t very elegant’

Idaho Rep. Raul Labrador drew intense criticism over the weekend for suggesting at a town hall meeting in Lewiston on Friday that “nobody dies because they don’t have access to health care.”

In response, the Republican congressman said Saturday night that the comment “wasn’t very elegant” and was taken out of context.

“I was responding to a false notion that the Republican health care plan will cause people to die in the streets, which I completely reject,” Labrador said in a statement to the Statesman, which was also posted on his Facebook page.

Labrador said he had a lengthy exchange with the constituent “in which (he) explained to her that Obamacare has failed the vast majority of Americans.”

He said the media is focusing on “a five-second clip” in which he responded to the woman’s claims that he’s “mandating people on Medicaid accept dying” by saying: “That line is so indefensible. Nobody dies because they don’t have access to health care.”

Prior to his Saturday night clarification, some on social media speculated that Labrador was referring to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, a 1986 federal law that requires emergency departments to stabilize and treat anyone who comes into their facility, regardless of insurance status or ability to pay.

The congressman said that’s exactly what his statement meant.

“I was trying to explain that all hospitals are required by law to treat patients in need of emergency care regardless of their ability to pay and that the Republican plan does not change that,” he said in his release.

Labrador said he held four town halls “to have an honest and frank discussion with my constituents about important issues.”

“It certainly doesn’t help that the media is only highlighting a five-second video, instead of the entire exchange,” he wrote, offering a link to a video of his discussion with the constituent.

In the video, the woman asks Labrador “to explain to taxpayers in this room how we are going to pay for the $20 million in increased indigent care costs when we cut $800 billion out of Medicaid” with the House vote on Thursday to approve the American Health Care Act.

“Everybody on Medicaid in Idaho, which is 18 percent of our population – not to mention the 83,000 Idahoans that need federal assistance to bargain and purchase their private health insurance – are still going to get sick,” said the woman, who later identified herself as an emergency room nurse.

“And when they get sick, they’re going to get sicker, because they won’t have primary care, they won’t have preventative care, and they’re going to lose their jobs, they’re going to lose their homes. And they’re going to have a $10,000 ICU stay for what could have been a $35 primary care visit, $5 worth of penicillin for their antibiotics,” she said before being met with applause.

In response, Labrador told the constituent that Oregon was an example of a state that had increased Medicaid spending on indigent care to find that “most of the poor people ended up going to the ERs anyway.”

Several Idaho health care providers responded to Labrador’s comment, including a former chief medical officer at Saint Alphonsus in Boise. While Labrador’s Saturday statement clarified that his comment referred to the availability of emergency care, Idaho doctors seem to agree that’s simply not enough.

“While it’s true that people can, for example, go to the emergency room and get care regardless of their ability to pay, that’s hardly a solution for treating patients with preventable disease over the long term,” Boise doctor Richard Radnovich told the Statesman.