Charles Manson, cult leader and serial killer who terrified nation, dies at 83

Charles Manson, the fiery-eyed cult master whose lemming-like followers staged a bloody two-night murder rampage in Los Angeles in 1969 that gripped the city with fear and shocked the nation, died on Sunday at a hospital in Kern County, California. He was 83.

A spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation confirmed the death by email, saying he died of natural causes. Manson, who was serving a life sentence at California State Prison in Corcoran, California, had had health problems in recent years and was hospitalized in January for gastrointestinal bleeding, according to news reports.

The sheer incomprehensibility of the acts – mutilation and ritual stabbings of seven victims, among them rising Hollywood starlet Sharon Tate, then eight months pregnant by her movie director husband, Roman Polanski – left the public aghast and police investigators stumped for months.

For many, Manson and his ragtag entourage of runaways, two-bit criminals and blindly loyal worshipers also symbolized the dark, even contradictory, excesses of the drug-driven, free-love ’60s, especially in California.

There, Manson and his so-called “family” members wandered the countryside, scavenging, stealing and preparing for an apocalyptic race war prophesied by their leader and dubbed “Helter Skelter” after the Beatles song.

A prelude to the conflagration was the slaughter of the seven victims in two affluent Los Angeles neighborhoods. Orchestrated by Manson on two successive nights in August 1969, the seemingly random killings were calculated to hasten the race war by making them appear committed by black militants. That in turn, he told his followers, would stir white sentiment against blacks, triggering widespread violence by blacks.

The scheme bore surface plausibility with the rash of urban explosions throughout the 1960s, culminating in the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and nationwide rioting.

Investigators, however, said the attacks also appeared motivated, at least in part, by Manson’s uncontrolled rage in the weeks leading up to the murders, when Hollywood agents rejected his self-proclaimed musical talents.

The slayings – known collectively as the Tate-LaBianca murders – led to the arrest and conviction of Manson and four of his followers in 1971. All were sentenced to death in the California gas chamber, but the sentences were reduced to life in 1972 when the state Supreme Court abolished the death penalty.

Over the years, the Helter Skelter massacres, as they were often described, attained macabre folklore dimensions, generating books, songs, movies and even an opera.

Manson transfixed the nation with his roving, luminous eyes and courtroom theatrics during the months-long trial in which he and three female followers – Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten – were convicted. A fourth family member, Charles “Tex” Watson, was convicted in a separate trial.

Manson and the women, as well as family supporters outside the courtroom, repeatedly disrupted the proceedings with antics, shouting often unintelligible slogans and chanting protests in unison. Once, Manson was restrained by bailiffs when he lunged at the judge.

“Look at yourselves,” he shouted another time, glaring at the spectators. “You’re going to destruction.”

Vincent Bugliosi, the hard-charging deputy district attorney who prosecuted Manson, described the Manson name as “a metaphor for evil.”

Manson was a study in stark contrasts. Small and scrawny, he was also charismatic and held an almost hypnotic power over his followers, especially women. Some believed he was divine.

Investigators, academic researchers and journalists found him alternately erratic and focused, a proficient guitarist, a lover of animals, a racist and anti-Semite with a left-leaning hatred of the “establishment” and corporate America and bitterness over his rejection by the music celebrity world of Hollywood.

He was not crazy, but he could fake it and had an insatiable need to control others, prompting him to recruit naive and malleable acolytes to his family, according to behavioralists who studied his life.

“Basically, Manson was a coward,” Eric Hickey, dean of the California School of Forensic Studies at Alliant International University, told Maclean’s magazine in 2012. “He was the kind of guy who had other people do his bidding, and I think he really enjoyed taking advantage of people who were gullible.”

Charles Milles Manson was born on Nov. 12, 1934, in Cincinnati, the son of an unmarried 16-year-old girl who supported herself on petty crime.

He never knew his father, and with his mother periodically jailed, he was shunted among various relatives in small-town West Virginia and Kentucky. He began engaging in petty theft himself and ended up in a series of foster homes and reformatories.

