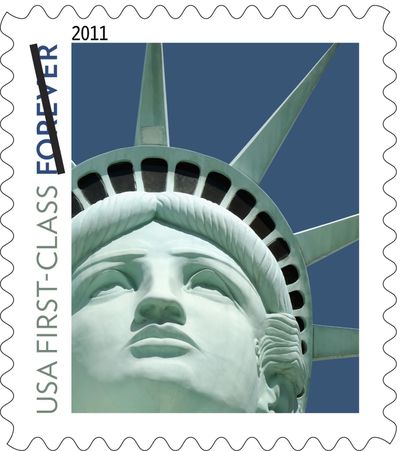

USPS must pay $3.5 million after confusing Statue of Liberty with ‘sexier’ Las Vegas replica

They sounded like one of those perfect romantic odd couples at first – the kind you can’t understand how they even hooked up, but they seem so great for each other. The U.S. Postal Service and a half-size replica of the Statue of Liberty – from a Las Vegas hotel, no less.

They met totally by accident. The Postal Service thought she was the real statue and put her picture on one of its most popular stamps. It was like the premise of a rom-com. But the best part was, postal officials wanted to stay with the image even after realizing the mistake.

“We still love the stamp design and would have selected this photograph anyway,” a Postal Service spokesman told the New York Times in 2011. And USPS went on to feature the Las Vegas knockoff’s sultry lips and retro-modern bangs on billions of stamps for years to come.

“Forever” stamps, USPS called them. As in happily ever after.

But that was before the breakup, and the court fight, and before all the ugly details became public.

And now it’s over. Last week, a federal judge ordered USPS to pay the statue’s creator $3.5 million for exploiting the sculpture without permission or consent.

So much for love stories.

When thing started to go bad, some people blamed the statue.

More exactly, they blamed the artist, Robert S. Davidson. He sued for copyright infringement in 2013, claiming USPS had sold billions of the stamps, even after the government realized it had confused an image of his plaster sculpture at the New York-New York Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas for the 19th-century stone-and-copper behemoth off the shore of the real New York.

The stamp was extremely popular with the public by the time Davidson sued. He might not have done himself any favors, PR-wise, by calling his sculpture “fresh-faced” and “even sexier” than the original Statue of Liberty.

“Mr Davidson, you are truly gross,” a representative angry commenter wrote beneath the Washington Post’s first story on the lawsuit in 2013. “You take an icon of America, create a low-level, cheap looking semi-replica for, of all places, Vegas (our national seat of cheap, shallow self-indulgence), make money off this, then cry copyright infringement. Are you kidding?”

But Davidson told a more compelling story at the trial last year – or he at least found a more receptive audience in a federal claims court judge.

After failing to convince the court that Davidson’s statue was a building, not a sculpture, and therefore exempt from claims of artistic infringement, USPS argued that it simply wasn’t original. Davidson had simply copied a government-owned statue, the mail service argued, and therefore USPS could freely design stamps based on his creation as if it was using the real Lady Liberty.

To dispute that, Davidson told the court how he created the sculpture.

And here, the story gets a bit romantic again.

Davidson took on the $385,000 job in 1996, after completing his work on a 110-foot replica of the Sphinx down the street from the New York-New York. The hotel wanted him to make a to-scale version of the real Statue of Liberty, he told the court. But he was given no scale model to work with, so he had to improvise his own design.

“I just thought that this needed a little more modern, a little more contemporary face, definitely more feminine,” Davidson testified at the trail, according to court documents. “Just something that I thought was more appropriate for Las Vegas.”

As inspiration, he said, he used a picture of his mother-in-law.

The judge noted that Davidson seemed to speak with genuine emotion as he recalled how he rasped away the plaster to reveal the statue’s face – bringing to life its eyes and what the artist called “little subtle touches on the lips.”

“It really starts to speak to you and kind of tells you which way it’s got to go,” Davidson told the court. “And it tells you if you do it wrong. It really does.”

When he finished the 150-foot sculpture, the judge wrote, Davidson affixed a small plaque to a spike on its crown. “This one is for you, mom,” it read.

Fifteen years later, Davidson said, his wife came home from the post office to tell him that the plaque, and same face, was being sold for 44 cents a stamp.

A spokesman for USPS decline to comment on the case. As federal judge Eric G. Bruggink described it, the government did not offer much in the way of a compelling defense.

A bad caption on an online photo of Davidson’s sculpture led to the government’s initial confusion, per the court. USPS’s manager of stamp development had been searching for a suitably patriotic image to replace a popular Liberty Bell stamp in 2010. He was captivated by what he called a “different and unique” low-angle shot of the famous Lady Liberty – without realizing that the photo had been taken at the corner of Las Vegas and Tropicana boulevards.

So USPS paid Getty Images $1,500 to license the photo, turned it into a stamp-sized illustration, and cranked it out of printing presses by the hundreds of millions.

“Lady Liberty, as the Statue of Liberty is affectionately known, is shown in a close-up photograph of her head and crown,” the agency wrote in a December 2010 press release, describing the new stamp as its “gift” to business mailers.

The mail service knew within a few months that it had used the wrong Lady Liberty, the judge wrote. It was informed first by a photography company, then by a stamp collector’s blog post, then by The New York Times and The Washington Post and many others.

But after some internal discussion, the judge wrote, USPS officials decided to keep selling the stamp, which the government had already spent millions of dollars to print and distribute – and which had already proved so popular with the public that the stamp was known internally as the agency’s “workhorse.”

So USPS simply admitted the mistake, praised the design’s beauty, and went on to sell nearly 5 billion stamps for more than $2 billion before retiring it in early 2014, a few weeks after Davidson sued.

“The Postal Service offered neither public attribution nor apology,” the judge wrote in last week’s ruling. “ … Printing billions of copies and selling them to the public as part of a business enterprise – whether for use to send mail or to be retained in collections – so overwhelmingly favors a finding of infringement that no fair use can be found.”

Even with the USPS’s thin profit margins, the judge wrote, the government earned $70 million in profit during the stamp’s four-year run.

He decided that Davidson should get a 5 percent royalty on that, and so ordered the government to pay the artist $3,548,470 and 95 cents – plus interest, and affections notwithstanding.