Summer Stories: ‘Bargaining,’ by Stephanie Oakes

Dad never bought what could be bartered for.

“I bet I can pull that tumor from your brain,” he said to the elderly man gassing up the blue truck, a lacework of rust cupping each wheel well. “In exchange for that truck.”

“How did you know –” the old man sputtered.

“Yes or no?” Dad asked, in his serious way. The sun glanced off of his leathery skin comfortably, as though embracing an old friend.

The old man nodded, jerkily.

My father pinched the air before us, and in the next moment, a bloody oblong of flesh was nestled loosely in his fingers. The old man could only halo his hands around his head, awe-struck, while we peeled the truck from the parking lot.

“Wooo-wheee!” Dad shouted as he sped down the street, adjusting the mirror to his much smaller height. “What do you think about that, son?”

I pursed, arms folded across my chest. “What is that man supposed to do now, with no truck?”

“What difference does that make?” Dad demanded. “We needed a truck for the trip and he’s gonna live another 10 years. Everyone’s happy.”

I shook my head. Our house was stuffed with things my dad had won in bets and bargains, most of it completely useless. A moldering stuffed fox, a BB gun with the words “The Shlong” burned on the wooden stock, a Bible dedicated to someone named “Precious Tobin, on your sixteenth birthday.”

“Why do you have this?” I’d ask him, and his answer was always of the same variety (“I won it when a guy said I couldn’t hit a baseball through the side of the water tower.”).

Dad did things that nobody else could. But like all magic, by the time I was a teenager, I’d grown used to it. Grown embarrassed by it. And so it was with desperation that my father devised the road trip, hoping to unearth the son who’d once gasped in delight when he’d turn the water from our tap into chocolate milk or make the grasshoppers in our backyard play Vivaldi.

That August, wildfires burned so close to town, birds fell from the sky in droves, the nut-brown bodies of sparrows strewn across lawns like maple leaves. It wasn’t clear whether they died because they’d breathed too much smoke, or if it was from the shock of seeing their world so completely altered. The sky had turned orange, the sun like something from a child’s theater production, a construction paper disc suspended weirdly above the horizon.

We drove out of town thinking we’d outrun the fire, but we found it everywhere, erupting in columns behind mountains, misting the air with brown-colored smoke, falling in drifts like snow that has forgotten itself completely.

The truck’s cabin air filter wasn’t up to the task of separating clean air from the exhaust of burning forests, and there was no AC besides, so we spent the entire trip with the windows down, buffeted by the wind, our lungs growing heavy.

A bird’s lungs are different from ours. Dad taught me that on this trip. He told me every detail of their connected air sacs, gem-colored beads strung together around their miniature bird hearts. He used to hunt birds, he told me, from the cottage he lived in before he had me, back when he used to be something slightly wild.

“Before you met my mother?” I asked him.

He shook his head. “You don’t have a mother. I’ve told you.”

“I have to have a mother. It’s biology.”

He tucked his knobby chin, gripped the steering wheel, remained silent.

I knew that my dad wasn’t my biological father. We looked nothing alike. I was long and lean – “princely” he called me – while he stood below my shoulder, his back bending in an arc, muscles gnarled like old wood. In grocery stores, people would glance between us, trying to unknot the mystery of how we were related. When I was little, I’d yell, “He’s my dad, OK?” but not anymore. Because I knew that wasn’t exactly true. Because he refused to tell me where I’d actually come from.

We drove all day and found a campground outside the kind of small, Montana town that erupts every few miles on I-90. He set up a fire and a cooking pot. I unfolded the accordions of our camp chairs and sorted through our fishing tackle.

“I bet I can eat an entire jar of PowerBait,” I said.

Dad examined the fluorescent purple swirl of bait dough, flecked with geometric silver sparkles. Even with the lid closed, I could make out the nauseating fishy scent. He held his tongue between his teeth, considering. “What’ll I get if you lose?”

“I’ll wear your convertible hiking pants,” I said. “In public.”

“There’s nothing wrong with my pants.”

“No one – no one – ever needs to suddenly be wearing shorts that quickly.”

He smiled slightly. “And if I lose?”

“If you lose,” I said, “you have to tell me –”

“Forget it,” he said, his face darkening as he stood from the fire, climbed into the blue truck, and drove out of camp.

He didn’t return, not even after the campfire burned to cinders and darkness fell, the wildfires blazing on the faraway hills like veins of gold inside rock. I walked up the road, into town, to a gas station where I knew I’d find the blue truck parked. Attached to the gas station was a small casino, illuminated only by the glow of slot machines and red rope lights spanning the ceiling, coated in snake-like drifts of dust.

