An abduction by the mysterious Freemasons led to a 3rd political party – the nation’s 1st

William Morgan believed he had a big story to tell. What happened to him ended up being even bigger.

An itinerant stone mason and failed brewer cursed by what one critical observer called “a wonderful faculty for getting into debt and none for getting out,” Morgan, 52, turned his ambition to writing in 1826. He thought he had a seemingly surefire way to cash in on the conspiratorial zeitgeist that flourished in the early years of the 19th century and remains a hallmark of American politics.

Morgan was poised to expose what he said were the dark secrets of the Freemasons, a fraternal order that over the years counted 21 signatories of the Declaration of Independence and George Washington as members.

Almost 200 years before conspiracy theorists raised alarms about the “deep state” and claimed that mass school shootings were hoaxes, some Americans regarded the Freemasons as a sinister cabal that threatened the future of America.

The occasionally disturbing language of Masonic ritual as described by Morgan seemed to validate these fears. Applicants vowed to “(bind) myself under no less penalty, than to have my throat cut across, my tongue torn out by the roots, and my body buried in the rough sands of the sea at low water mark,” according to Morgan’s book. Candidates for the rank of third-degree Mason were required to acknowledge that failing to adhere to the order’s secrecy requirement would justify having “my body severed in two” and “my bowels burned to ashes.”

Morgan’s publishing plans aroused the ire of local Freemasons, some of whom apparently took their vows of silence literally rather than figuratively.

What happened next sounds like something from a Dan Brown novel.

As word spread about the book, Morgan’s prospective publisher was threatened. Morgan was jailed on trumped-up charges involving a debt of $2.69 and abducted upon his release, screaming “murder” as he was taken away, according to historian William Preston Vaughn. His kidnappers, Vaughn writes, were the head of the Masonic lodge at Canandaigua, New York, and two other Masons.

The aspiring author was never seen again and was widely believed to have been killed by his captors. Vaughn argues that they probably intended to smuggle him into Canada but killed him when that plan fell through.

Subsequent efforts over the next five years to prosecute those responsible produced a handful of convictions and sentences no longer than 28 months, which fanned the flames of anti-Masonic hysteria. “The question of one man’s fate was translated into public concern as to whether there existed a secret society powerful enough and to prevent punishment of the Morgan collaborators,” according to Vaughn.

The mysterious fate of Morgan animated an uneasy alliance of cranks and ambitious politicians and formed the basis of the first third party in the United States. The Anti-Masonic Party flourished in the late 1820s and early 1830s, before the partisan divisions of the antebellum era solidified into Democrats versus Whigs.

Members of Masonic lodges “are held in allegiance to an unauthorised government and code of laws,” Pennsylvania Anti-Masons warned in 1831. “(W)ithout attacking Masonry by means of the Ballot Box, where it is entrenched behind the political patronage and power of the government, all efforts to destroy its usurpations on the rights and privileges of the people must fail.”

Far from threatening republican government in the United States, Masons actually championed self-government, journalist Peter Feuerherd has written. “Many historians note that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights both seem to be heavily influenced by the Masonic ‘civil religion,’ which focuses on freedom, free enterprise, and a limited role for the state,” according to Feuerherd.

“The fraternity embodied European Enlightenment ideals of liberty, autonomy, and God as envisioned by Deist philosophers as a Creator who largely left humanity alone,” he wrote.

But where Masons saw benevolence, their foes saw danger. “At this very moment, its foot is on the neck of our liberties,” the Expositor newspaper of Wilmington, Delaware, editorialized in 1832.

In the aftermath of Morgan’s disappearance, legislative candidates who ran against the Freemasons showed surprising strength in New York, according to historian Charles McCarthy. As the National Republican Party led by President John Quincy Adams began to collapse, opposition to Freemasonry seemed to offer a viable basis for a new political organization.

