WSU Spokane scientists developing drug to ease tobacco withdrawal

Dr. Travis Denton chewed tobacco for more than 10 years before quitting cold turkey in 2001. He knows the jittery, anxious feelings that accompany nicotine withdrawal.

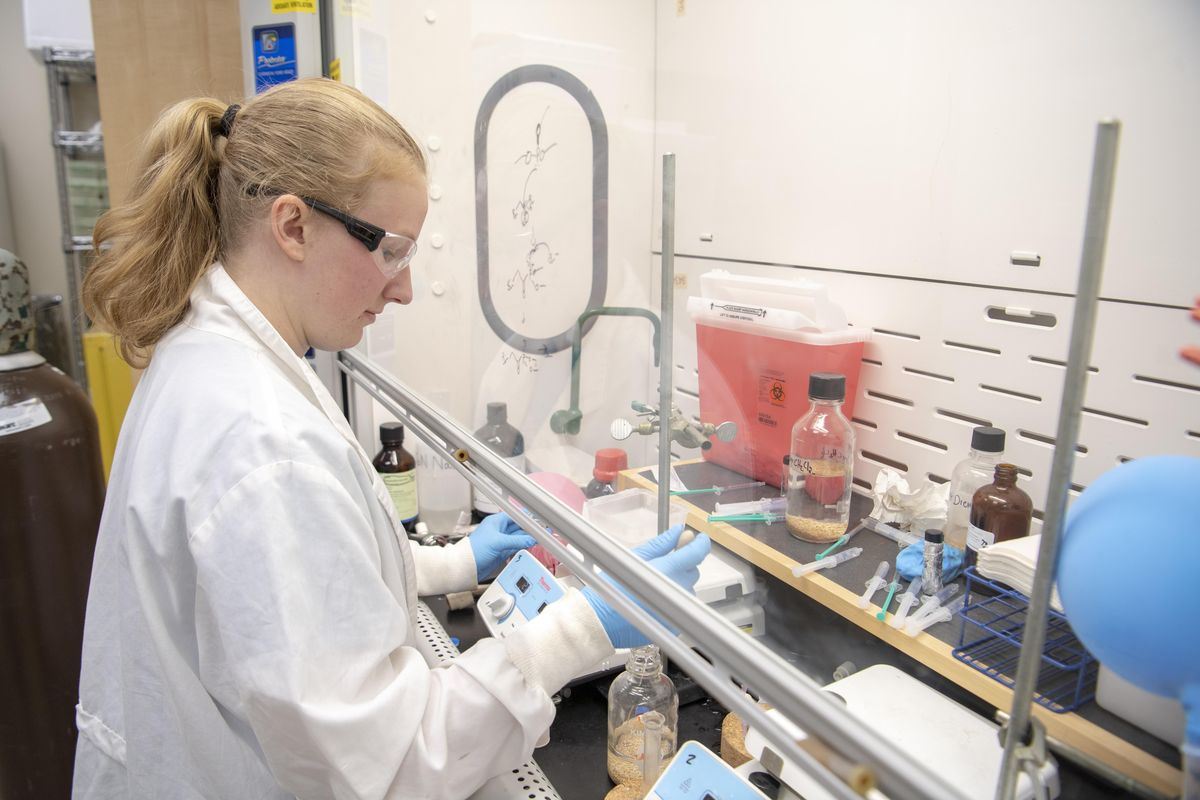

“It’s an addiction, the way I see it,” said Denton, 44, standing in his lab on the third floor of Washington State University’s College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Spokane, surrounded by vials and beakers, fume hoods and sketches of molecular structures.

Though he’s been tobacco-free for nearly two decades, Denton is reminded daily what a struggle it can be to quit. The assistant professor and researcher is developing a drug that, he hopes, will make that struggle easier.

“Tobacco companies will want to bury a drug like this,” he said.

Along with Dr. Phillip Lazarus, professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Denton has developed 18 versions of a drug capable of limiting an enzyme that metabolizes nicotine.

Their findings were published in the Journal of Medicine and Chemistry in July.

The scientists say they are confident in their results because their findings are already demonstrated in an already-existing test group: A certain portion of the population already lacks the gene responsible for the enzyme that their drug targets and suppresses.

“If people can have a normal life without having this enzyme, then that’s great for us,” he said.

When most people smoke, nicotine is metabolized by the enzyme, causing the body to produce dopamine and serotonin, causing pleasurable sensations. For those already addicted, being deprived of nicotine leads towithdrawal symptoms – tingling in the hands, sweating, anxiety, depression. At that point, smoking becomes a way to escape those, he said.

The drug under development delays the symptoms of withdrawal, giving smokers a chance to stretch the time between cigarettes, cut back overall and move more quickly towards quitting for good.

Some people will want to smoke even while taking the drug, but the drug will still work, Denton said, because “they could get the same feeling but smoke a lot less.”

The enzyme’s roll in addiction is supported by studies from Canadian researchers published in the mid ‘90s. That research suggested people who naturally produce less of the enzyme tended to smoke less, and were less likely to be addicted to smoking, according to a WSU press release.

“That was their idea, but they did it with a really bad molecule,” he said. “Our molecules are miles above theirs.”

Lazarus and Denton have been working on the project for the past 3 or four years, Lazarus said, and the drug has been tested on rodents with good results.

“We’ve gotten very positive results so far,” Lazarus said. “We don’t know how it’ll do when we try it in people.”

Lazarus compared his and Denton’s drug, which isn’t named yet, to Chantix, a drug that attempts to prevent people from smoking. Chantix targets the brain and has serious side effects like headaches, Lazarus said.

“We want to try to do something that’s a little less harmful to people,” he said.

The team is looking for grants from the government, and they have a patent on the drugs’ compounds, Lazarus said, but the last thing he wants to do is to sell the drug to a company that would prevent it from reaching the market and helping people quit smoking.

Companies like Pfizer “might try to buy it out and bury it. I wouldn’t let that happen,” he said. “We would rather start our own business or sell it to someone with better intentions.”

Other authors of the research paper include Pramod Srivastava, Zuping Xia, Gang Chen, Christy J. W. Watson and Alec Wynd.