Summer Stories: Before You Blow

You’d met Joey at Geno’s Fabulous Pizza, where you waitressed the summer before your senior year at Shadle Park. He was a clowning, lanky sophomore at Gonzaga University who made the comically big lasagnas at Geno’s (“Noodle-sauce-cheese, noodle-sauce-cheese, lather-rinse-repeat,” he’d always say.) He sidled up on your second day. “Excuse me, Jeans. Can I get that ass’s phone number?”

OK then. So it was to be love.

Joey and his roommate Patrick were from Berkeley. For California Catholics, GU was a last-gasp safety school – get a minor-in-possession and a few D’s like Joey had, and your father exiled you to cold, sleepy Spokane, which he thought of as monastic because he’d seen students trudge through snow, hoods up on their heavy parkas.

Spokane was indeed cold, and its downtown sleepy, but Joey and Patrick were anything but monks. They got drunk every day, sometimes with the priests. They bought weed from an English prof. They talked their way out of DUIs.

They had so much fun they called Gonzaga Gonzo U. And the fun wasn’t confined to school. They treated the whole city like a college rental: no respect for windows, speed limits, property. To them, the word Spokane was a modifier that meant out-of-control, decadent fun.

They didn’t just get drunk, they got Spo drunk they broke into the neighbor’s garage and stole his tools. Joey was Spo hungover the next day he puked in the same neighbor’s flowerbed. Patrick was Spo horny he asked out the 23-year-old checker at Safeway, Harmony.

And that’s how you ended up late that summer in Harmony’s Ford Pinto, Patrick in the passenger seat, you and Joey smashed in the back seat on either side of Harmony’s kid Morton. Morton was maybe a year old, a pacifier bobbing in and out of his mouth.

“Morton?” you asked his mom. “Is that a family name?”

“It’s a kind of salt,” Harmony said.

You were drinking Schlitz Malt Liquor, cans with a big blue bull – Joey thought Schlitz was classier than regular beer.

“You should call him Sporton,” Joey said. “Like … Morton from Spokane.”

“I think that would limit his options,” Harmony said.

That night Harmony parked along Upriver Drive, near Boulder Beach. You all drank the beer and flirted around and someone – Patrick, maybe – suggested skinny-dipping. You were nervous, but it was three-to-one (Sporton abstaining because he’d fallen asleep in the back seat.)

You were nervous because you and Joey had done nothing to that point except kiss, make out a little after your river adventures. It was all you’d done with anyone. And now you and this college boy were about to get naked together.

Crazy thing, love.

Sometimes you just fall for someone. But sometimes you decide to love. You say, OK, this is the boy I’m going to love, the boy I’m going lose my virginity to – right here in this cold river.

And when you decide that, the boy can do anything. He says something inane, like, You should call him Sporton, and you don’t think, What am I doing with this idiot? You think, Oh, that is Spo funny. I should probably have sex with him.

Crazy thing, love.