His education stopped at the seventh grade. While only sketchily literate, he scored a high-normal IQ of 121 while in prison.

He married twice, first to a teenage waitress, Rosalie Willis, in 1955, divorcing in 1958. Then in 1959 he married a woman with a prostitution record named Leona “Candy” Stevens, according to prison records. That union also ended in divorce. A son from his first marriage, Charles Manson Jr., who renamed himself Jay White, committed suicide in 1993. He had a son from his second marriage, Charles Luther Manson. He may have other children.

Manson drifted to California in the mid-1960s, was drawn to the beads-and-hippie scene in San Francisco and later Los Angeles. He began gathering a loose following of devotees, many of them disillusioned and confused youngsters from across the socioeconomic spectrum.

He attempted to ingratiate himself with the Hollywood glitterati, using his guitar and songwriting as a wedge, and was briefly befriended by Beach Boys member Dennis Wilson, record producer Terry Melcher, son of actress Doris Day, and others. He managed to get one song on the Beach Boys’ album “20/20” in 1968. It was titled “Cease to Exist” but revised and retitled “Never Learn Not to Love” by Wilson. Little else came of his efforts, leaving him angry and bitter.

Meanwhile, his followers, ranging loosely from a handful to a few dozen, encamped at various sites, abiding by his strict rules of communal living, including mandatory group sex and drug use.

“We took hundreds of LSD trips together,” Krenwinkel said in a 1994 prison interview with Diane Sawyer of ABC News. Of group sex, she said, “It was always very planned because it was a means of control.”

Women were entirely subordinate to men. They turned over their money to Manson. “The women did the cooking … The men ate first and the women got what was left,” wrote Jeff Guinn, journalist and author of “Manson – The Life and Times of Charles Manson.”

Four children were born into the family, at least one fathered by Manson.

It was during this time in the late 1960s that his vision of racial Armageddon jelled as well, guided, he asserted, by biblical prophecy and coded language in the Beatles’ White Album in such songs as “Helter Skelter,” “Blackbird” and “Piggies.”

During the war, in which blacks would overcome whites, he preached, his followers would go underground with him in Death Valley, then rise again to take over leadership from the victorious blacks.

On the night of Aug. 9, 1969, the first of two family teams entered an affluent Los Angeles neighborhood, targeting a home formerly rented by Melcher. Manson knew Melcher had moved but picked the house assuming it would be tenanted by people similarly wealthy, influential and deserving of death.

The team forced its way in, repeatedly beating, stabbing and shooting Tate and three friends – coffee heiress Abigail Folger, her boyfriend Voytek Frykowski, and celebrity hairdresser Jay Sebring. A fourth victim, Steve Parent, an acquaintance of the property’s caretaker, was shot in his car outside the house. Polanski was abroad at the time.

Late the next night, Aug. 10, another family team drove to a second upscale neighborhood where Manson picked a house adjacent to one where he and friends had partied earlier that year. The group broke in and with ritual savagery killed Leno LaBianca, a grocery store chain operator, and his wife, Rosemary.

At both houses, the intruders smeared bloody slogans on walls and furnishings – “Death to Pigs,” “Rise” – as well as a telltale Black Panther paw print to mislead police.

Investigators were stymied for months. They got their break when Atkins, jailed in connection with an unrelated murder, confided to cellmates about the Tate-LaBianca slayings, and word reached officials. Fingerprint and ballistics evidence at the scene confirmed Atkins’ assertions. Manson, also in custody on unrelated charges, was quickly indicted.

Prosecutors depicted Manson as the meticulous mastermind of the murders, and while family members acknowledged his planning role, they said he did not participate in the killings. The jury nevertheless found him equally culpable under California’s joint-responsibility rule.