There my dad stood, not at one of the automated machines where others mechanically slotted their credit cards again and again, but in front of a man. Bargaining.

“Alright, little guy,” the man said, his expression amused. “I don’t know why you want that couch so badly. But sure, show me your magic trick.” The collar of the man’s shirt was buttoned too tightly, his neck overhanging the band like over-proofed dough. His name badge described him as, “Mick, Owner.”

Dad closed his fist, tight enough so the blood evaporated from his knuckles, and unfurled his fingers slowly. Inside the cage of them, a bright yellow canary had appeared. The man fell backward in shock.

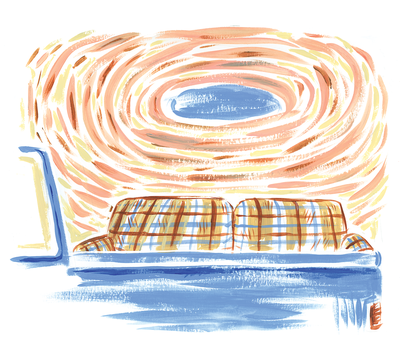

“Pleasure doing business,” Dad said, loosing the canary to wind circles around the dimly lit ceiling. “Come on, son. Help me lift it.” He indicated a worn, beer-stained couch, a resting place for long-haul truckers and casino patrons who’d burned through their money.

“We don’t need a couch,” I said, not moving. “We already have three couches.”

Dad shook his head. “I won it.”

“Wait a minute,” the man said, stepping close. “You’re not taking that. It’s expensive. It’s mine.”

“You, sir, made a bargain,” Dad said.

“Then make me another one.”

“That’s not how this works.”

The man thrust a meaty finger it into Dad’s chest, causing him to stumble backward a step. This guy could break Dad across his knee, easy as a yardstick. “Make me something more valuable than a bird. Turn something into gold.” He jammed his finger into Dad’s chest again, hard. “Make me rich.”

Dad’s face attained a manic glow. “If you like.”

I stepped forward to stop him, but not before the man’s outstretched finger began to change, cell by cell, from ruddy, wrinkled flesh to the dull yellowy sheen of real gold. The man registered it slowly, his lungs inflating. By the time he started screaming, gold was already winding through his body like a cancer.

“Help me with the couch, son!” Dad hissed. “Quickly!”

I looked between him, the couch, and the man. I could only shake my head, horror-struck, wanting no part of this. I watched him struggle to drag one end of the couch out of the casino, into the darkened parking lot where the truck waited.

“Why?” I shouted after him. “Why do this? All for a dumb couch.”

He let the couch fall into the gravel, panting. “It’s about more than a couch,” he said, his features barely distinguishable in the low light of far-off wildfires.

“Then what’s it about?” I demanded.

“It’s about victory,” he said. “It’s about being better than them.”

“Well, I’ll never win a bet with you,” I shouted. “So, just tell me. Tell me who my mother is. Tell me where I came from.”

“I won you, alright?” he said in a burst of speech. His expression stretched in surprise, as though he couldn’t believe the words that had fallen from his mouth.

“What?” I gasped.

“I won you in a bargain,” he said, quieter. I stood utterly still as he told the story, how he helped a girl who was down on her luck, how he spun a roomful of straw into gold. How he bargained for her baby. How she lost me to him. All because my mother couldn’t guess his strange name.

I recoiled from him, my shoes making trenches in the gravel. “You won me, like a – like a poker chip?”

“I won you like a prize,” he said, his eyes crumpling, imploring me to understand. “Like a grand prize – the only prize I’d ever want.”

“So my real parents –”

“Are rich assholes. You would’ve been miserable,” he said. “I’m the one who raised you. The moment I saw you, I knew you were my family. I knew you were my son. I did what it took. To win you.”

The air was choked with smoke, and maybe that’s why my eyes started streaming, or maybe it was how, when I considered him, all 4-feet-something of him, all leather-like skin of him, all wild hair and wide ears and long nose of him, I understood that we really were nothing alike. He was strange, and slightly frightening, and really goddamn embarrassing,

There was never anyone I belonged to more.

Wordlessly, I kneeled, fitting my fingers beneath the couch, and helped him negotiate it into the truck bed.

The next day, after we drove home and unloaded the couch into our overstuffed living room, the fires began to calm. I ran into the yard and craned my neck upward. A porthole of blue shone in the center of the sky for the first time in weeks. Still, I knew, even then, that the couch would never stop smelling of smoke.