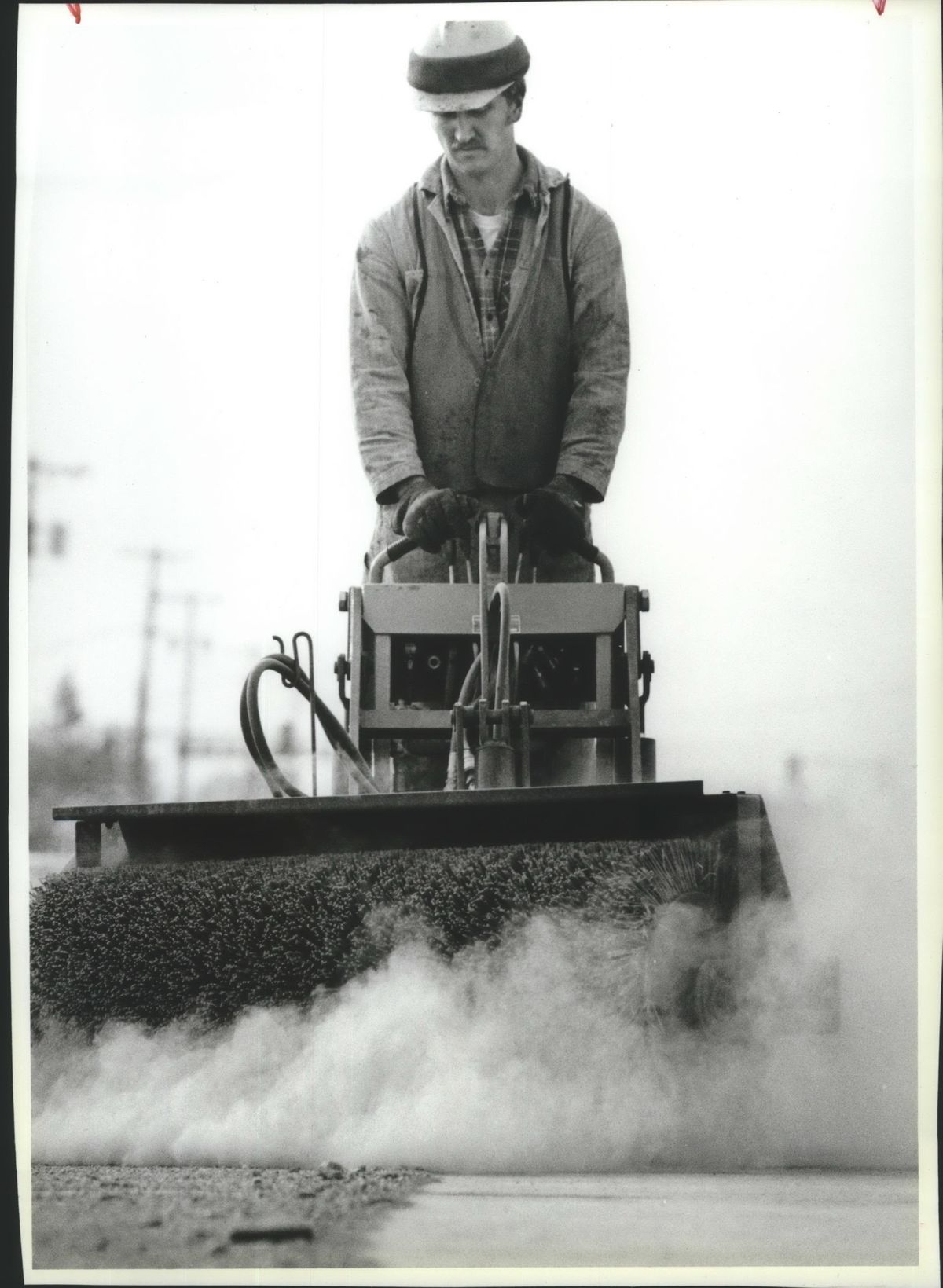

Getting There: Smoke plagues our air today. A quarter-century ago, it was dust.

You can’t blame automobiles for the poor air quality – not this time. The foul air that has been draped over Spokane for the past week is the result of raging fires north of the border in Canada.

While our vehicles collectively remain the largest source of air pollution and greenhouse gases in Washington state, 25 years ago the problem wasn’t the tinder in our forests or the fumes from our exhaust pipes.

It was road dust.