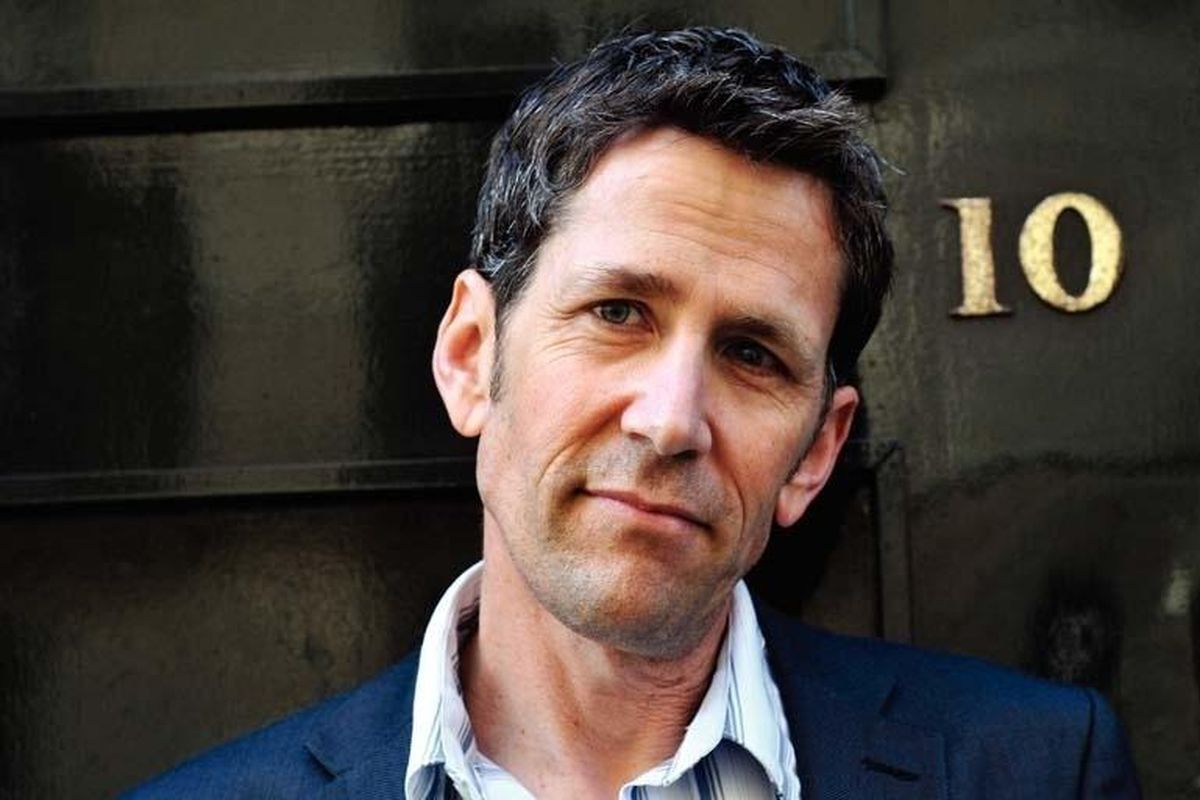

Joey McCune’s thick brown hair formed a shelf over his wry, cocktail-olive eyes and constant half-smile. Maybe it was you being in high school and him being in college – but every stupid thing he did and said that summer was comic gold.

“What do you say, Jeans?” he asked. “Swim naked with me?”

You looked down at his hand on your leg. “Sure,” you said. “Let’s do it.”

YOU THINK about this now, thirty-five years later, home in Spokane to visit your parents, sitting in traffic on Division Street, when you happen to glance over and see those green eyes settled in a bloated, balding face on a bus bench.

Joseph J. McCune is an attorney-at-law here in Spokane, a specialist in personal injury cases and DUIs and, apparently, getting clients from bus benches.

Coincidentally, you are also a lawyer, in San Diego, a corporate attorney who specializes in intellectual property rights. You don’t mean to condescend, but you’ve heard lawyers like Joseph McCune called “bottom feeders.” Joey’s particular contribution to juris prudence is the legal theory that one should never consent to a Breathalyzer. “CALL JOE BEFORE YOU BLOW!” the bench advises.

“Mom!” snaps your daughter, Meghan. “Would you go? The light changed … like two days ago!”

Coincidentally, Meghan is the age you were that very summer. And she is not happy being back in Spokane, visiting grandparents who keep staring at her septum ring like … well, like there’s a ring in their granddaughter’s septum.

For the last year, you and Meghan have battled over nose rings, curfews, and mostly, this hunk of idiocy named Kyle. When you suggest that perhaps Kyle might not raid the refrigerator every 20 minutes, or that he might want to write his own term paper, Meghan cries out in the song of her people: When are you going to start treating me like an adult?

“Mom! Go!” Horns are honking behind you.

But you can’t look away from the bus bench and Joey’s green eyes. “You know when you become an adult?” you ask your daughter.

“What?” Meghan is horrified, the way she is whenever you try to say something meaningful, or actually, whenever words come out of your mouth. “Seriously, Mom! Are you having a stroke?”

Finally, you look over at your 17-year-old daughter and say, “I think you become an adult the first time you see through love.” And then, with your daughter fuming and the light turning yellow, you drive away from Joey’s green eyes forever.

But you were having second thoughts. “It’s cold out here,” you said.

“We don’t have to go in the water,” Joey said. “We can just lie down somewhere.” You felt his hand on your waist then. Even at dusk, you could see those green eyes.

That’s when, in your peripheral vision, you saw something you couldn’t quite put together. The car was creeping slowly down the bank.

The parking brake – hadn’t she set the parking brake? Your mind worked over that single detail as if you could go back in time and make her set it.

The car picked up speed, crunching over gravel.

“Oh no,” Harmony said, a little further down the shoreline. Then the car went over the bank, nose first, into the river. It dipped like a soft ice cream cone in chocolate, then bobbed back up and tilted back upright – for just a moment you wondered if it would float. Then the front of the car began sinking, moving forward like someone easing downhill.

The rest is a blur, as hard to remember clearly as it is impossible to forget, a slideshow of adrenalized flashes: Running. Splashing. Screaming.

Of the four of you, it made sense you’d reach the car first. You’d grown up on that river. Lifeguarded the summer before at Cannon Pool. You made your way across slippery rocks, current tugging at your clothes, Harmony screaming behind you, the car drifting away, pointing down like a sinking ship. The hood was already underwater, river starting up the windshield by the time you got to the passenger window Harmony had left partially open.

The water was at your chin. You could just get your arms through the window but you couldn’t reach the back seat. “Morton! C’mere!”

Morton was awake, sitting on the backseat, chewing his pacifier as water swirled around his legs. He stared at you and all seemed lost, and then he crawled across the wet back seat and into your arms – otherwise –

You can’t think of the otherwise. Even now.

You got his little head sideways through the car window, scraping it on both sides – only then did he start crying. The rest of his body slid through like a mocking version of birth itself. You held him against your chest.

You’d end up having three yourself, Meghan the youngest – but no child ever felt better against your body. The car lurched forward, water rushing through that open window.

Harmony had reached you by then – “Oh my god, Morton!” – and you handed her child over. Patrick was at her side.

Only then did you look back to shore. It’s not like you expected Joey to save the kid. But something about him standing alone on the shore, clothes completely dry, told you all everything you’d ever need to know.