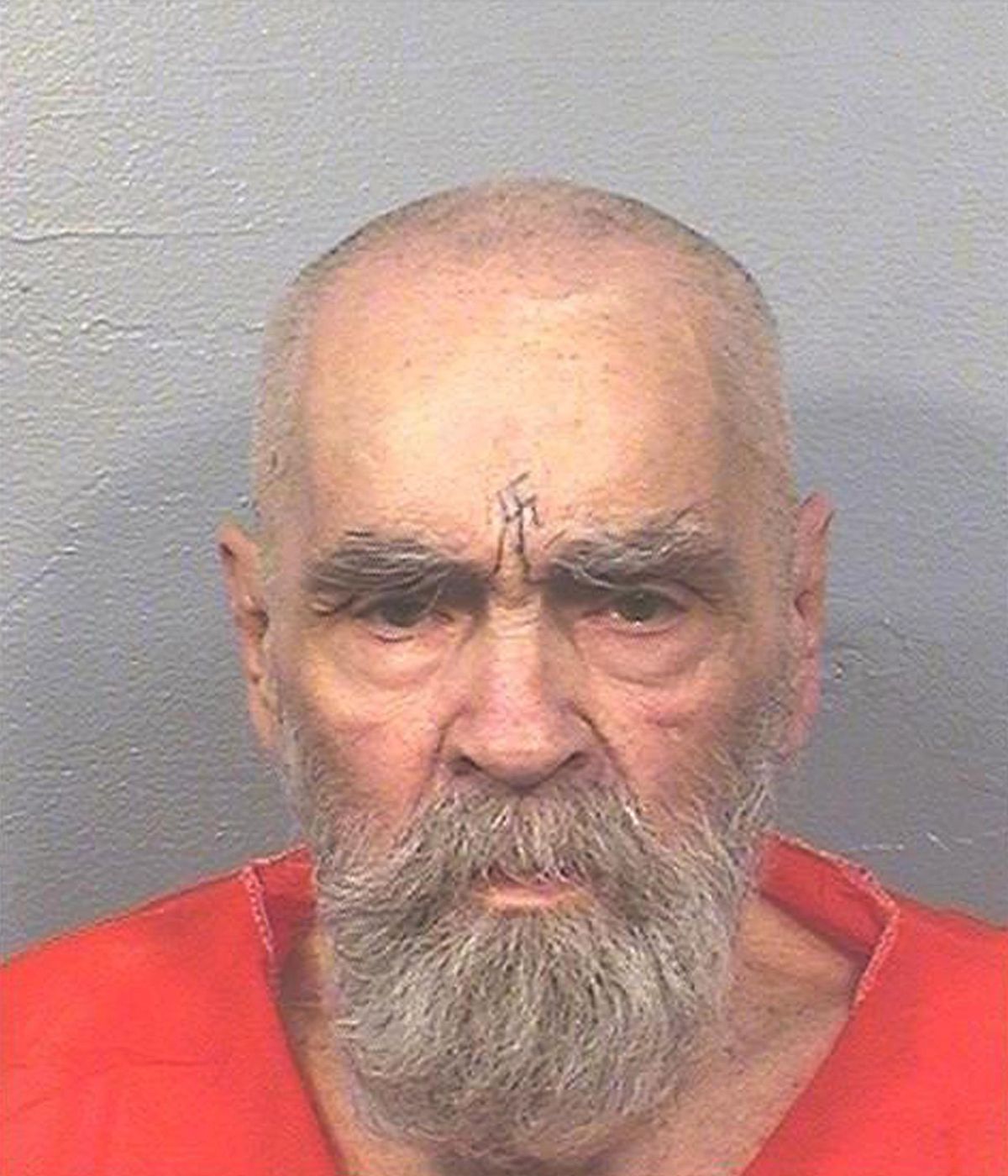

Manson spent his years behind bars answering mountains of mail, weaving scorpions and spiders from string and granting occasional TV interviews. As he aged, his eyes dulled, his scraggly hair and beard whitened and the swastika carved on his forehead began to fade.

Atkins died in prison in 2009 at 61.

Charlie Rose, in an Emmy Award-winning interview on the CBS “Nightwatch” news show in 1987, asked Manson for his reaction to the public perception of him as a “monster.”

His answer: “What you see is what you get.”