In 1964, the city had eight street sweepers, and city street-cleaning crews worked alongside “welfare recipients,” according to an article in the Spokane Daily Chronicle.

“A dozen men on welfare rolls were being used to sweep, with hand brooms, excess gravel which can not be picked up by equipment,” the article read, estimating that year’s street cleanup would take “a full eight weeks” due to the large amount of sand the city spread over the winter.

These were the halcyon days of winter road traction and clean pavement.

By 1983, the city was spending $1.1 million a year to keep the streets clean, but trouble was in the air.

Around this time, the city had 180 miles of unpaved roads, and their dusty state was already known as a contributor to air pollution. So was street sweeping. The city and region were struggling to meet federal air quality standards, but there was no real cudgel to compel the city to comply with the rules. The city paved a required number of unpaved lane miles, monitors continued to show elevated levels of air pollution and nothing much happened.

A decade on, however, things changed.

In 1991, street sweepers collected more than 15,000 tons of sand from the streets – about the weight of 7,500 cars. That’s a lot of sand, and it led to a lot of trouble.

The year before, the 1990 Clean Air Act had passed in Congress and it wasn’t long before its regulators knocked on Spokane’s door to deliver some tough news: The region was at risk of being labeled a “serious PM10 nonattainment area.”

PM10 refers to the size of particulate matter in the air. In this case, it means the particles are 10 microns or smaller. They’re not as hazardous as PM2.5, which come from wood burning and can infiltrate the bloodstream, but they’re still harmful.

In other words, Spokane had an air quality problem, the feds wanted it remedied and the culprit had been identified years before: dusty roads.

In 1993, a Spokesman-Review article titled, “Snowy winter makes for dusty spring,” described the situation. About 30,000 tons of gravel was put down countywide to combat the particularly harsh winter’s 86 inches of snow. It was everywhere. And it was dusty.

“Those walking or bicycling may especially notice the dust wafting from the road surfaces. It was severe enough Wednesday to push air pollution monitors far above normal, said Ron Edgar of the Spokane County Pollution Control Authority,” it read.

One air sensor located at Country Homes Boulevard and Division Street registered a level five times the federal limit.

“If we only have one day of road dust problems, we’ll probably be all right,” Edgar said at the time.

A county planner who biked to work, Tom Veljic, told the paper, “It’s terrible – it’s just dust city.”

In another article, Eric Skelton, director of Spokane County Air Pollution Control Authority, suggested the federal rules put outsized responsibility on local government.

“The fact that we are out of compliance with PM10 standards is because we have dust from unpaved roads, from traction sand, dust storms and a wood stove problem,” he said. “We can probably fix street sweeping. But, if Spokane is held accountable for all the windblown dust, you’re talking about stopping 80 percent of the dust coming in. Mother Nature blew it here in the first place.”

But the data didn’t really back Skelton. It showed that Spokane’s air quality plummeted precipitously for a three- to five-day stretch at the end of every winter. Just as the streets dried out to release the dust from the traction sand.

Facing a federal slap and worried about chasing industry away with a “nonattainment” designation, lawmakers at the city and county passed resolutions to change their street cleaning standards. They would use less sand and sweep more often. Liquid de-icer would be part of the plan to keep winter roads navigable.

The city said it would sweep major roads two to six times a year, and residential roads one to three times a year. It would reduce the use of sand by half, and use a higher quality gravel that had fewer smaller particles. It would plow more to reduce the need for de-icer and traction material.

The feds applauded. Such changes would go a long way. But that left the tricky problem of paying for it all.

In the fall of 1993, local lawmakers put the onus on voters and in November the ballot had a countywide gas tax of 2.3 cents per gallon. The tax was expected to generate $4.4 million in 1994, money to be used exclusively for street sweeping, street paving and de-icing programs. The city said it was committed to doubling its street cleaning force by hiring nine more employees, buying 11 sweepers, six flushers and other new equipment to replace sand and gravel efforts with liquid de-icers.

Voters were unmoved.

On Nov. 2, voters rejected the gas tax. Instead, to pay for its new street cleaning plan, the city said it would have to cut back on other services, such as pothole repair and snowplowing, to ensure Spokane had clean air.

Before those cuts, that December, the City Council considered a utility fee to finance street cleaning and liquid de-icing. Once a month, households pay an additional $1.40 on their utility bills. An article in The S-R said the effort was “steamrolled” by “opponents of higher taxes.”

