50 years later: Days after Robert Kennedy’s Spokane election office opened, he was gunned down

Susan Lehinger remembers the first time she saw Bobby Kennedy in person.

“He probably had the saddest eyes of anybody I’d ever seen,” Lehinger, now a retired college professor, recalled recently. “He looked young from a distance, but up close his face was tremendously lined.”

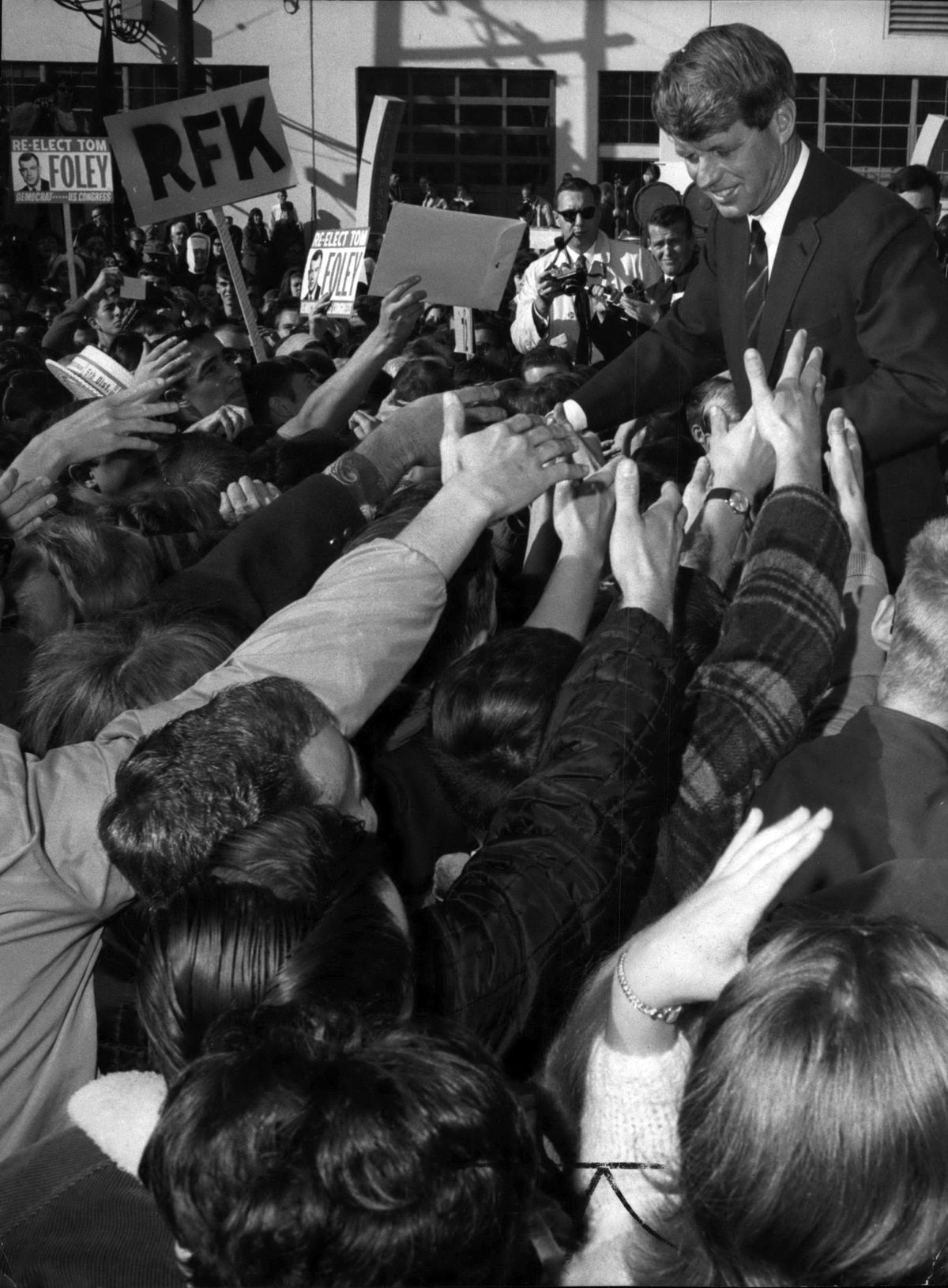

In October 1966, Kennedy, then a U.S. senator for New York, had come to Spokane to campaign for its Democratic freshman congressman, Tom Foley.

