Book World: An enigmatic child sends a small town on a search for answers

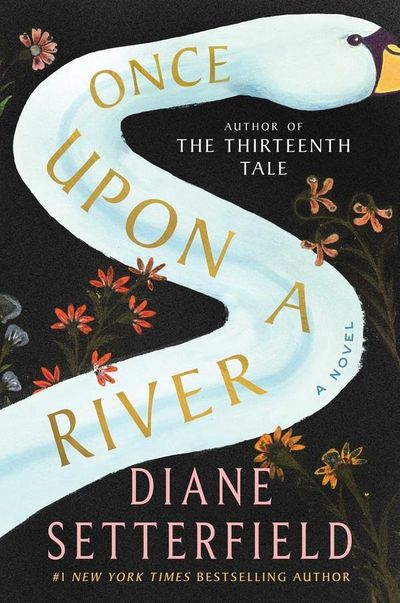

Diane Setterfield haunts familiar ground in “Once Upon a River,” an eerily mystic tale of a mute child who captivates the local townspeople after she’s seemingly brought back from the dead.

The author of “The Thirteenth Tale” and “Bellman & Black” begins this account on a winter solstice more than 100 years ago. A near-drowned stranger arrives at a rural inn, grievously injured and carrying a young girl who, to all appearances, has already died. Despite the child’s corpse-like state, however, the local nurse, Rita, discovers a pulse.

Though the girl is revived, the stranger lapses into unconsciousness and so the mysteries quickly stack up like branches snagged in the river: What accident befell him? How was he saved? Who is the child? How did she die and then live again?

Most importantly, to whom does she belong?

Three separate families lay claim to the girl: Helena and Anthony Vaughan believe she’s their kidnapped daughter; Robert and Bess Armstrong think she’s the illegitimate grandchild they would dearly love to welcome home; and Lily White hopes she’s the sister whose loss has drowned her in guilt.

These characters are finely drawn and wholly sympathetic, their lives rendered in precise, poignant detail. The female characters particularly are gifted with uncommon clarity, each of a different kind. Rita is a woman of science, Helena has strong emotional instincts, Bess is blessed with insight and Lily takes an unflinching view of practical realities.

Even so, each character lives in a state of profound denial, easing painful realities by telling themselves stories. Setterfield illuminates how such stories can be our most compelling forays into fiction. Even amid swirling doubts about the child’s identity, Helena so depends on finding her daughter in this lost girl that she builds an elaborate new world on top of the ruins of her old life, with the mute girl at its center.

At different points the narrative emphasizes the powers of oral tradition, photography and performance, using stories that straddle fiction and fact to reveal essential truths to the speaker and the audience.

The river acts as both setting and character, a force in the everyday lives of its neighbors. Though Setterfield writes emotions with marvelous truth and subtlety, her most stunning prose is reserved for evocative descriptions of the natural world, creating an immersive experience made of light, texture, scent and sensation.

The timeline is slippery, flashing back at length and jumping months ahead. Though each branch of the story is well served, we spend some intervals away from each character. Rather than resenting these diversions, however, the reader finds herself yearning for the updates the next chapter will bring.

The novel’s central mysteries are dispatched in one dramatic scene that feels overwrought, especially given that this is not a tightly plotted whodunit so much as a story for those who appreciate the tale’s telling as much as its end – who mark with interest the bends in the river, and who will treasure the friends they bump into along the way.