Councilman Orville Barnes said the city was being forced by a “bureaucratic dictatorship” to pay more for street cleaning and warned of a revolt. George McGrath, still an anti-tax fixture at council meetings 25 years later, said, “We do not need additional taxes.”

With both the gas tax and utility fee defeated, the governments of Spokane went looking for money elsewhere in the road budgets to keep the air as dust-free as possible. Potholes went unfilled. Snowplows didn’t do as much. But the dust had been dampened. In 1994, the Spokane area had cracked the problem and showed “attainment” of air quality standards, at least when it came to PM10.

The cities of Spokane, Spokane Valley and Millwood, as well as the unincorporated areas of the county, all still have agreements in place with the Spokane Regional Clean Air Agency regulating street cleaning procedures. The agreement, and related plan, expires in 2025. The agreement only covers the federally designated “maintenance area” of the central, urbanized county, and doesn’t include Liberty Lake, Airway Heights, Cheney or other far-flung corners of the county.

It’s cold comfort to know that larger particulates have been largely controlled while we were warned to avoid going outside. So where are we now? It’s mid-August, the world’s on fire and there’s still plenty of traction material on the streets of Spokane.

Marlene Feist, director of strategic development for the city’s public works department, said the city spends $2.5 million on street cleaning, and it uses a cleaner, “higher-washed” traction sand than it did 20 years ago. It put down about 2,000 tons of sand this past winter.

It would be a fool’s errand to estimate how much sand is still left on the streets, but it’s safe to say that the city still has work to do. Logistically, Feist said, it’s difficult to sweep more than it does, which amounts to twice a year for arterials and once for residential streets.

“To do more would require a larger budget and more people assigned to the task. Possibly additional equipment,” she wrote in an email. “Our street department also fills potholes, picks up leaves in the fall, plows snow and performs deicing, replaces signage, repaints all the street markings, and completes a series of grind and overlay and other repair projects each year, in addition to sweeping. We balance all those tasks with the funding we have available.”

As for Spokane’s unpaved streets, there are still 60 lane miles of them in the city, out of 2,200 total miles of streets. The city is still working to pave them all.

Travel on Sunset Highway west of the city remains restricted to one lane in either direction as the city rebuilds the road.

When complete, the old road will have two 12-foot-wide travel lanes going uphill, one 14-foot travel lane and bike lane headed down and a 12-foot pedestrian and bicycle path on its northern curb.

The $2.5 million project is giving new life to the road between the intersections of Royal and Lindeke streets with a fresh paved surface. It will be completed this fall.

High Drive between 21st and 29th avenues on Spokane’s South Hill is closed for work to replace a sewer line.

The $1.5 million project will install a 30-inch sewer pipe and lay new pavement. An 8-foot-wide pedestrian path is being installed, one similar to the path along High Drive farther south.

Sharp Avenue near Gonzaga University continues to get a major facelift, with the city using new methods to treat stormwater.

The nearly $2 million project has fully closed the road from Pearl to Hamilton streets, as it adds swales and prepares the road for pervious pavement, which will allow stormwater to filter through it into the earth.

As of Thursday, the city had repaired 3,597 potholes. In 2017, it fixed 4,795, and in 2016 it filled 3,045.

The annual, statewide bicycle and pedestrian count is coming next month and the Washington state Department of Transportation and Cascade Bicycle Club are looking for volunteers to help tally those of us who shun the car at least every now and again.

This year’s count is Sept. 25-27.

The annual count is part of a larger national effort to document the number of people who use “active” transportation. Unlike automobiles, which are counted automatically, walkers and cyclists are tough to enumerate, hindering the ability to provide appropriate infrastructure for them.

Human eyes counting their numbers will help, and be added to the numbers collected by the state’s permanent counters. In Spokane, there’s a permanent counter on the Centennial Trail in Kendall Yards. So far this year, the counter has tallied 161,967 pedestrians and bicyclists there, 11,863 in the first 15 days of August. Another permanent counter on the Ben Burr Trail in the East Central neighborhood has counted 23,990 cyclists and walkers since the year’s beginning. Lastly, a counter on the Children of the Sun Trail near its current southern terminus in Hillyard has counted 9,763 people walking or biking.

For more information, and to volunteer, visit www.wsdot.wa.gov/bike and look for the “Bicycle and Pedestrian Count Project” link.