Lehinger first got involved in politics working for John Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1960 and stayed active in local politics. She was devastated by the president’s assassination in 1963 but worked for Foley’s upset victory in 1964 and was part of the campaign to keep him the seat.

The freshman congressman was in a tough re-election fight against Republican Dorothy Powers, who’d had a recent visit from former Vice President Richard Nixon.

Lehinger had written Bobby Kennedy a letter saying how sorry she was that his brother was killed, and he sent her back a handwritten note on a card from the 1963 funeral. The first time she met him, though, was when he came for the 1966 rally at Spokane Community College during his swing through the West for congressional candidates.

News accounts said a crowd of 600 waited to greet Kennedy at the Spokane International Airport the night before the rally, and an estimated 5,000 showed up for the rally. Kennedy told the crowd they needed to send Foley back to Congress to continue to making the kind of difference his brother talked about as president. When he spotted some people with Powers signs in the crowd, he joked that it was wonderful they had come to learn.

“Just think, if you hadn’t come you might continue to support Mr. Foley’s opponent without knowing any better,” he said, according to news accounts.

After the speech, Kennedy and Foley stood up in the back of a convertible, shaking hands from the crush of students who swarmed the car, and accepting a cake from the SCC baking class.

1968

By the spring of 1968, Bobby Kennedy was drawing crowds like a rock star for his run for president. The nation was convulsed over race, war and poverty.

Mounting casualties in Vietnam fed a growing anti-war movement. Military predictions of progress in the war were undercut by the massive Tet Offensive by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops in January. The United States and its allies actually won the military battle of Tet, but lost the public relations battle.

Sen. Eugene McCarthy, a Minnesota Democrat running on a peace platform, dealt President Lyndon Johnson’s re-election bid a mortal blow in the New Hampshire primary in March, and LBJ made the surprise announcement on national television at the end of that month that “I will not seek, nor will I accept, the nomination of my party for president.”

A few days later, Bobby Kennedy entered the race for what some believed was the continuation of his brother’s ideals and others thought was for the salvation of America. Some American cities had burned the summer before with race riots, and civil rights demonstrations continued throughout the South.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. went to Memphis in early April to help lead a march in support of the city’s striking garbage workers. The night of April 3, he gave his “I’ve been to the mountaintop” speech. The next evening he was shot dead by a sniper while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Riots broke out around the country.

Kennedy was campaigning that evening in an African American community in Indianapolis, where the crowd didn’t know King had been shot. His aides urged him not to tell the crowd, fearing a riot, but Kennedy did, and then talked of King’s efforts to replace violence with compassion and love. While they might be filled with anger because King had been shot by a white man, he said, so had his brother.

“What we need in the United States is not division, what we need in the United States is not hatred … but love and wisdom and compassion toward one another,” he said, adding later he hoped they would dedicate themselves to an ideal of the ancient Greeks “to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world.” He asked the audience to pray for the country and its people, and the crowd dispersed quietly.

Kennedy went on to win the Indiana primary, but lost the Oregon primary to McCarthy. Vice President Hubert Humphrey had LBJ’s support. The campaign hinged on California’s winner-take-all primary on June 4.

Spokane for RFK

When Bobby Kennedy got into the presidential race, Susan Lehinger knew she wanted to help, even though she was a mother with small children and had returned to college.

“I heard the talk about him being presumptuous to get in and cause McCarthy problems. I didn’t believe it,” she said. “I saw what he did when Martin Luther King was assassinated.”

Through her party work and contacts, she knew Kennedy’s Washington state campaign chairmen, Frank Keller and Jim Whittaker. She became the Spokane campaign manager, with another longtime local Democrat Bob Dellwo as the Eastern Washington manager. The downtown Spokane office opened just a few days before the California primary.

It had received some campaign materials like boxes of literature and some copies of his speeches right after opening but no buttons or yard signs yet. Washington used the caucus system and Kennedy had plans to come to the state convention in July to pick up delegates for the final nomination battle at the national convention in Chicago.

“We were just getting organized,” she said. “We had all kinds of good plans.”

Lehinger believed Kennedy was the right person to lead the country through what she describes as “a terrible time.” Between the protests for civil rights and the anti-war demonstrations “you were just uptight all the time.”

Protests in the streets, on campus, at the Mall

The two months between the King assassination and the California primary were among the most contentious in America since the Civil War. Although Kennedy calmed the crowd in Indianapolis, riots broke out in 100 cities.

Student protests over the war and secret contracts for defense work closed Columbia University in New York, and demonstrations spread to other campuses.

