Author, black historian Jerrelene Williamson to receive Spokane award after lifetime of storytelling

The way Jerrelene Williamson tells it, the mere presence of one of Spokane’s highest-profile lawyers in the room was enough to change the minds of administrators who were moving to close an elementary attended by many of the city’s black pupils in the 1960s.

“The parents were all sitting there, and we said, ‘Where’s Carl? Where’s Carl?’ ” Williamson, 87, said this week from her home at a retirement community in Spokane Valley. She was referring to the late Carl Maxey, the civil rights attorney who is credited with desegregating much of the region’s institutions in a lengthy legal career. “Carl opened the door and he came in, went over and sat with the parents, and I never will forget the school board members looked at each other and they said, ‘I don’t think we’ll close the Lincoln School.’ ”

The story elicits a chuckle and a smile from Williamson, who’s been telling these stories to reporters, community members and her own family for decades. On Wednesday, Williamson will receive yet another honor for her devotion to telling those stories, and through them illuminating life for the city’s black community, when she’ll accept the Community Impact Award from the Spokane Library Foundation.

Williamson, who literally wrote the book on African American history in Spokane, is a prominent character in her own stories. She traces her lineage back to some of the city’s first black residents, who migrated to Spokane from a defunct coal mining town after a testy strike in the 1890s.

Her great-grandfather, Henry Breckenridge, was a coal miner brought to Roslyn, Washington, by train from Virginia. He, and his black coworkers, didn’t know they were being brought in to break a strike, and when the white workers returned to the mines they remained skeptical of each other, Williamson said.

“But they carried their guns, both sides,” Williamson said. “If you act up, I’m going to act up.”

The family eventually migrated east when the coal mining work dried up, settling in Spokane. Williamson’s father was born here in 1899, but served as a railroad porter and met Williamson’s mother in Chicago. The family moved back to Spokane when Williamson was 2 years old, and she grew up in a home in north Spokane, near Rogers High School.

“I remember our neighborhood, we had a nice house out there on Broad Avenue,” Williamson said. “Most of the black people lived on the other side of town, on the south side. The lower south side.”

Williamson said her early years were spent partially oblivious to racial realities outside of Spokane, where the schools she attended weren’t segregated. She took part in singing competitions all over town as a member of the Rogers glee club, but it was a trip to Portland in 1948 that showed her some people, despite being far from the deeply racially divided South, harbored discriminatory beliefs.

“We went over there to sing, in the glee club, and I noticed that somebody was talking to my director, of the glee club,” Williamson said. “Then he came over to me, with tears in his eyes, and said, ‘Jerrelene, the girls are going to stay at the YWCA. We’re going to find a place for you in someone’s home.’ ”

Williamson gets upset about the story today not for her own situation, as a 16-year-old coming to terms with society’s treatment toward her race, but for her instructor Forrest Brigham, who was brought to tears by the situation. Williamson said she was asked to stay somewhere other than the YWCA out of concern she wouldn’t be served at the city’s restaurants, so instead the young glee club member stayed the night at a private home and ate with the family.

She later received a letter of thanks from the young couple who had invited her into her home. She kept that letter and wrote about it for The Spokesman-Review in 1997.

“I didn’t realize Portland was like that,” Williamson said. “I knew there was some discrimination here, but I had no idea that Portland was like that. I just never thought about it.”

