Getting salmon above Grand Coulee Dam could lead to fishable population in the Spokane River, tribes say

Getting salmon and steelhead over Grand Coulee Dam could someday bring back a recreational fishery to the Spokane River, local tribes say.

Blocked areas above the dam contain hundreds of miles of spawning and rearing habitat suitable for steelhead and spring chinook production, according to the Spokane Tribe’s research.

If reintroduction efforts become a reality, future generations might be able to hook a salmon or steelhead in the lower Spokane.

The study looked at habitat on the Spokane and San Poil rivers, along with other tributaries of Lake Roosevelt, the reservoir behind the dam. The results also suggest a fishable sockeye population could thrive in Lake Roosevelt.

“It could potentially be thousands of fish,” said Steve Smith, a consultant for the Upper Columbia United Tribes, which represents five local tribes, including the Spokanes.

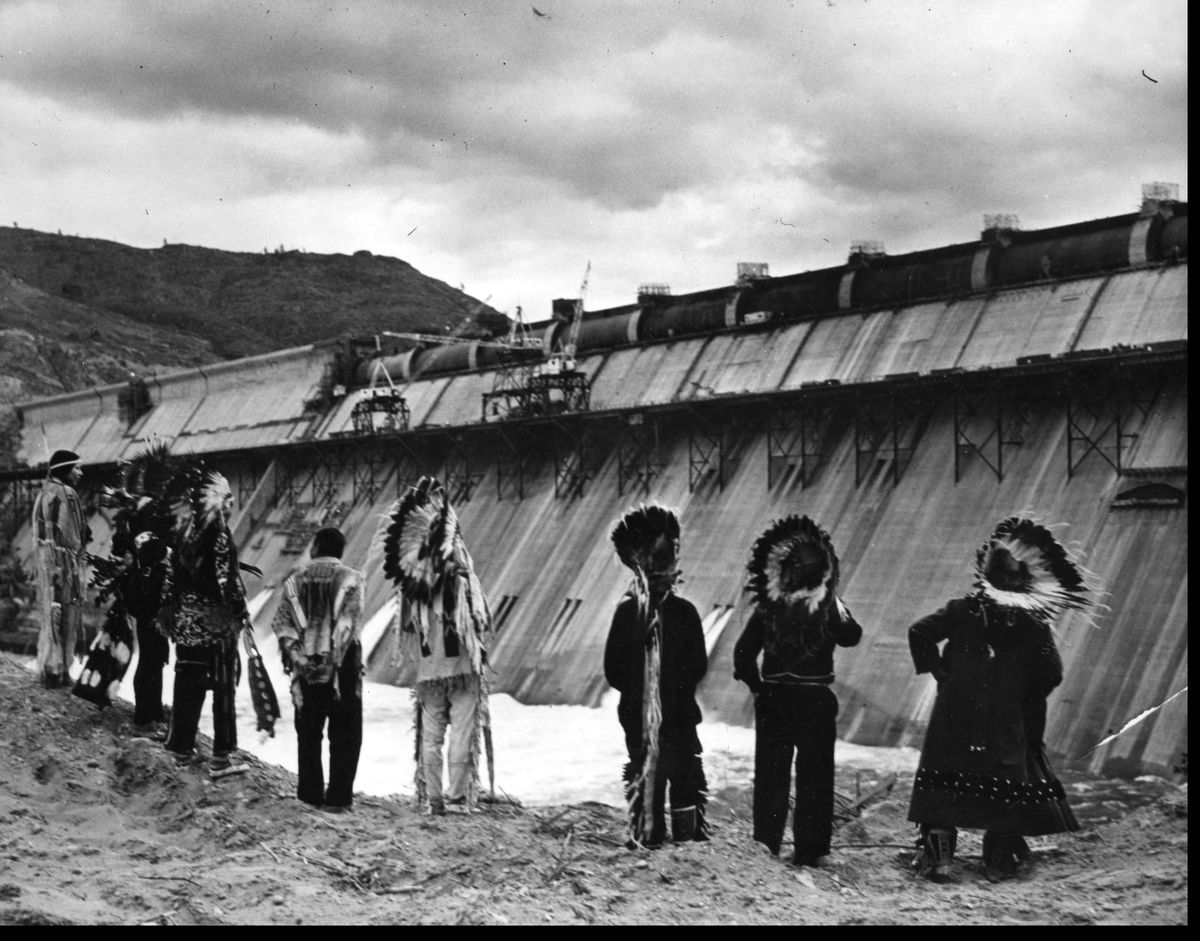

Elders still tell stories about the tears tribal fishermen shed as they watched salmon throwing themselves against the newly constructed Grand Coulee Dam, said John Sirois, a coordinator for Upper Columbia United Tribes. The dam blocked fish runs that once migrated up the Columbia River into Canada, providing a staple food for indigenous people.

“We think 80 years is too long to be without salmon,” Sirois said. “We see it as an environmental justice issue. It’s time to right some of those historic wrongs.”

Later this year, the region will get a better idea of what it would take to restore salmon and steelhead above Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams, both of which were built without fish ladders – Grand Coulee in the 1930s and Chief Joseph, about 50 miles downstream, in the 1950s.

The tribes released a “sneak peak” of a phase one reintroduction study at last week’s Lake Roosevelt Forum in Spokane. The study, expected to be out in 2018, looks at habitat and prospective donor stocks for reestablishing runs.

A second phase of the study would involve pilot fish releases and could require decades of research, Smith said.

New methods for trapping and hauling fish could get salmon above Grand Coulee and Chief Joe without the need for costly fish ladders.

On other rivers with tall dams, floating surface collectors called “gulpers” have been used. Powerful pumps create a flow that attracts fish to the collectors. Gulpers gather up salmon in the reservoirs so they can be trucked around the dams and released.

Because the collectors float on the surface, they don’t interfere with power generation, irrigation or flood control, Smith said. However, their success rate for fish collection varies. At some dams, it’s as high as 90 percent, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. At others, it’s as low as 40 percent.

Before white settlement, salmon traveled into British Columbia to spawn in the river’s headwaters at Columbia Lake. So, salmon reintroduction to the upper Columbia could eventually include getting the fish around Canadian dams, Smith said.

Ways to finance salmon restoration are under discussion, Sirois said. The tribes and federal agencies are already putting money into the studies. In the long-run, money could come from funds set aside to mitigate the effect of the federal Columbia Basin power system on fish and wildlife, he said.

Efforts to modernize the 1964 Columbia River Treaty could also be a source of funding, if the treaty is renegotiated with more emphasis on natural river function, Sirois said.

Climate change lends urgency to salmon reintroduction, he said. The Upper Columbia is expected to keep its snowpack and cool water temperatures, even as other parts of the basin become less hospitable for salmon, he said.

“Climate change is real, and we need to deal with it now,” Sirois said. “The river and the salmon deserve our action.”