Coretta Scott King led a Mother’s Day march in Washington, D.C., to demand an economic bill of rights. The Poor People’s Campaign by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference set up Resurrection City, a shanty town, on the Capital Mall later that month in an effort to get Congress to address poverty issues.

Rock songs about protest and revolution competed with tunes about surfing and romance on the radio. On June 3, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down most death sentences in the nation. The Viet Cong fired rockets into Saigon and North Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho landed in Paris for the beginnings of peace talks on the war. In California, Kennedy made a final campaign swing through San Francisco, San Diego and Los Angeles.

On June 4, he huddled with top advisers to watch returns in a room in the Ambassador Hotel while supporters gathered in the ballroom below. McCarthy led in the early returns, but Kennedy pulled ahead as vote counts from the major cities came in.

Kennedy went to the ballroom to thank his cheering supporters, reminding them the campaign wasn’t over.

Linking arms

In Spokane, Susan Lehinger watched the California returns on television late into the night with her husband, Alfred, until Kennedy made his speech. When he finished with “Now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there!” they turned off the television and went to bed.

“My husband said, ‘They’re going to kill him, you know,’ ” she recalled last week.

When they woke up the next morning, they heard on the radio Kennedy had been shot. When he left the ballroom stage, campaign staff had Kennedy take a shortcut through the hotel kitchen to get to a news conference. There Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian national who had written in his diary that Kennedy must be killed, was waiting with a .22-caliber revolver, which he emptied at the candidate.

“It was just so shocking,” she said.

Initial reports were Kennedy was clinging to life at the hospital. Lehinger went to the campaign office where other supporters were gathered. They got word of a special Mass at Our Lady of Lourdes Cathedral in downtown Spokane for Kennedy. They linked arms at the headquarters and marched to the cathedral to pray for him.

When they emerged after the Mass, they got the news Kennedy had died.

Aftermath

For the second time in two months, stunned Americans watched a nationally televised funeral and mourned. Thousands waited outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York on June 8 while the funeral Mass was held inside. The eulogy by his brother Ted Kennedy included one of Bobby Kennedy’s favorite quotes from George Bernard Shaw: “Some men see things as they are and say why? I dream things that never were and say why not?”

Washington state Sens. Warren G. Magnuson and Scoop Jackson, along with Rep. Tom Foley attended the funeral and rode the train that carried Kennedy’s casket back to Washington, D.C., for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. Hundreds of thousands lined the tracks to watch the train pass.

“I am shocked, dismayed, saddened and angry,” Magnuson told reporters. “But you cannot condemn 200 million people for the actions of a handful of the mentally deranged.”

The day before the funeral, Congress approved legislation to give Secret Service protection to presidential candidates. Johnson pushed them to approve legislation which would bar mail-order sales of handguns, which passed within days. Like today’s gun control legislation, it was denounced by opponents as an infringement on constitutional rights of law-abiding gun owners.

The day of the funeral, James Earl Ray was arrested in London for the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. He was traveling from Lisbon to Brussels on a forged passport, and had a handgun in his hip pocket. Later convicted, he died in prison.

Sirhan Sirhan eventually was convicted, and remains in prison.

With Kennedy gone from the race, his delegates from the primaries scattered, some going to McCarthy and others to Sen. George McGovern. But most delegates weren’t chosen by primaries in 1968, and were controlled by party officials, who lined up behind Humphrey.

When Democrats gathered for the national convention in Chicago, so did anti-war protesters from around the country. Police used clubs and tear gas to disperse protesters outside the convention center, while the protesters chanted “the whole world’s watching.” The riot outside competed with the convention inside, where Democrats nominated Humphrey.

Richard Nixon, who had been nominated by Republicans weeks earlier, ran on a law and order platform against Humphrey, whose campaign never really recovered from the Chicago riots. Nixon won convincingly in November.

An emotional time

Susan Lehinger said her heart broke for politics in June 1968.

“It was a highly emotional time for those who cared about what was going on in the world,” she said. “I was thinking, what’s the use, first John then Martin Luther King and then Bobby.”

Going to college pulled her out of that, and she went on to earn seven graduate degrees on subjects ranging from psychology to poetry. She worked with young people and later taught master’s programs at Fairchild Air Force Base. Her only political activity was working for Foley whenever he needed her.

Politics has changed over the last 50 years, becoming more partisan, she said, and it seems harder for elected officials to get anything done.

Lehinger still has some of the campaign materials sent to Spokane that volunteers never had the chance to distribute. And she still thinks fondly of Bobby Kennedy.

“He had more compassion in his little finger than most politicians have in their whole body,” she said.