Among those drawn to the movement was William Seward, then an aspiring young politician who rose to prominence in later decades as a Republican senator from New York and as secretary of state for President Abraham Lincoln. Seward was elected to the state Senate in 1830 as an anti-Masonic candidate and attended an anti-Masonic convention in Philadelphia later that year, according to Seward biographer Walter Stahr.

Adams was another prominent foe of Freemasonry. Although he stopped short of enlisting in the third party, he shared its suspicions. “That (Freemasonry) is a most pernicious institution I am profoundly convinced,” Adams wrote in his diary in November 1831, “and how it has arisen and grown, and spread over the world, and drawn into its vortex so many wise and good and great men is scarcely credible.”

Two months before Adams confided to his diary, a gathering of anti-Masonic politicians in Baltimore pondered the same question. The proceedings “were replete with reports and addresses on the self-assigned task of curbing if not extirpating Masonry as an element in the public life of the nation,” William S. Odlin wrote in The Washington Post in 1930.

Almost as an afterthought, the anti-Masonic delegates in Baltimore chose a presidential candidate – and in doing so became the first presidential nominating convention. William Wirt of Baltimore, who had served as attorney general for President James Monroe and Adams and prosecuted Aaron Burr, accepted the party’s nomination.

But he did so with profound ambivalence. Wirt admitted he had been a Mason as a young man. He was alarmed by what happened to Morgan yet refused to believe that it reflected on Freemasons as a whole. “But gentlemen,” he protested in the letter he wrote accepting the party’s nomination, “this was not, and could not be, masonry as understood by Washington. The thing is impossible. The suspicion would be parricide.”

If delegates found his views on Masonry insufficiently resolute, he assured them “that I should retire from (the nomination) with far more pleasure than I should accept it.”

They didn’t let him off the hook. In the end, Wirt carried only one state – Vermont – and soon the Anti-Masonic Party was well on its way to the oblivion that has awaited every third party in American history. As for Wirt, he became ill in early 1834 – and after undergoing the standard medical treatments of the day, including the application of leeches, according to historian William C. Robert – the one-time presidential candidate died in Washington on Feb. 18. But Wirt, who is buried in Washington’s Congressional Cemetery, returned to the headlines 170 years later in a ghoulish epilogue.

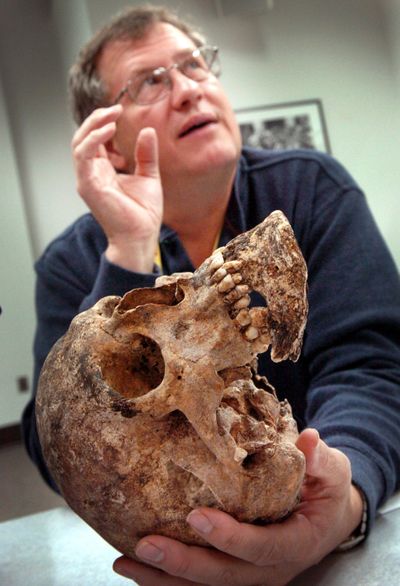

In 2004, D.C. Councilman Jim Graham contacted the cemetery to report that he had been given a skull in a tin box with the words “Hon. Wm. Wirt” painted on it, The Post’s Peter Carlson reported. Cemetery officials eventually took possession of the skull from Graham and arranged for a forensic anthropologist from the Smithsonian to examine it.

After entering the Wirt tomb and discovering that remains had been disturbed by grave robbers, investigators concluded that the skull was indeed Wirt’s. It was one of 40 owned by a collector who died in 2003, according to Library of Congress guest blogger Rebecca Boggs Roberts. The collector was not a suspect in the theft of the skull, which was probably taken in the late 1970s or early 1980s when the cemetery was in disrepair and thefts were common, Roberts wrote.

Evidence of Masonic evil, perhaps? Her conclusion would no doubt disappoint conspiracy theorists or fans of best-selling authors. “The answer to who stole William Wirt’s skull,” according to Roberts, “will remain a mystery.”