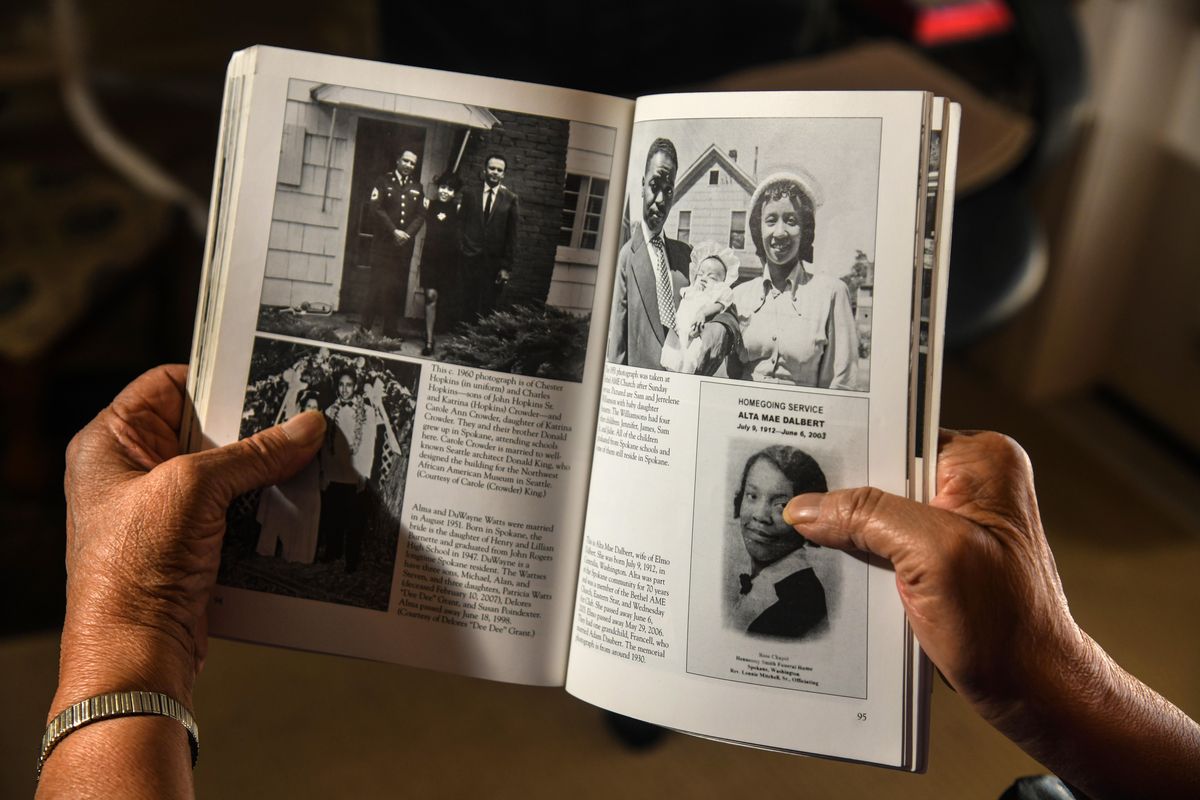

Williamson pieced together her own family’s history through historical records and the stories of her relatives. It’s all told, or mostly told, in the book she published in 2010 titled “African Americans in Spokane” through Arcadia Publishing, which includes historic photographs of herself, her family, Maxey and other prominent members of Spokane’s black community, including Mayor Jim Chase, the Rev. Percy “Happy” Watkins (who will also be honored at the library event) and the late astronaut Michael P. Anderson.

There’s also an image in the book of Williamson, standing at a checkstand at the Safeway supermarket where she worked 27 years as a cashier. She believes she was the first black grocery store checker in the city’s history, and working such a visible job that she started in the mid-1960s, Williamson found herself on the front lines of the cultural upheaval occurring during the civil rights movement.

One of her customers waited in a long line with her cart full of groceries. When the woman’s turn finally came, she turned her nose up and scoffed before walking to another checkstand, Williamson said.

“She stood in line all that time, and that’s what she did,” Williamson said. “Just to make a point. It’s hard for you to understand, but I knew what that was.”

Williamson initially applied to work in the store’s bakery, but there were concerns about a black worker handling ingredients with their bare hands, she said.

“People didn’t want you to touch their food and stuff like that, food that was not canned or something like that,” she said.

One story that still brings tears to Williamson’s eyes, 50 years later, is about a man who waited until after their transaction to lean in and make a graphic, racially charged statement to the clerk.

“I said, ‘Thank you, sir,’ and then he said,” Williamson remembered, holding back tears, “ ‘If I had a baby, a black baby, I’d take it out and drown it.’ ”

Williamson’s book tells similar stories of heartbreak, blocked paths and examples of overt racism that faced black residents of Spokane.

There’s a picture of Malbert Cooper, who was buried in an unmarked grave in the 1970s after his death, only to be rediscovered in 2015 as an Army veteran worthy of a headstone.

There’s an image of the Pantages Theater, which lost a lawsuit to a black customer who was forced to sit in the balcony.

And there’s a candid portrait of Sarah Q. Gardner, a hairstylist who set up shop on East Sprague Avenue and ran for Spokane City Council before being stabbed to death in her salon in September 1987, a crime that was never solved.

The pictures were compiled in 1989 for a centennial celebration of Washington state that was displayed at the old downtown Bon Marché department store. A group, called the Spokane Northwest Black Pioneers, was formed to collect the photographs for the display, which now make up the bulk of Williamson’s book.

“All these photos were in her basement, the duplicate photos,” said Jennifer Roseman, one of five of her children, whom Williamson credits with developing the idea for the book. “Because there’s really no one left from the organization. What was going to happen to all that, when she was gone?”

Williamson will join other honorees in the Spokane Hall of Fame who have received the Community Impact Award, which was created by the library foundation to honor those whose contributions don’t fit neatly into other nomination categories, such as arts and letters, science, philanthropy and leadership, said Sarah Bain, the library foundation’s development director.

“Her impact has been across the board,” Bain said of Williamson. “She hasn’t just written a book, or just advocated for African Americans. She really is about education and public service in this community.”

Williamson is a member of the Walk of Fame at Rogers High School, where she graduated in 1950. In 2003, she received the Jefferson Award from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer for distinguished community service.

Flattered by the recognition, Williamson insists the important thing is to continue to keep the stories of Spokane’s black community alive.

“That was my idea, to let people know, we’re here,” Williamson said. “We’ve been here a long time in Spokane.”